Out of Print

A Seat at the Table

by Liz YapPhotos courtesy of Bettina Makalintal.

Bettina Makalintal on the potential and promise of Filipino-American food, and the joy of cooking.

But in her last semester of college, she found herself taking a class on the history of Asian food in America with a Filipino professor, with a comprehensive reading list that included Carlos Bulosan’s America Is In The Heart and Doreen Fernandez’s Tikim. The class was revelatory and formative, and it showed Bettina, who’d always had a keen interest in food, that food writing was something she could pursue.

In over two years as a staff writer at Munchies, Bettina has become known for her smart, thoughtful writing and cultural commentary, covering everything from American food media’s oversimplification of global cuisines to delightfully oddball microtrends like frog cakes. Elsewhere on the Internet, she has an Instagram account dedicated to her cooking named @crispyegg420, and lately she’s also been trying her hand at making food videos for TikTok. (It’s hard and it definitely takes more time than she expected, she says.)

When we log on to Zoom for the interview, we compare notes on how recently we each moved to New York—Bettina from Boston in 2018, myself from Manila in 2019—and talk about how disappointing it’s been that so much of our time in this city has been spent in quarantine. It’s a Wednesday night, but it’s been a long week. The day before our interview, a video of a 65-year-old Filipino woman being kicked and attacked while she was on her way to church went viral. I can’t shake off the sight of the doormen closing the building doors instead of intervening, and I find myself wishing I hadn’t seen the video at all. Neither of us have the emotional bandwidth to talk about this even more than we already have, though we eventually work our way up to it. It’s been a long week in a very long year.

Here, Bettina talks about finding her voice as a writer, the trendification of ube, and why she’d rather not refer to any cuisine as “the next big thing.”

The following has been edited for publication.

Liz Yap: Hi Bettina, thank you so much for making time for this interview. I wanted to start by asking when your family moved to the U.S. What was it like growing up Filipino-American?

Bettina Makalintal: We moved to the U.S. in 1997. I was five. I grew up in Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia, in the suburbs. I was the only Filipino person in my school that I knew of until I was probably in the fifth grade. Growing up, I didn’t feel very connected to being Filipino, especially because my parents, as part of this assimilation thing, didn’t make a ton of Filipino food. We didn’t have the Filipino channel on TV, and even if my mom’s best friend is Filipino, webut we didn’t know a lot of other Filipino people. All my friends were Irish. So during my childhood, I didn’t feel super Filipino. It felt like my parents actively distanced us from that, and it was only something I tapped into as more of an adult.

Was there a turning point?

I think it was going to college, being on my own and being able to do stuff away from my parents. And there would be times when I’d miss making lumpia with my mom, and I’d look for those things in Boston where I lived at that time. Being away made me realize I did want to tap into these things about being Filipino and I learned more about it in a way that I didn’t necessarily experience growing up.

I read that you had a class with a professor who was a Filipino food historian in college.

I really lucked out for some reason in college. My last two years, I had two Filipino professors at the same time. I never had a Filipino teacher before so the fact that I had two at the same time was kind of amazing to me. One of the professors was doing a class about public health and the history of American colonialism in the Philippines; the other professor was doing a class on Filipino food. It was very interesting to see these two different perspectives in a way that I never thought about before.

Was that when you started considering a career in food writing?

That was when I realized that food writing was a thing I could do. It was always something I was interested in, I’d watched a lot of food shows and read a lot of food magazines, but I didn’t think about the fact that I could do it until then. For some reason, it felt impenetrable as an industry. But that was when I started to think about it more seriously. I realized that you could approach this from an academic perspective, that there were people who were thinking about food the way I wanted to think about food.

You’ve been with Vice for a little over two years. How did you end up writing for Munchies?

I started writing in 2015. I was working in food service after college and didn’t know what to do with my life. I was working in an ice cream shop where I couldn’t seem to leave it. Every time I tried to quit, I’d just take on a different job there. It was fine for paying my bills but I felt, mentally, I had a lothad lot of extra energy I wanted to use. So I thought I could write about food—, maybe Filipino food—, and that was when I started freelancing. I did that for a few years, mostly writing for The Boston Globe, covering local things in the city. After a few years of that, I started working for a cheese magazine. I was there for a year. I applied to Vice on a whim, and luck worked in my favor and I ended up getting the job.

That’s been really exciting, because I didn’t necessarily think I would ever get a staff writing job or that writing would be my career. I thought I would just do all these other things on the side and write in the meantime. It was really a stroke of luck. Vice has been an interesting opportunity to figure out what my voice is in the food world and find my footing and explore what I feel passionate about covering, and I’ve had a lot of flexibility to figure that out which has been really nice.

What’s the best part of your job?

I do exactly what I’ve wanted to do, which is to learn about food constantly and be really excited about food and translate that for other people. A lot of people don’t get to do the thing they’ve always wanted to do or explore the things they’re interested in, and I sometimes forget that. But it’s nice to remember that this is the path that I wanted and I’m lucky I’ve been able to make it happen.

And the most frustrating?

Writing and being a creative are both inherently frustrating, because you’re always trying to figure out what your personal identity is as a creator. The voice I write in now is different from how I was writing two years ago, I think I write better now than I did then. What’s hard and frustrating is that my writing is hopefully going to be even better a year from now, but I’m always trying to do the most within my current capacity. There’s this little voice telling me I could be a better writer, that it could be better. It’s easy to get swept up in the perfectionism of that. You could just keep editing every piece to death until it meets your standards, believing that if you do five more things, it would be perfect. I think I’m always figuring out when something is good enough and when I can accept that these are the limits of my capabilities right now as a writer.

Bettina Makalintal: We moved to the U.S. in 1997. I was five. I grew up in Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia, in the suburbs. I was the only Filipino person in my school that I knew of until I was probably in the fifth grade. Growing up, I didn’t feel very connected to being Filipino, especially because my parents, as part of this assimilation thing, didn’t make a ton of Filipino food. We didn’t have the Filipino channel on TV, and even if my mom’s best friend is Filipino, webut we didn’t know a lot of other Filipino people. All my friends were Irish. So during my childhood, I didn’t feel super Filipino. It felt like my parents actively distanced us from that, and it was only something I tapped into as more of an adult.

Was there a turning point?

I think it was going to college, being on my own and being able to do stuff away from my parents. And there would be times when I’d miss making lumpia with my mom, and I’d look for those things in Boston where I lived at that time. Being away made me realize I did want to tap into these things about being Filipino and I learned more about it in a way that I didn’t necessarily experience growing up.

I read that you had a class with a professor who was a Filipino food historian in college.

I really lucked out for some reason in college. My last two years, I had two Filipino professors at the same time. I never had a Filipino teacher before so the fact that I had two at the same time was kind of amazing to me. One of the professors was doing a class about public health and the history of American colonialism in the Philippines; the other professor was doing a class on Filipino food. It was very interesting to see these two different perspectives in a way that I never thought about before.

Was that when you started considering a career in food writing?

That was when I realized that food writing was a thing I could do. It was always something I was interested in, I’d watched a lot of food shows and read a lot of food magazines, but I didn’t think about the fact that I could do it until then. For some reason, it felt impenetrable as an industry. But that was when I started to think about it more seriously. I realized that you could approach this from an academic perspective, that there were people who were thinking about food the way I wanted to think about food.

You’ve been with Vice for a little over two years. How did you end up writing for Munchies?

I started writing in 2015. I was working in food service after college and didn’t know what to do with my life. I was working in an ice cream shop where I couldn’t seem to leave it. Every time I tried to quit, I’d just take on a different job there. It was fine for paying my bills but I felt, mentally, I had a lothad lot of extra energy I wanted to use. So I thought I could write about food—, maybe Filipino food—, and that was when I started freelancing. I did that for a few years, mostly writing for The Boston Globe, covering local things in the city. After a few years of that, I started working for a cheese magazine. I was there for a year. I applied to Vice on a whim, and luck worked in my favor and I ended up getting the job.

That’s been really exciting, because I didn’t necessarily think I would ever get a staff writing job or that writing would be my career. I thought I would just do all these other things on the side and write in the meantime. It was really a stroke of luck. Vice has been an interesting opportunity to figure out what my voice is in the food world and find my footing and explore what I feel passionate about covering, and I’ve had a lot of flexibility to figure that out which has been really nice.

What’s the best part of your job?

I do exactly what I’ve wanted to do, which is to learn about food constantly and be really excited about food and translate that for other people. A lot of people don’t get to do the thing they’ve always wanted to do or explore the things they’re interested in, and I sometimes forget that. But it’s nice to remember that this is the path that I wanted and I’m lucky I’ve been able to make it happen.

And the most frustrating?

Writing and being a creative are both inherently frustrating, because you’re always trying to figure out what your personal identity is as a creator. The voice I write in now is different from how I was writing two years ago, I think I write better now than I did then. What’s hard and frustrating is that my writing is hopefully going to be even better a year from now, but I’m always trying to do the most within my current capacity. There’s this little voice telling me I could be a better writer, that it could be better. It’s easy to get swept up in the perfectionism of that. You could just keep editing every piece to death until it meets your standards, believing that if you do five more things, it would be perfect. I think I’m always figuring out when something is good enough and when I can accept that these are the limits of my capabilities right now as a writer.

“Writing and being a creative are both inherently frustrating, because you’re always trying to figure out what your personal identity is as a creator.”

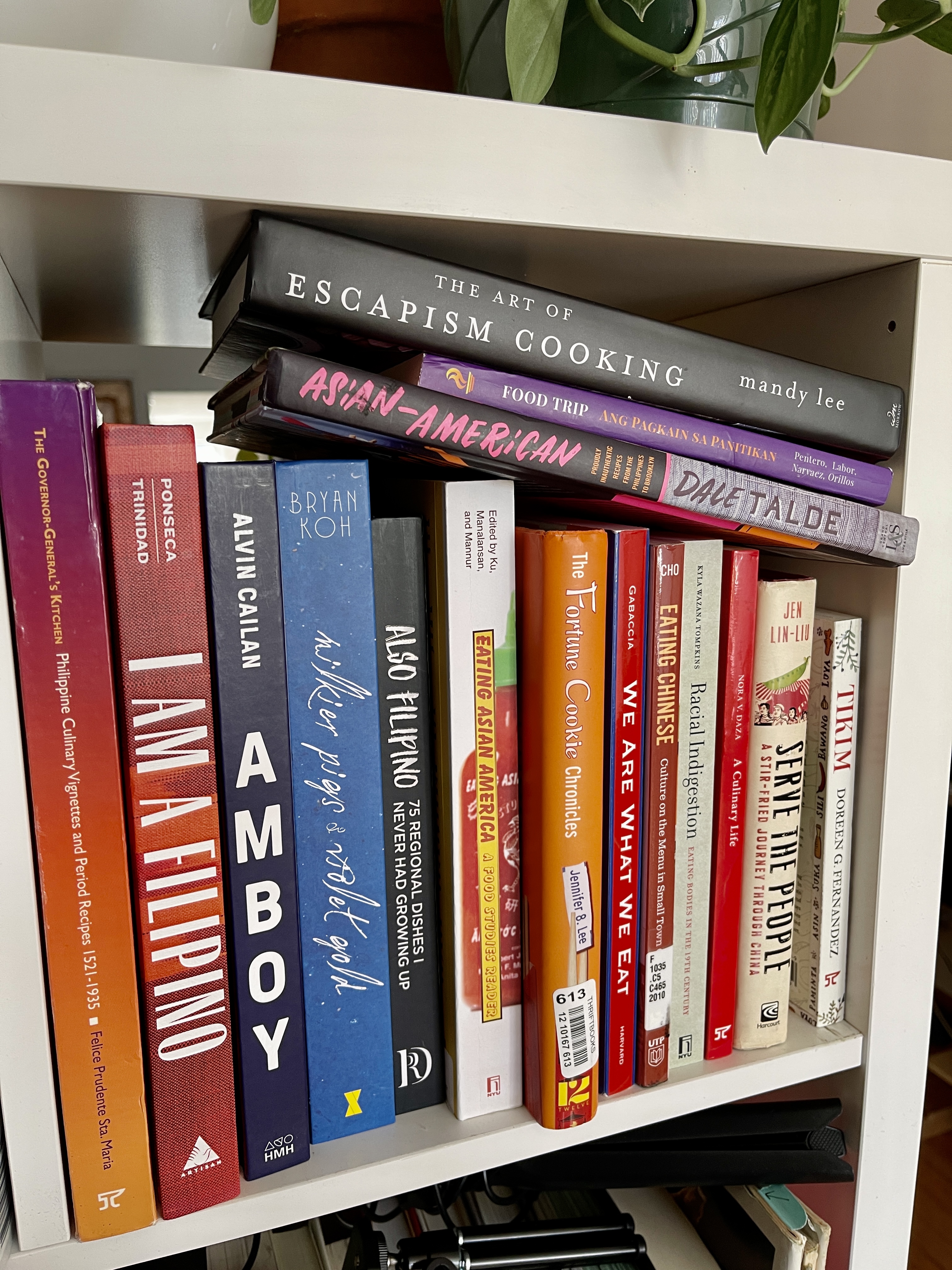

Bettina’s collection of books on food and culture.

When you’re a writer, it’s hard not to be precious about your work, but if you get too caught up in perfectionism, you’ll never publish anything.

That’s the thing that’s hard to accept. When I was a freelancer, I would only write things that I wanted to write. Everything was so precious to me. Now as a staff writer, sometimes there’s something that happens on the news and you have to cover it. Not everything is as deserving of the same amount of energy or thought or perfect writing. But it’s hard for me to be like, “this is fine, just get it out the door” versus “spend two weeks on this thing, make it perfect.”

You’ve written extensively about Filipino food, from Doreen Fernandez’s Tikim to Palm corned beef to how Edam cheese ended up on our Noche Buena tables. I remember reading this article titled “The Color of My Skin Is Sometimes Confused With the Scope of My Talent” about an Indian food writer who worries that writing about Indian food would risk limiting herself to only doing that. Are you ever nervous about getting pigeonholed?

Yeah, I love that piece. I’m constantly afraid of getting pigeonholed. I acknowledge the fact that I launched my career by writing about Filipino food. My first big pieces were about Filipino food, and that was because I sort of knew [it], I’m a Filipino writer, there weren’t a lot of us in the Boston freelance food writing market at that time. I felt like that helped me. I want to write more about Filipino food but at the same time, I think that I hold back from doing certain things, just because I don’t want to only do that.

Instead of just writing about Filipino food or chefs all the time, there’s also power in talking to Filipino chefs for stories about other things. I’ve talked to Filipino chefs for things that are unrelated to Filipino cuisine, and it’s important to help diversify sources. It helps me to write about the Filipino community without feeling like I’m only writing about the Filipino community specifically.

I think that I probably have a bigger fear of getting pigeonholed than I should. If you ask my editor, I don’t think they’d say Bettina writes too much about Filipino food, but it’s this little voice in my head that says, “You just wrote about Filipino food this many months ago so you can’t do it again.” It’s me telling myself that. From the conversations I’ve had with people, every writer, at least in the United States, who’s from a background that isn’t covered a lot in the food world probably feels this way [too]. I’m always in the process of figuring out for myself how much I want to be covering Filipino food at a given moment—if it feels good for me to do that or am I tokenizing it and making it my only value. It’s something I’ve gone back and forth on, and it’s always changing.

Would you ever consider starting a publication dedicated to Filipino cuisine?

I’ve tweeted about this in a joking sense, like if someone wanted to give me a lot of money to back this project, yeah, I would love to. But the way media is structured right now, I don’t see that as a feasible project anytime soon, unfortunately. A lot of people embark on passion projects, but I feel like there’s only so far that passion can take you. You need the financial resources, or else everyone gets burned out and that isn’t good for anyone. But if I could do it in a way that seemed sustainable in the long-term sense, I’d love to have the space for Filipino food stories specifically.

I think there are so many people who would have interesting stories to share and things to say, and so many ways we could broaden what Filipino food looks like in the United States or how we talk about it in the diaspora. And there’s just not a space for us to have those layers of conversation yet.

I feel like many of the articles written about Filipino food in Western publications don’t go deep enough or provide enough context. Ube, for example, gets so much attention just because it’s purple and it’s pretty, or because it’s “Instagrammable,” but it doesn’t go beyond that and I’m not sure they’d be writing about it otherwise.

I’ve had the exact same thought about ube. I haven’t had the courage to write it because it feels like it would upset people. I think ube has taken off because it’s so easily marketable to people. There are a lot of ube desserts that are trendy but don’t even taste that different or special, in my opinion. They’re just purple. And I feel this is the thing with Filipino food. When you’re talking to Western mainstream publications, we always have to introduce it and it’s always the same things repeated, and it’s very rarely going beyond that. “Ube is purple and Filipino food is this thing that you eat with your hands!” You could write about all these other Filipino desserts, or all these other ways Filipinos eat food, or what Filipino food looks like in other parts of the Philippines that aren’t Manila—but that’s the part that we never get to, really.

Right, it’s all very surface-level. Sometimes it seems like ube is becoming the rainbow bagel of desserts.

One thing that I’ve been thinking a lot about too, especially as Filipino food gets attention in various ways, it’s true that once an ingredient or a dish hits a certain level of popularity with communities outside where it came from, you lose control and it’s inevitable. We’re seeing that with gochujang, all these places are using it and Shake Shack is calling it a Korean burger because it has gochujang. We are going to hit that point where people are just going to do what they want with ube and it’s going to have no ties with Filipino culture, and people are going to use it because it’s cool and purple. That is unfortunate but inevitable. That’s something that’s hard to grapple with as you have ties to your cuisine that you love but at the same time, it’s becoming known to people outside the community. I don’t think there’s a solution, but you get to the stage where people are going to do whatever they want with it. Is it worth it for me to get mad about all these ube things? I don’t know.

That’s the thing that’s hard to accept. When I was a freelancer, I would only write things that I wanted to write. Everything was so precious to me. Now as a staff writer, sometimes there’s something that happens on the news and you have to cover it. Not everything is as deserving of the same amount of energy or thought or perfect writing. But it’s hard for me to be like, “this is fine, just get it out the door” versus “spend two weeks on this thing, make it perfect.”

You’ve written extensively about Filipino food, from Doreen Fernandez’s Tikim to Palm corned beef to how Edam cheese ended up on our Noche Buena tables. I remember reading this article titled “The Color of My Skin Is Sometimes Confused With the Scope of My Talent” about an Indian food writer who worries that writing about Indian food would risk limiting herself to only doing that. Are you ever nervous about getting pigeonholed?

Yeah, I love that piece. I’m constantly afraid of getting pigeonholed. I acknowledge the fact that I launched my career by writing about Filipino food. My first big pieces were about Filipino food, and that was because I sort of knew [it], I’m a Filipino writer, there weren’t a lot of us in the Boston freelance food writing market at that time. I felt like that helped me. I want to write more about Filipino food but at the same time, I think that I hold back from doing certain things, just because I don’t want to only do that.

Instead of just writing about Filipino food or chefs all the time, there’s also power in talking to Filipino chefs for stories about other things. I’ve talked to Filipino chefs for things that are unrelated to Filipino cuisine, and it’s important to help diversify sources. It helps me to write about the Filipino community without feeling like I’m only writing about the Filipino community specifically.

I think that I probably have a bigger fear of getting pigeonholed than I should. If you ask my editor, I don’t think they’d say Bettina writes too much about Filipino food, but it’s this little voice in my head that says, “You just wrote about Filipino food this many months ago so you can’t do it again.” It’s me telling myself that. From the conversations I’ve had with people, every writer, at least in the United States, who’s from a background that isn’t covered a lot in the food world probably feels this way [too]. I’m always in the process of figuring out for myself how much I want to be covering Filipino food at a given moment—if it feels good for me to do that or am I tokenizing it and making it my only value. It’s something I’ve gone back and forth on, and it’s always changing.

Would you ever consider starting a publication dedicated to Filipino cuisine?

I’ve tweeted about this in a joking sense, like if someone wanted to give me a lot of money to back this project, yeah, I would love to. But the way media is structured right now, I don’t see that as a feasible project anytime soon, unfortunately. A lot of people embark on passion projects, but I feel like there’s only so far that passion can take you. You need the financial resources, or else everyone gets burned out and that isn’t good for anyone. But if I could do it in a way that seemed sustainable in the long-term sense, I’d love to have the space for Filipino food stories specifically.

I think there are so many people who would have interesting stories to share and things to say, and so many ways we could broaden what Filipino food looks like in the United States or how we talk about it in the diaspora. And there’s just not a space for us to have those layers of conversation yet.

I feel like many of the articles written about Filipino food in Western publications don’t go deep enough or provide enough context. Ube, for example, gets so much attention just because it’s purple and it’s pretty, or because it’s “Instagrammable,” but it doesn’t go beyond that and I’m not sure they’d be writing about it otherwise.

I’ve had the exact same thought about ube. I haven’t had the courage to write it because it feels like it would upset people. I think ube has taken off because it’s so easily marketable to people. There are a lot of ube desserts that are trendy but don’t even taste that different or special, in my opinion. They’re just purple. And I feel this is the thing with Filipino food. When you’re talking to Western mainstream publications, we always have to introduce it and it’s always the same things repeated, and it’s very rarely going beyond that. “Ube is purple and Filipino food is this thing that you eat with your hands!” You could write about all these other Filipino desserts, or all these other ways Filipinos eat food, or what Filipino food looks like in other parts of the Philippines that aren’t Manila—but that’s the part that we never get to, really.

Right, it’s all very surface-level. Sometimes it seems like ube is becoming the rainbow bagel of desserts.

One thing that I’ve been thinking a lot about too, especially as Filipino food gets attention in various ways, it’s true that once an ingredient or a dish hits a certain level of popularity with communities outside where it came from, you lose control and it’s inevitable. We’re seeing that with gochujang, all these places are using it and Shake Shack is calling it a Korean burger because it has gochujang. We are going to hit that point where people are just going to do what they want with ube and it’s going to have no ties with Filipino culture, and people are going to use it because it’s cool and purple. That is unfortunate but inevitable. That’s something that’s hard to grapple with as you have ties to your cuisine that you love but at the same time, it’s becoming known to people outside the community. I don’t think there’s a solution, but you get to the stage where people are going to do whatever they want with it. Is it worth it for me to get mad about all these ube things? I don’t know.

“The fundamental problem I have with the next big thing idea is that it implies at some point, you will stop being the next big thing, right? And it leaves such a tiny bit of room for all of these supposedly up-and-coming cultures because who’s going to be the next big thing after Filipino food then?”

“The fundamental problem I have with the next big thing idea is that it implies at some point, you will stop being the next big thing, right? And it leaves such a tiny bit of room for all of these supposedly up-and-coming cultures because who’s going to be the next big thing after Filipino food then?”

What do you find interesting about Filipino cuisine in America?

The development of specifically Filipino-American food and the fact that the diaspora has its own food culture. What’s really interesting to me is taking the food by Filipinos in the U.S. and the food by Filipinos in the Philippines and seeing how they’re actually different. A lot of times Filipino-American food gets written off as being less authentic—I don’t want to use that word, but it has to be used in this context—or less valid. What’s interesting to me is to accept that food as being totally valid and a separate food culture that was born out of completely different circumstances. If you look at it as a separate thing, then it’s easier to see the value in it and how it’s interesting that people are putting different spins on flavors from the Philippines or dishes we might have grown up with. There’s a lot of promise in the Filipino-American food space and I’m excited to see what people keep doing with it as they get more attention and resources and community around it.

Can you tell us more about what you mean by Filipino-American food culture?

I think that a lot of the new Filipino-American restaurants that are popping up in the U.S. are places where if I take my mom there, she’ll be like, this is different, this is not the way I remember it, because it’s in a different format. Maybe it’s like a longganisa hotdog presented with Filipino toppings (I totally made that dish up but I’m sure someone’s done that), things that don’t feel particularly tied to the way our parents or grandparents made things, but taking those flavors, putting them in a different format, not being afraid to play with how we present Filipino food. Simultaneously, this is happening as the Philippine food scene appears to be really exciting as well. I’ve started following a lot of new restaurants there. People there are putting their own spin on Filipino food in a way that would probably surprise even my own mom. Filipino-American food to me is specifically a response to the entrenched idea my parents’ generation had that Filipino food is only these cheap versions of dishes at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant, playing off those types of dishes and flavors, and doing something new.

Last week, I made the winter greens laing recipe by Melissa Miranda that was published in Bon Appetit. Instead of dried taro leaves, it uses collard greens, Swiss chard, and kale. I loved the idea behind it because taro leaves aren’t easily accessible in the U.S. And it still tasted like laing, it’s just an adaptation for a different audience.

That’s exactly what I mean. I’ve been meaning to make that dish because it sounds really good. I think the diaspora can feel tethered to certain versions of our food because that’s the only way we’ve ever experienced them in the United States, and that can hold certain people back from the idea of change. But all cuisines are always changing, and Filipino cuisine was born out of change and adaptation. I understand why people feel that things can only be a certain version, but we do need to look at the bigger picture. We’ve always had to adapt to the ingredients available to us. That laing is a really good example because a lot of people in the diaspora wouldn’t be able to easily find taro leaves. I would never have been able to find that in suburban Pennsylvania in the ‘90s. People are obviously trying to find workarounds to things and I think it’s not the same cuisine, but a new offshoot of it.

I feel like if I wanted to make things the way my parents made it or my grandparents made it, I could never make it as good, so I might as well try making it a new way.

I think we hold onto the memories of how our families made things, but even if you could make it the exactly same way your mom did, it’s probably not going to feel the same to eat it. It’s not going to feel as good. There’s definitely sentimental value in your parents or grandparents making something that you can’t replicate, because you’re not them and you’re not getting that experience again. It’s freeing in a way, because it makes you realize that you can make your own version of things and it doesn’t matter what you do. You can do things differently. Today I made eggplant adobo, and my parents never made that. We only made adobo with chicken. We also never put coconut milk in adobo, but I made it today, and I put coconut milk in it because I like it that way. It doesn’t detract from how my parents have made it. It’s just me making my own version of it that reminds me of the flavors my parents would use, even if I make these variations.

Have you always cooked a lot, or was it something that became a coping mechanism during the pandemic?

I have typically cooked the majority of my meals, but that changed a bit when I moved to New York. It became more convenient to eat at work, to pick up something on my commute, or to eat at gatherings after work, so I cooked less frequently. I don't know that I consider cooking a coping mechanism during the pandemic, but rather that I've made it my primary hobby. It's become a kind of welcome challenge to cook every day, and doing that has really helped me tap back into my cooking intuition and remember that I find joy in cooking.

What’s your favorite thing to make, and what’s your favorite thing to eat?

I’m a very impulsive cook. I never use recipes and I don’t plan meals out, but generally I love making myself breakfast on the weekend. I like the open-ended possibility that a Saturday morning gives you. I like making breakfast a lot. Always a savory breakfast, I’m not a sweet breakfast person.

My favorite thing to eat, if someone else is cooking it, I love shrimp with the heads on, tossed in some really good sauce. I don’t eat that very often, but it’s one of my favorite foods. You pull the head off and you suck on it and you peel the shrimp apart with your hands.

I’m sure you get this question a lot, but I’m curious about what your experience has been like as a person of color in food media.

I’d say my experience is like what I mentioned initially, the fact that I’m a person of color and specifically Filipino got my foot in the door because I felt that was the untapped market that I saw. I’ve worked with a lot of people of color, and for a long time my editor was also a woman of color and that has been a real benefit to me, and I don’t think everyone gets to experience that.

One thing that has been really nice for me is finding other writers of color in food media, mostly through the Internet. It’s very easy to see other writers as competition, especially given the state of media right now, but having that community online where we’re paying attention to each other’s work and supporting each other virtually and wanting each other to do well has been really nice. The fact that everyone has been so online during covid has helped, because people are a lot more open to talking virtually and interacting more online. I always try to make myself available to other writers for questions or any type of support that I can offer in a professional way.

Do you think that anything changed in the industry after what happened at Bon Appetit last year?

At least for me, I don’t think things have changed a ton as far as my experience since everything that happened last summer. If anything, the one thing that has helped is that the Bon Appetit situation has brought a lot of these topics forward about inequity in food and representation and the unfair way food media has portrayed certain cultures. It’s brought all those topics to a much bigger consciousness, so I do feel like I can write about things like that because the conversation has been broached. A broader range of readers is interested in these questions of how we can make food media more fair and how we can cover topics in a more nuanced way. People are looking for that type of content now in a way that was a little different a year ago.

In one of your articles, you wrote that “the specter of being ‘’the next big thing’ has hung over Filipino food in the United States since at least 2012,” how it’s always up-and-coming and just on the verge of breaking through to a white American audience, and how it’s time to stop framing Filipino food as something on the rise, and to declare it as an integral part of the community that’s here to stay. I found that so interesting because I feel like culturally, because of how long we were colonized, Filipinos really yearn for white validation and that stamp of approval.

In a sense, it almost feels soothing for us to tell ourselves that. Every time there’s an article that says Filipino food is the next big thing, my mom would send it to me and be like, this is so exciting. It’s nice to be able to have that recognition. But at this point, I feel like we just keep saying it and people haven’t stopped to realize it’s big already. We don’t need to keep pretending like we’re predicting when in a lot of places, it did take off. It feels nice to be like, oh, people are paying attention to us, we’re “up-and-coming”, but at the same time we’re also just here and don’t need to keep pretending like we’re heralding something new.

The fundamental problem I have with the next big thing idea is that it implies at some point, you will stop being the next big thing, right? And it leaves such a tiny bit of room for all of these supposedly up-and-coming cultures because who’s going to be the next big thing after Filipino food then? It doesn’t give any culture staying power or doesn’t imply it, it just suggests everyone needs to be in competition for this cool thing that’s getting attention right now. I think that’s a mentality that isn’t good for Asian cuisine especially in the United States—the idea that we need to be competing for the most attention or most success, when the reality is that everything can just coexist.

And it doesn’t have to be trendy to be successful.

I think the trendification of Filipino food has also resulted in a very specific image of what Filipino food is, at least in the United States, and that image is a bit inaccurate. We’ve come to see Filipino food as these ube desserts that are perfect for Instagram or these extremely elaborate kamayan feasts that have been portrayed as like, “this is how Filipino people eat.” Only once in my life has my mom put up banana leaves and a giant spread on our table for breakfast. That trendification has created a very particular type of Filipino cuisine that isn’t the reality of how most Filipino people are actually eating at home.

The development of specifically Filipino-American food and the fact that the diaspora has its own food culture. What’s really interesting to me is taking the food by Filipinos in the U.S. and the food by Filipinos in the Philippines and seeing how they’re actually different. A lot of times Filipino-American food gets written off as being less authentic—I don’t want to use that word, but it has to be used in this context—or less valid. What’s interesting to me is to accept that food as being totally valid and a separate food culture that was born out of completely different circumstances. If you look at it as a separate thing, then it’s easier to see the value in it and how it’s interesting that people are putting different spins on flavors from the Philippines or dishes we might have grown up with. There’s a lot of promise in the Filipino-American food space and I’m excited to see what people keep doing with it as they get more attention and resources and community around it.

Can you tell us more about what you mean by Filipino-American food culture?

I think that a lot of the new Filipino-American restaurants that are popping up in the U.S. are places where if I take my mom there, she’ll be like, this is different, this is not the way I remember it, because it’s in a different format. Maybe it’s like a longganisa hotdog presented with Filipino toppings (I totally made that dish up but I’m sure someone’s done that), things that don’t feel particularly tied to the way our parents or grandparents made things, but taking those flavors, putting them in a different format, not being afraid to play with how we present Filipino food. Simultaneously, this is happening as the Philippine food scene appears to be really exciting as well. I’ve started following a lot of new restaurants there. People there are putting their own spin on Filipino food in a way that would probably surprise even my own mom. Filipino-American food to me is specifically a response to the entrenched idea my parents’ generation had that Filipino food is only these cheap versions of dishes at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant, playing off those types of dishes and flavors, and doing something new.

Last week, I made the winter greens laing recipe by Melissa Miranda that was published in Bon Appetit. Instead of dried taro leaves, it uses collard greens, Swiss chard, and kale. I loved the idea behind it because taro leaves aren’t easily accessible in the U.S. And it still tasted like laing, it’s just an adaptation for a different audience.

That’s exactly what I mean. I’ve been meaning to make that dish because it sounds really good. I think the diaspora can feel tethered to certain versions of our food because that’s the only way we’ve ever experienced them in the United States, and that can hold certain people back from the idea of change. But all cuisines are always changing, and Filipino cuisine was born out of change and adaptation. I understand why people feel that things can only be a certain version, but we do need to look at the bigger picture. We’ve always had to adapt to the ingredients available to us. That laing is a really good example because a lot of people in the diaspora wouldn’t be able to easily find taro leaves. I would never have been able to find that in suburban Pennsylvania in the ‘90s. People are obviously trying to find workarounds to things and I think it’s not the same cuisine, but a new offshoot of it.

I feel like if I wanted to make things the way my parents made it or my grandparents made it, I could never make it as good, so I might as well try making it a new way.

I think we hold onto the memories of how our families made things, but even if you could make it the exactly same way your mom did, it’s probably not going to feel the same to eat it. It’s not going to feel as good. There’s definitely sentimental value in your parents or grandparents making something that you can’t replicate, because you’re not them and you’re not getting that experience again. It’s freeing in a way, because it makes you realize that you can make your own version of things and it doesn’t matter what you do. You can do things differently. Today I made eggplant adobo, and my parents never made that. We only made adobo with chicken. We also never put coconut milk in adobo, but I made it today, and I put coconut milk in it because I like it that way. It doesn’t detract from how my parents have made it. It’s just me making my own version of it that reminds me of the flavors my parents would use, even if I make these variations.

Have you always cooked a lot, or was it something that became a coping mechanism during the pandemic?

I have typically cooked the majority of my meals, but that changed a bit when I moved to New York. It became more convenient to eat at work, to pick up something on my commute, or to eat at gatherings after work, so I cooked less frequently. I don't know that I consider cooking a coping mechanism during the pandemic, but rather that I've made it my primary hobby. It's become a kind of welcome challenge to cook every day, and doing that has really helped me tap back into my cooking intuition and remember that I find joy in cooking.

What’s your favorite thing to make, and what’s your favorite thing to eat?

I’m a very impulsive cook. I never use recipes and I don’t plan meals out, but generally I love making myself breakfast on the weekend. I like the open-ended possibility that a Saturday morning gives you. I like making breakfast a lot. Always a savory breakfast, I’m not a sweet breakfast person.

My favorite thing to eat, if someone else is cooking it, I love shrimp with the heads on, tossed in some really good sauce. I don’t eat that very often, but it’s one of my favorite foods. You pull the head off and you suck on it and you peel the shrimp apart with your hands.

I’m sure you get this question a lot, but I’m curious about what your experience has been like as a person of color in food media.

I’d say my experience is like what I mentioned initially, the fact that I’m a person of color and specifically Filipino got my foot in the door because I felt that was the untapped market that I saw. I’ve worked with a lot of people of color, and for a long time my editor was also a woman of color and that has been a real benefit to me, and I don’t think everyone gets to experience that.

One thing that has been really nice for me is finding other writers of color in food media, mostly through the Internet. It’s very easy to see other writers as competition, especially given the state of media right now, but having that community online where we’re paying attention to each other’s work and supporting each other virtually and wanting each other to do well has been really nice. The fact that everyone has been so online during covid has helped, because people are a lot more open to talking virtually and interacting more online. I always try to make myself available to other writers for questions or any type of support that I can offer in a professional way.

Do you think that anything changed in the industry after what happened at Bon Appetit last year?

At least for me, I don’t think things have changed a ton as far as my experience since everything that happened last summer. If anything, the one thing that has helped is that the Bon Appetit situation has brought a lot of these topics forward about inequity in food and representation and the unfair way food media has portrayed certain cultures. It’s brought all those topics to a much bigger consciousness, so I do feel like I can write about things like that because the conversation has been broached. A broader range of readers is interested in these questions of how we can make food media more fair and how we can cover topics in a more nuanced way. People are looking for that type of content now in a way that was a little different a year ago.

In one of your articles, you wrote that “the specter of being ‘’the next big thing’ has hung over Filipino food in the United States since at least 2012,” how it’s always up-and-coming and just on the verge of breaking through to a white American audience, and how it’s time to stop framing Filipino food as something on the rise, and to declare it as an integral part of the community that’s here to stay. I found that so interesting because I feel like culturally, because of how long we were colonized, Filipinos really yearn for white validation and that stamp of approval.

In a sense, it almost feels soothing for us to tell ourselves that. Every time there’s an article that says Filipino food is the next big thing, my mom would send it to me and be like, this is so exciting. It’s nice to be able to have that recognition. But at this point, I feel like we just keep saying it and people haven’t stopped to realize it’s big already. We don’t need to keep pretending like we’re predicting when in a lot of places, it did take off. It feels nice to be like, oh, people are paying attention to us, we’re “up-and-coming”, but at the same time we’re also just here and don’t need to keep pretending like we’re heralding something new.

The fundamental problem I have with the next big thing idea is that it implies at some point, you will stop being the next big thing, right? And it leaves such a tiny bit of room for all of these supposedly up-and-coming cultures because who’s going to be the next big thing after Filipino food then? It doesn’t give any culture staying power or doesn’t imply it, it just suggests everyone needs to be in competition for this cool thing that’s getting attention right now. I think that’s a mentality that isn’t good for Asian cuisine especially in the United States—the idea that we need to be competing for the most attention or most success, when the reality is that everything can just coexist.

And it doesn’t have to be trendy to be successful.

I think the trendification of Filipino food has also resulted in a very specific image of what Filipino food is, at least in the United States, and that image is a bit inaccurate. We’ve come to see Filipino food as these ube desserts that are perfect for Instagram or these extremely elaborate kamayan feasts that have been portrayed as like, “this is how Filipino people eat.” Only once in my life has my mom put up banana leaves and a giant spread on our table for breakfast. That trendification has created a very particular type of Filipino cuisine that isn’t the reality of how most Filipino people are actually eating at home.

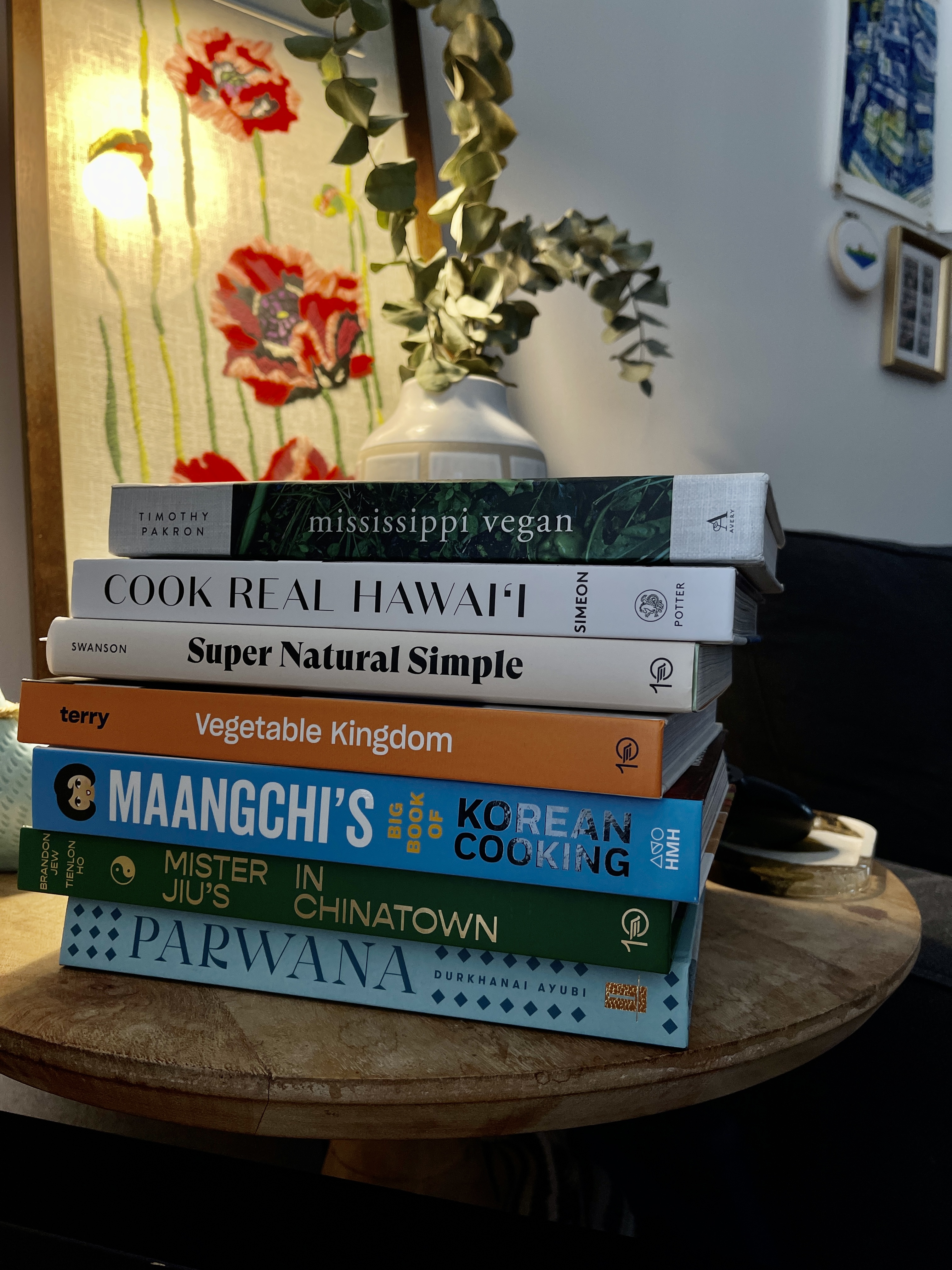

Bettina’s eggplant adobo and vegetable kare-kare.

I don’t know if you’ve seen this on Instagram, but it became a weird trend in the Philippines too. They call them boodle fights now, and there are caterers who specialize in doing that whole setup.

Do you think that was influenced by kamayan feasts being a trend in the United States?

Oh wow, I never thought of it that way.

I talked to someone about this for a story a long time ago and they were telling me that the trends do go both ways, that Filipino chefs are looking at what Filipino-Americans are doing and there is this sort of exchange happening even if they aren’t thinking about that. I haven’t done any more research on that, but that seems interesting. I wonder how the timeline matches up.

I do think that’s possible, that seeing kamayan feasts in the U.S. validated that practice for people back home.

I feel like the way kamayan has been accepted in the United States has proven that even white people who don’t know Filipino food want to eat Filipino food with their hands, and it’s an experience. It’s shown that it can actually be popular and successful.

It’s also been interesting to see Filipino food trends that break into my consciousness here. Like the sushi bake, that blew up so much in the Philippines and then it blew up here. Bon Appetit wrote about it and mentioned its popularity in the Philippines. It’s so wild that this trend is directly traceable to the Filipino social media sphere during the pandemic. I’m thankful that Instagram has allowed me to be in touch with the food scene in the Philippines even though I can’t physically be.

You recently wrote about the Atlanta shooting and how statements like “love our people like you love our food” are problematic, and I wanted to hear more from you about that.

I think the crux of that piece was not necessarily that that slogan was problematic, but the American tendency to see immigrant value based on cultural products and labor is fundamentally problematic. It’s fundamentally bad that we only see people’s worth based on how hard they work or what they provide. Nobody should have to justify their right to exist, because they work so hard or you like the food they make. Everyone’s life has value and we don’t need to constantly prove why we shouldn’t be attacked on the streets or killed when we’re not expecting it. I don’t think anyone is more worthy of their right to be alive based on how hard they’re working. That argument implies that people who don’t do as much aren’t as valuable and that’s a terrible way to look at human life. I think it benefits us all to see people as more than just their work or contributions to the larger culture.

I personally find it ridiculous that we have to validate our right to just walk down the street. Nobody should have to live in fear of walking outside or existing publicly, or have to qualify that for various reasons. It’s ridiculous that we have to prove that people are worth not being attacked in public, that’s the reality, but every time I think about the fact that actually what we’re asking is so fundamental and so basic, it just makes me feel terrible.

What kind of world do we live in that this is something that we have to ask for?

And that people excuse it in various ways or try to make justifications for why things happen. Nobody’s 65-year-old grandmother should be attacked in broad daylight and no one should go to work and be afraid that they’ll get murdered. I hate that this is the reality that so many people are facing right now. And you know, a lot of people in the United States have faced this for a really long time. But the fact that we have to ask for people’s basic human lives to be respected is absurd.

I find it upsetting too, because a lot of immigrants come here thinking it’ll be safer or it’ll be a better life, and this is what the reality we have to deal with.

I’ve thought about that a lot, too. I tweeted something to that effect, and someone pointed out that in a lot of other countries, this still is the better life. But if I think about my parents for example, I don’t think that racialized violence is something that they had to deal with in the Philippines. There wasn’t someone yelling, “You don’t belong here, go back to Asia!” That’s been really jarring to me recently, the fact that when my parents came here, I don’t think they even thought this would be happening or that it would be a concern. That suddenly being in public is a threat. It is heartbreaking to me to think about that.

It’s just been a sad week. I feel every week now, there’s always something happening and it’s mentally exhausting for everyone to constantly keep up with grief on so many levels, like we’ve been doing for the past year.

When you write about things like this, is it ever cathartic for you? Is it a way of processing your emotions or feelings?

I don’t know. I don’t personally think so, but maybe I’m just not acknowledging that it is. It doesn’t feel that way necessarily. It feels better to get thoughts out of my head. I guess that’s processing.

I’m thinking that for a lot of people who read your work, it’s cathartic for them to see their similar thoughts or feelings written out in a way that maybe they’re unable to articulate, and you’re able to do that for them.

I sometimes feel like I’m the only person who feels a certain way, even if I know that’s fundamentally not true. When I write something and people tell me it resonates with them, it means so much to me because I always feel like I’m the lone person shouting into the void. It’s meaningful when it turns out that other people feel the same and maybe just hadn’t thought of a way to articulate it. It’s something I am continually surprised by. ︎

Do you think that was influenced by kamayan feasts being a trend in the United States?

Oh wow, I never thought of it that way.

I talked to someone about this for a story a long time ago and they were telling me that the trends do go both ways, that Filipino chefs are looking at what Filipino-Americans are doing and there is this sort of exchange happening even if they aren’t thinking about that. I haven’t done any more research on that, but that seems interesting. I wonder how the timeline matches up.

I do think that’s possible, that seeing kamayan feasts in the U.S. validated that practice for people back home.

I feel like the way kamayan has been accepted in the United States has proven that even white people who don’t know Filipino food want to eat Filipino food with their hands, and it’s an experience. It’s shown that it can actually be popular and successful.

It’s also been interesting to see Filipino food trends that break into my consciousness here. Like the sushi bake, that blew up so much in the Philippines and then it blew up here. Bon Appetit wrote about it and mentioned its popularity in the Philippines. It’s so wild that this trend is directly traceable to the Filipino social media sphere during the pandemic. I’m thankful that Instagram has allowed me to be in touch with the food scene in the Philippines even though I can’t physically be.

You recently wrote about the Atlanta shooting and how statements like “love our people like you love our food” are problematic, and I wanted to hear more from you about that.

I think the crux of that piece was not necessarily that that slogan was problematic, but the American tendency to see immigrant value based on cultural products and labor is fundamentally problematic. It’s fundamentally bad that we only see people’s worth based on how hard they work or what they provide. Nobody should have to justify their right to exist, because they work so hard or you like the food they make. Everyone’s life has value and we don’t need to constantly prove why we shouldn’t be attacked on the streets or killed when we’re not expecting it. I don’t think anyone is more worthy of their right to be alive based on how hard they’re working. That argument implies that people who don’t do as much aren’t as valuable and that’s a terrible way to look at human life. I think it benefits us all to see people as more than just their work or contributions to the larger culture.

I personally find it ridiculous that we have to validate our right to just walk down the street. Nobody should have to live in fear of walking outside or existing publicly, or have to qualify that for various reasons. It’s ridiculous that we have to prove that people are worth not being attacked in public, that’s the reality, but every time I think about the fact that actually what we’re asking is so fundamental and so basic, it just makes me feel terrible.

What kind of world do we live in that this is something that we have to ask for?

And that people excuse it in various ways or try to make justifications for why things happen. Nobody’s 65-year-old grandmother should be attacked in broad daylight and no one should go to work and be afraid that they’ll get murdered. I hate that this is the reality that so many people are facing right now. And you know, a lot of people in the United States have faced this for a really long time. But the fact that we have to ask for people’s basic human lives to be respected is absurd.

I find it upsetting too, because a lot of immigrants come here thinking it’ll be safer or it’ll be a better life, and this is what the reality we have to deal with.

I’ve thought about that a lot, too. I tweeted something to that effect, and someone pointed out that in a lot of other countries, this still is the better life. But if I think about my parents for example, I don’t think that racialized violence is something that they had to deal with in the Philippines. There wasn’t someone yelling, “You don’t belong here, go back to Asia!” That’s been really jarring to me recently, the fact that when my parents came here, I don’t think they even thought this would be happening or that it would be a concern. That suddenly being in public is a threat. It is heartbreaking to me to think about that.

It’s just been a sad week. I feel every week now, there’s always something happening and it’s mentally exhausting for everyone to constantly keep up with grief on so many levels, like we’ve been doing for the past year.

When you write about things like this, is it ever cathartic for you? Is it a way of processing your emotions or feelings?

I don’t know. I don’t personally think so, but maybe I’m just not acknowledging that it is. It doesn’t feel that way necessarily. It feels better to get thoughts out of my head. I guess that’s processing.

I’m thinking that for a lot of people who read your work, it’s cathartic for them to see their similar thoughts or feelings written out in a way that maybe they’re unable to articulate, and you’re able to do that for them.

I sometimes feel like I’m the only person who feels a certain way, even if I know that’s fundamentally not true. When I write something and people tell me it resonates with them, it means so much to me because I always feel like I’m the lone person shouting into the void. It’s meaningful when it turns out that other people feel the same and maybe just hadn’t thought of a way to articulate it. It’s something I am continually surprised by. ︎

Liz Yap is a former magazine editor, writer, and brand strategist..