Destination Lockdown

by Audrey N. Carpio

Photos courtesy of Audrey N. Carpio

On patience, history, and cassette tapes.

A large part of the job was simply consolidating and coordinating information from different agencies, embassies, and airlines, and instructing people on the steps they needed to take in order to make their way home. Responders made sure that strandees were listed for a rescue flight and that they had all the necessary permits and paperwork. Tourists also turned to us when they ran out of medicine, or money, or places to stay. A few times we received disturbing messages about the rapidly devolving situation on remote islands, where food was running out and a tense, militarized atmosphere stoked fear and paranoia. Foreigners, once received with our renowned hospitality, were starting to feel unwelcomed by the locals, who were increasingly viewing outsiders with suspicion. While we couldn’t always provide solutions, we offered reassurance, or at least a place to lay their frustrations on.

There were some questions, however, which I was at a loss for. “When can I see my fiancé again?” implored several foreigners who were separated from their Filipina partners living in hinterland provinces. A heartsick Swede in Beijing claimed that spending two weeks in a dodgy quarantine facility was nothing compared to the indefinite months he was forced to be apart from his Baguio-based girlfriend. There was an American who was stationed on a ship for months and used to long separations, but not the fact that he was legally barred from returning to his common-law wife and kids in Southern Leyte. A Filipina woman was supposed to leave for the US on a K-1 visa, also known as the fiancé visa, but was instead trapped in the Philippines, the limit on her expensive visa ticking away every time the government announced another lockdown extension.

The queries that stung the most had to do with Filipino citizens who were prevented from returning home right in their own country. They were hapless local travelers who hopped to Boracay for quick family getaway, or maybe they were employees sent on a work trip to check on a regional branch, leaving young children back home. Sometimes they were just students who went to the province on an immersion trip. The abrupt cancellation of flights and strict orders to stay inside turned their short excursions into an endless, unaffordable nightmare. Please just be patient, I must have repeated several times. Help is coming for you. This situation won’t last forever.

We’re now several months into this pandemic, languishing in one of the world’s longest lockdowns. My stint as a customer service rep ended when Metro Manila first moved into GCQ and industries started to open up again. I noticed how I became more clinical as the months wore on, less empathetic, less warm, that I might as well have been a chatbot. Compassion fatigue was real, and it made me profoundly appreciate the real work health frontliners do out there. When I had to get my finger stitched at the ER, I cried not because of the pain, but because I was just grateful there was a doctor attending to my stupid kitchen accident amid all the rising COVID cases. I still wonder about all the people out there who are seeking answers. The hotline remains open, 24/7, ready to receive your queries about quarantine facilities, COVID test results, or whether seniors are allowed out for a walk. A lot of people just want to know when they can get the heck out of here.

︎

The audio cassette Ruth made for Tony in 1972.

The audio cassette Ruth made for Tony in 1972.

Filipinos were once prohibited from traveling internationally, forty-eight years ago. When Martial Law was declared, the Philippines entered an era of darkness reminiscent to the what we are experiencing now, with the closing of media outlets, prohibiting of mass activities, and the suspension of civil rights. Today, ABS-CBN has again been shuttered, while curfews, liquor bans, police checkpoints, localized hard lockdowns, and travel restrictions define the limits of our daily existence in the war against COVID-19, all under the shadow of an anti-terror law that effectively silences activists and protesters during a very contentious period.

The year 1972 was also when my would-be parents were separated by the would-be West Philippine Sea, long-distance sweethearts who were sundered by both choice and circumstance. Ruth was an international student from Vietnam who had just graduated from the University of the Philippines. Her sense of patriotic duty called her back to her home country to teach, leaving behind her boyfriend, Tony, who had yet to finish his law degree. If Tony ever felt inclined to follow Ruth or chase her down in her family home in Sài Gòn, he couldn’t anyway, because of the ban imposed on Filipinos leaving the country.

Like most couples in LDRs during the days before instant messaging, they relied on the olde postal service. Ruth mailed Tony cassettes, recording missives in her Vietnamese-inflected English on a half-blank tape (the other side came with demonstration recordings of random songs like “La Bamba” and “Für Elise”). We’ll never know the exact contents of her contribution to these cassettes, because my mom cringes at the thought of playing them back now.

Tony, who was confined to his own country, had no recourse but to write Ruth back and ask her to return to the Philippines. As a future lawyer, he was probably very persuasive, and even got his father to write her father a letter beseeching her hand in marriage, as was the custom of the times. After several letters and cassette tapes sent over the span of a year, Ruth relented, quit her job, defied her father’s wishes and came back here, not realizing she would be returning to a much bleaker Philippines than the one she had left as a wide-eyed fresh grad.

The year 1972 was also when my would-be parents were separated by the would-be West Philippine Sea, long-distance sweethearts who were sundered by both choice and circumstance. Ruth was an international student from Vietnam who had just graduated from the University of the Philippines. Her sense of patriotic duty called her back to her home country to teach, leaving behind her boyfriend, Tony, who had yet to finish his law degree. If Tony ever felt inclined to follow Ruth or chase her down in her family home in Sài Gòn, he couldn’t anyway, because of the ban imposed on Filipinos leaving the country.

Like most couples in LDRs during the days before instant messaging, they relied on the olde postal service. Ruth mailed Tony cassettes, recording missives in her Vietnamese-inflected English on a half-blank tape (the other side came with demonstration recordings of random songs like “La Bamba” and “Für Elise”). We’ll never know the exact contents of her contribution to these cassettes, because my mom cringes at the thought of playing them back now.

Tony, who was confined to his own country, had no recourse but to write Ruth back and ask her to return to the Philippines. As a future lawyer, he was probably very persuasive, and even got his father to write her father a letter beseeching her hand in marriage, as was the custom of the times. After several letters and cassette tapes sent over the span of a year, Ruth relented, quit her job, defied her father’s wishes and came back here, not realizing she would be returning to a much bleaker Philippines than the one she had left as a wide-eyed fresh grad.

“Please just be patient, I must have repeated several times. Help is coming for you. This situation won’t last forever.”

The ban on foreign travel was lifted only in 1977, along with the curfew. Some 1,500 political prisoners were also released, when the regime realized it wasn’t a good look for the hosting of a world conference on the protection of human rights. My mother gave birth to me in the United States two years later, gifting me with the freedom an American passport promises, just in case things in the Philippines went south. Communism may have been the bogeyman of the Marcos dictatorship, but it was certainly real to my mother, who had just witnessed the dissolution of the Republic of Vietnam, the country of her youth, at the hands of Communist forces in 1975.

“The New Society, if it lives up to the plans and promises, may come to be known in our history as that era when tourism was in flower,” wrote Letty Magsanoc in 1972 in the first issue of Focus Philippines, one of the few officially approved magazines in publication. The journalist would later be known as an icon of democracy, instrumental in overthrowing the regime, but she was partially correct in her early observation of the nascent tourism industry. Tourism as a national policy was institutionalized under Marcos’ New Society, and the ‘70s ushered in a period of frenzied hotel and convention center construction. The first Department of Tourism chief, Jose Aspiras, even used “Martial Law, Filipino Style” as an international selling point, citing that Manila, once known as “Dodge City of the East,” had become a place of peace and order with streets free from crime.

This veneer blew up in their faces, literally, when a bomb exploded at the PICC-held ASTA World Congress, the largest tourism industry event of 1980. While the New Society revealed itself to be an epic sham, tourism itself became an effective tool for national development and a significant driver of economic growth, particularly in the decade since the Tourism Act of 2009 became law. The Philippines hit peak tourism in 2019, with the number of foreign arrivals that year breaking all previous records. It was fun, fun, fun in the Philippines. Then a virus broke out.

![]()

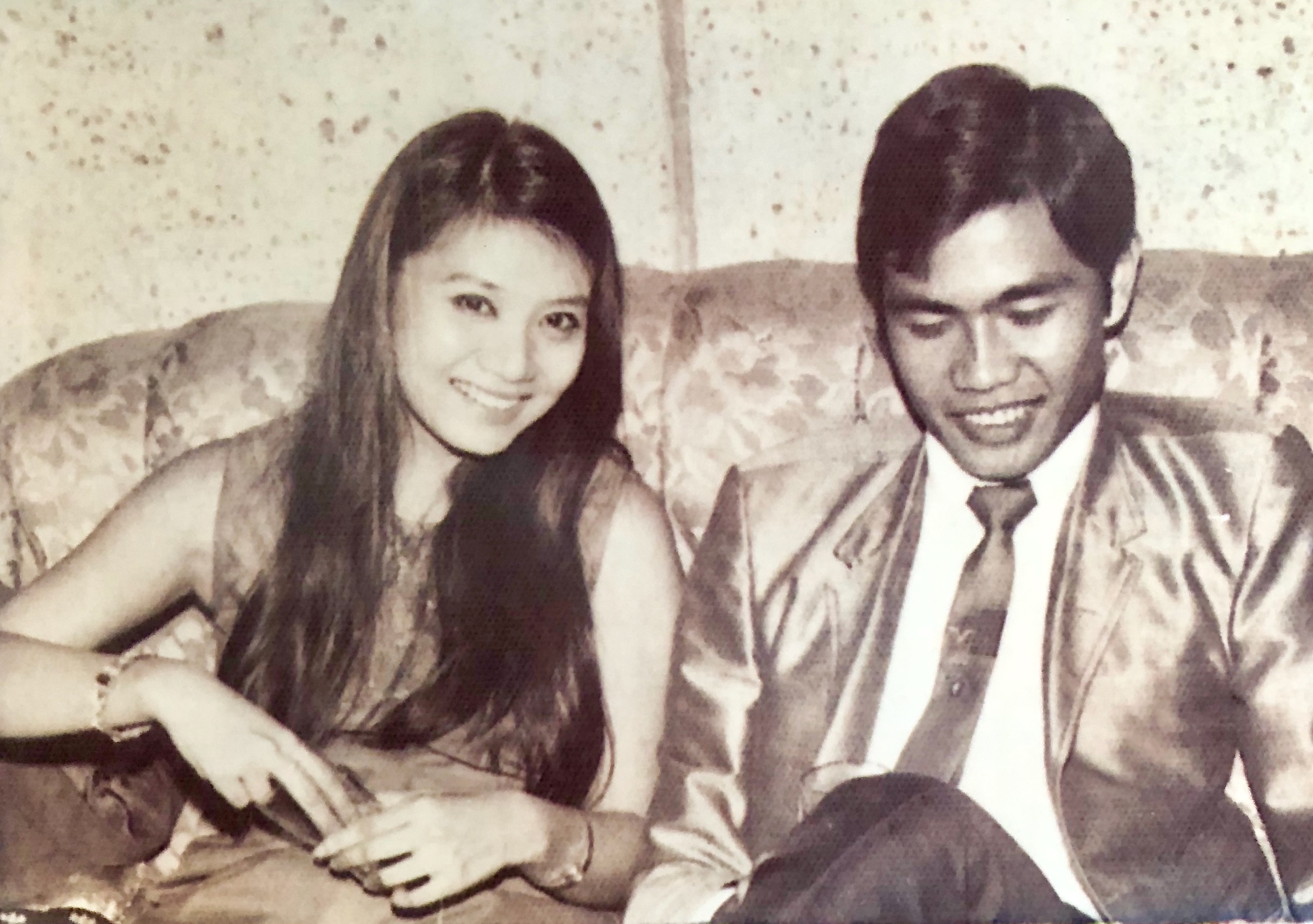

The author’s parents, Ruth and Tony, in 1969.

The author’s parents, Ruth and Tony, in 1969.

The coronavirus was already showing up in several parts of the world by mid-March, but thousands of tourists were still scattered across the archipelago, enjoying the pre-summer weather. Just days before the lockdown, I was on an airline-magazine sponsored trip to El Nido, where I day drank and observed groups of mostly white holidaymakers reveling in their freedom to journey and colonize, neither of us knowing this would be one of our last carefree moments of the year.

The magazine issue never went to print, because the airline had to stop flying. It was a bit disconcerting to find out in one day that the sector you work in, which employs millions of people and affects communities all over the country, was considered non-essential. I understood, of course, that it was travel that brought the virus here, and so it was expected that the shutting down of travel would contain its spread.

Travel, and all of its possibilities and negations, have also brought me to this point, through a mother who crossed borders and a father who couldn’t, to finding escape, as a mere fetus, from future travel limitations and falling nations. If there was ever a perfect time to take advantage of owning a powerful blue passport, the year 2020 obliterated it. So here I am, sheltering, home schooling, anxiety-baking and plantita-ing, working remotely in the travel industry mostly as a writer, but also briefly as a responder to those who didn’t narrowly escape the border closures.

Philippine tourism is expected to rebound, as it always does in the aftermath of crises. The presence of a virus or the absence of a vaccine notwithstanding, people have jobs to get back to and vacations to take. At the moment, the country’s celebrated beaches remain empty, as everyone sits at home waiting for answers, a conclusion, a denouement to this interminable act. I too would like to know: when do we get the heck out of this? ︎

The magazine issue never went to print, because the airline had to stop flying. It was a bit disconcerting to find out in one day that the sector you work in, which employs millions of people and affects communities all over the country, was considered non-essential. I understood, of course, that it was travel that brought the virus here, and so it was expected that the shutting down of travel would contain its spread.

Travel, and all of its possibilities and negations, have also brought me to this point, through a mother who crossed borders and a father who couldn’t, to finding escape, as a mere fetus, from future travel limitations and falling nations. If there was ever a perfect time to take advantage of owning a powerful blue passport, the year 2020 obliterated it. So here I am, sheltering, home schooling, anxiety-baking and plantita-ing, working remotely in the travel industry mostly as a writer, but also briefly as a responder to those who didn’t narrowly escape the border closures.

Philippine tourism is expected to rebound, as it always does in the aftermath of crises. The presence of a virus or the absence of a vaccine notwithstanding, people have jobs to get back to and vacations to take. At the moment, the country’s celebrated beaches remain empty, as everyone sits at home waiting for answers, a conclusion, a denouement to this interminable act. I too would like to know: when do we get the heck out of this? ︎

Audrey Carpio is a writer and former magazine editor.