Out of Print

Derek Tumala Can Do Everything

by Toni Potenciano

Portraits by Judd Figuerres

A 10-day trek through Nepal, a rave in a museum, and a solar powered sun are just some of the things that make up the universe of Derek Tumala, a visual artist who defies categorization.

“It was altitude sickness,” he says, or what happens when the body doesn’t adjust to the lower levels of oxygen in higher altitudes. “Ginigising ko ‘yung guide ko and he was like ‘you’re fine.’ I told him, ‘I can’t breathe!’ and he just kept saying ‘You’re fine. You’re not dying.’”

The year was 2012. Derek was 26 then. “I was going through a lot,” he tells me the morning of our interview. “I was not really practicing, not doing exhibitions. I was trying to figure out what I wanted, and that’s normal with art practices.”

So he took to India and Sri Lanka to join meditation camps and hike mountains for answers. Annapurna wasn’t part of the original plan. “I just met this Filipino family in Kathmandu at a meditation camp, and they helped me arrange the trip.” Derek thought of going to Mt. Everest, but they dissuaded him. “It’s just all ice and an ego thing,” recalling their advice. Annapurna on the other hand offered breathtaking landscapes and close encounters with the region’s culture and biodiversity.

“It changed my entire being,” he tells me. Derek hiked five to seven hours a day, rushing to the next stop before dark lest they risk getting snowblind. Then he had to wake up before dawn to do it all over again. “It challenged my physical and mental capacity. You just had to keep hiking to reach the next guesthouse, the next place. I asked myself, why am I doing this?”

We sit on the low couches of Club Kino, an experimental space and gallery that Derek manages as one of its partners. The past few months have been exceptionally busy for Derek in the run-up to the 2024 edition of Art Fair, the biggest art event in the city. His public installation entitled “A warm colored liquid”—a six meter tall globe made from steel, recycled abaca paper dyed with turmeric, and solar-powered LED lights—was one of the fair’s biggest highlights. In an article, it was called Derek’s “biggest and most ambitious work yet.”

The massive orange sculpture sits at the center of the fountains of Ayala Tower One. At night, the sculpture lights up, illuminating the faces of office workers and passersby with a warm orange glow. A few meters away are the solar panels that power the work. Depending on the amount of sun that day, Derek’s sun can stay lit for more than five hours. This isn’t necessarily always the case.

“Mayroon time that [the sculpture] was only lit for a period of time, and Ayala asked why. Bakit 8 o’ clock lang, ganun. It was cloudy during that period, so it didn’t transmit enough power to power it for more than five hours, and it’s part of the work,” Derek says.

For Derek, his artworks are never finished. “Art should start a conversation,” More than spectacle, the work is a larger question about how we view sustainable development in the face of the climate crisis. For Derek, art can be a form of public service. Shedding light on things we ought to think about and reimagine.

Though Art Fair had concluded, Derek kept working. His sculpture at the Ayala Triangle Gardens was up til the end of March. He recently debuted “winter high through the veins in search of hot weather” a video and exhibit he created with artist Mano Gonzales at Edoweird. The next day, he was scheduled for a talk at ALT Philippines. Afterward, Derek headed to La Union to lay the groundwork for another project. I ask: How does someone as busy as you relax?

He laughs a long laugh before answering. “I travel. For long periods, if possible. I love nature. Beach. Cities, sometimes. I like traveling, I like moving around. Walking, hiking.”

And that’s how we arrived at Annapurna. Amongst the rocks, ice, and moonlight, Derek found answers. “I learned endurance,” he says. But not all of his epiphanies were personal. When you’re pushed to your limits and everything is stripped away, the emptiness can give way to the sublime.

“Seeing all that nature… I thought about what nature is about, and how it’s not really separated from who I am,” he ponders. He realized then that everything is connected and that we’re all part of a bigger chain of existence. “An ecological way of thinking,” Derek says.

In the years since, Derek has become a prolific and multi-awarded visual artist, known for his multimedia works that present new systems of thought through the intersections of art and science. His CV includes exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design Philippines (MCAD), the Cultural Center of the Philippines, and Art Basel Hong Kong. He’s taken up residencies in Austria, New York, and the Jesuit-run Manila Observatory. In 2023, his work called “The State of Being Wild” (paper mache, archival photographs, film) with the International Rice Research Institute was exhibited at the Yogyakarta Biennale. He was named one of the ArtReview Magazine’s Future Greats 2024. He’s a convener of various art collectives and communities, and now he has his own space in the form of Kino, where Derek can explore and show his work freely.

“Artmaking is so scary, because you’re always trying to present a new idea,” Derek says. “Because I always think about security, and to do [art full-time] is to let go of that. You always feel like the last project is your best and you only get known for that. You can fail, but you just have to get back to it.”

Though Derek is an advertising graduate, he didn’t go into advertising. “It wasn’t for me,” he says. So he went into fashion, working as an in-house creative for Lee, an international denim brand. “The environment wasn’t really corporate. I could go any time I wanted, wear what I want,” Derek recalls.

His favorite memory of the time was the brand’s involvement with Pulp Summer Slam, one of Asia’s longest-running rock and metal festivals held in Amoranto Stadium. “I covered that! I was so inspired by that,” he says with a laugh. “The punk scene, being punk, the underground. These are my inspirations.”

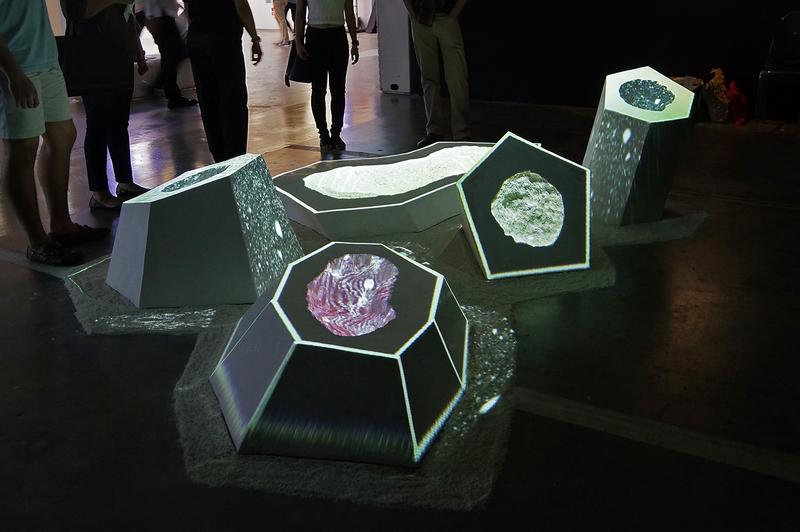

This spirit animates Derek’s art practice. A confessed child of the internet, he gathers inspiration and knowledge from wherever he can search. Derek made lit sculptures with dichroic film, a digital garden that reflects real-time weather, and a video-mapping installation of sacred geometry over sculptures. He’s incorporated live performances, raves, and film into his research-based projects. While a lot of his work can be considered “new media,” Derek refuses to fall into traditional categorization.

“I can’t be a full-time new media artist, and I don’t want to,” he says. “It’s limiting. I think the word ‘new media’ in itself is kind of ambiguous because new media indicates time. What is [considered as] new media today, what is new media in the past... It’s a whole spectrum.”

Derek’s works may seem disparate at first, but closer inspection reveals the laws of gravity that govern them. They constellate around the interconnectedness of things: science and art; man and nature; weather and colonization; progress and the climate crisis. Derek is an interpreter of the world – the way it works, the things that make it cruel and impossible to live in, but he also presents an alternative. A glimpse into what might constitute a better world.

Director Judd Figuerres describes Derek’s work as sensitive. “Always serving a greater purpose,” he writes over email. “He comes from a place of pure intention: his art exists because it aims to untangle these social impediments that we experience and often ignore every day.”

“[Derek] is a voyager,” writes Erwin, writer and frequent collaborator of Derek. “And he's got big ideas—cosmological in scope and widescreen in scale—which is a rare quality in Philippine culture, not just the arts.”

“Even rarer is the wit inherent in the work. With each of Derek's exhibits there's an element of fun that doesn't require wall text to impart. It's built-in.”

His favorite memory of the time was the brand’s involvement with Pulp Summer Slam, one of Asia’s longest-running rock and metal festivals held in Amoranto Stadium. “I covered that! I was so inspired by that,” he says with a laugh. “The punk scene, being punk, the underground. These are my inspirations.”

This spirit animates Derek’s art practice. A confessed child of the internet, he gathers inspiration and knowledge from wherever he can search. Derek made lit sculptures with dichroic film, a digital garden that reflects real-time weather, and a video-mapping installation of sacred geometry over sculptures. He’s incorporated live performances, raves, and film into his research-based projects. While a lot of his work can be considered “new media,” Derek refuses to fall into traditional categorization.

“I can’t be a full-time new media artist, and I don’t want to,” he says. “It’s limiting. I think the word ‘new media’ in itself is kind of ambiguous because new media indicates time. What is [considered as] new media today, what is new media in the past... It’s a whole spectrum.”

Derek’s works may seem disparate at first, but closer inspection reveals the laws of gravity that govern them. They constellate around the interconnectedness of things: science and art; man and nature; weather and colonization; progress and the climate crisis. Derek is an interpreter of the world – the way it works, the things that make it cruel and impossible to live in, but he also presents an alternative. A glimpse into what might constitute a better world.

Director Judd Figuerres describes Derek’s work as sensitive. “Always serving a greater purpose,” he writes over email. “He comes from a place of pure intention: his art exists because it aims to untangle these social impediments that we experience and often ignore every day.”

“[Derek] is a voyager,” writes Erwin, writer and frequent collaborator of Derek. “And he's got big ideas—cosmological in scope and widescreen in scale—which is a rare quality in Philippine culture, not just the arts.”

“Even rarer is the wit inherent in the work. With each of Derek's exhibits there's an element of fun that doesn't require wall text to impart. It's built-in.”

“Because I always think about security, and to do [art full-time] is to let go of that. You always feel like the last project is your best and you only get known for that.”

With Club Kino’s inaugural exhibit “In The Shadows of This New World,” Derek invited artists to reflect on how we might imagine a better world through punk sensibilities. It featured works from veterans in the contemporary art scene, many of whom are Derek’s friends. But the show also had a performance component to it – a live reading from Erwin and DJ sets by Auspicious Family, Big Hat Gang, and Major Chie. “[At Kino], we are trying to challenge art exhibition making,” Derek tells me.

“All around us are these commercial galleries. We really wanted Kino to be different,” he says. Beanbags are strewn across the film projection room. Outside, the mahogany walls hold a six-channel video work by Christina Lopez and a mixed media assemblage by Margaux Blas. Nothing is out of place in Kino.

But experimental spaces like these are few and far between, simply because such works are not always considered sellable. “What I’ve observed—especially in Asia—is that new media is always presented in alternative spaces compared to other countries. Galleries in Asia are often for selling [artworks],” Derek says. Most of these works are usually paintings.

“What will it take for more experimental and conceptual works to have a broader base of support, besides money?” I ask.

Money is one thing, Derek says, but it’s not everything. “It’s really about creating ecosystems of support,” Derek says. “Not just us artists. It’s supposed to be curators, gallerists, programmers, and other disciplines that could be interested [in new media].”

For Derek, art evolves through different mediums, people, and places. More inclusive spaces and programming for artists to show their works. “We don’t have biennales here, we don’t have art week. We don’t have different forms of art programming, we only have an Art Fair and gallery shows. That’s not enough,” Derek says.

It requires a strong community. “We need more people to have different angles,” Derek says. Different takes on art and what it can be. “Kasi if kami lang, if it’s just us, it’s just one angle, I don’t think that’s viable to everyone kung ito lang ang meron.”

“All around us are these commercial galleries. We really wanted Kino to be different,” he says. Beanbags are strewn across the film projection room. Outside, the mahogany walls hold a six-channel video work by Christina Lopez and a mixed media assemblage by Margaux Blas. Nothing is out of place in Kino.

But experimental spaces like these are few and far between, simply because such works are not always considered sellable. “What I’ve observed—especially in Asia—is that new media is always presented in alternative spaces compared to other countries. Galleries in Asia are often for selling [artworks],” Derek says. Most of these works are usually paintings.

“What will it take for more experimental and conceptual works to have a broader base of support, besides money?” I ask.

Money is one thing, Derek says, but it’s not everything. “It’s really about creating ecosystems of support,” Derek says. “Not just us artists. It’s supposed to be curators, gallerists, programmers, and other disciplines that could be interested [in new media].”

For Derek, art evolves through different mediums, people, and places. More inclusive spaces and programming for artists to show their works. “We don’t have biennales here, we don’t have art week. We don’t have different forms of art programming, we only have an Art Fair and gallery shows. That’s not enough,” Derek says.

It requires a strong community. “We need more people to have different angles,” Derek says. Different takes on art and what it can be. “Kasi if kami lang, if it’s just us, it’s just one angle, I don’t think that’s viable to everyone kung ito lang ang meron.”

When we meet again on Zoom, Derek is back in La Union with Emerging Islands, to catch the end of surf season and to continue the community work he started this time last year.

“I met women in the market here, and they were selling fermented fruit vinegar and sila lang ang mayroong ganun,” Derek says. “So I interviewed them, bought all their vinegar, and invited them to a dinner using those vinegar. We talked about how they were made, tapos saan nila kinukuha, which was amazing. These fruits were just in their backyards, just wild.”

The encounter became the inspiration for his latest collaborative, multi-site project with UK-based curator and artist Ligaya Salazar and the British Council called “Wild Patch,” where they explore the symbolism of these wild and “undesirable” weeds and the parallels found in queer and diasporic communities.

Derek often takes a few months in a year to rest and research. It’s a period where he can incubate new ideas till they can find form and a home later on. His work for “A warm colored liquid” was inspired by his residency at the Jesuit-run Manila Observatory. His four-piece diorama for MCAD’s exhibit called “Adaptation: A Reconnected Earth”—a show aimed at fostering awareness and care of our planet’s ecological crisis— was a follow-up to Derek’s work with World Weather Network.

In particular, his nearly 27-ft tall paper mache sculpture called “Unearthing of a funny weather” was the result of two years of research into the effects of the global climate crisis in the Philippines. The sculpture is a replica of the controversial Australia-owned Didipio Mine in Nueva Vizcaya, one of the largest operating mines in the Philippines.

Derek tries to communicate the urgency of the situation through the work’s size. “[I wanted to expose] the scale of extraction that is happening in the Philippines,” says Derek. The work also traces the relationship of our experience of the climate crisis to colonialism. “I found out that most mining companies in the Philippines are either US, China, Canada, or Australia-owned. So most of the extraction actually goes out of the Philippines… Sobrang passive niya, which is actually so much worse, na parang hindi natin nakikita. There’s no war, there’s no tension.”

“I uncovered all that doing the climate research, which I did for almost two years with MCAD Manila Observatory. After that, I got so depressed, because I knew so much, and thought we’re fucked,” Derek says with a somber laugh.

“I asked myself, what am I going to do about this, with all this information? Maybe just keep on doing art. Try to extract all those ideas into whatever form it can be.”

“What attracts you to these kinds of topics?” I ask.

“I think I care too much about things, [that’s] the simple answer to it. The things that I do, and the works that I try to pursue… I feel like there’s a need for it. I’m not trying to solve [problems] really, but trying to articulate what’s happening today, I want to contribute to it. I feel like I can contribute to it.”

“I met women in the market here, and they were selling fermented fruit vinegar and sila lang ang mayroong ganun,” Derek says. “So I interviewed them, bought all their vinegar, and invited them to a dinner using those vinegar. We talked about how they were made, tapos saan nila kinukuha, which was amazing. These fruits were just in their backyards, just wild.”

The encounter became the inspiration for his latest collaborative, multi-site project with UK-based curator and artist Ligaya Salazar and the British Council called “Wild Patch,” where they explore the symbolism of these wild and “undesirable” weeds and the parallels found in queer and diasporic communities.

Derek often takes a few months in a year to rest and research. It’s a period where he can incubate new ideas till they can find form and a home later on. His work for “A warm colored liquid” was inspired by his residency at the Jesuit-run Manila Observatory. His four-piece diorama for MCAD’s exhibit called “Adaptation: A Reconnected Earth”—a show aimed at fostering awareness and care of our planet’s ecological crisis— was a follow-up to Derek’s work with World Weather Network.

In particular, his nearly 27-ft tall paper mache sculpture called “Unearthing of a funny weather” was the result of two years of research into the effects of the global climate crisis in the Philippines. The sculpture is a replica of the controversial Australia-owned Didipio Mine in Nueva Vizcaya, one of the largest operating mines in the Philippines.

Derek tries to communicate the urgency of the situation through the work’s size. “[I wanted to expose] the scale of extraction that is happening in the Philippines,” says Derek. The work also traces the relationship of our experience of the climate crisis to colonialism. “I found out that most mining companies in the Philippines are either US, China, Canada, or Australia-owned. So most of the extraction actually goes out of the Philippines… Sobrang passive niya, which is actually so much worse, na parang hindi natin nakikita. There’s no war, there’s no tension.”

“I uncovered all that doing the climate research, which I did for almost two years with MCAD Manila Observatory. After that, I got so depressed, because I knew so much, and thought we’re fucked,” Derek says with a somber laugh.

“I asked myself, what am I going to do about this, with all this information? Maybe just keep on doing art. Try to extract all those ideas into whatever form it can be.”

“What attracts you to these kinds of topics?” I ask.

“I think I care too much about things, [that’s] the simple answer to it. The things that I do, and the works that I try to pursue… I feel like there’s a need for it. I’m not trying to solve [problems] really, but trying to articulate what’s happening today, I want to contribute to it. I feel like I can contribute to it.”

Kaput’s “Corpcore” last January 2024. Photo by Gab Villareal.

Derek’s favorite parties have always been raves.

“It’s very special to me,” he begins. “[The rave] is a place where I can be most myself. I don’t know. I kind of feel it’s the most I can be myself without any inhibitions or whatever.”

The rave is a place to get inspired. To meet people from different walks of life united by the love of the rave. “You see a microcosm of society in one room,” he tells me. It’s techno hell. A love utopia. Whatever you want it to be, Derek says. “The rave really gave me that space to be free from all the expectations of what an artist can be, should be.”

But the rave was also an inspiration for Derek’s other ventures. “I like working with other people. Even when I’m researching, it still involves other people. I like bringing people together.” Derek says. “I guess it’s like the impulse of organizing a party.”

And this is Derek’s approach for his more ambitious works. He works closely with friends and collaborators who are all from different disciplines to create art in ways unexpected. “The works that are more complex are actually more collaborative. That’s also where scale comes from,” Derek says.

“Tropical Climate Forensics” required Derek to work closely with 3D artists, sound designers, and video game developers to realize. His work at MCAD and Art Fair Philippines was done with a family of paper mache artisans from Paete, as well as research from RENDER, an experimental climate change mitigation platform.

But while the rave influenced Derek’s approach to art, it took some time before he integrated actual raves into his art practice. This is what Derek attempted when he started Kaput Systems Inc. in 2022, an art and rave collective. When the UP Vargas Museum hosted a Kaput night called Vargas After-Hours in 2023, Derek saw it as validation.

“After I was able to do it in UP Vargas Museum I said sige, I'm going to put [the raves] in my CV,” Derek says with a laugh. “It kind of validated that [the rave] was actually part of my practice. People ask me ano ginagawa ko and I say I can do everything. Is it bad?”

Kaput co-founder and film producer Jan Pineda has been collaborating with Derek since 2019.

“I produced an event for then Globe Studios called .giff festival of new cinema. Derek was the curator for the audio-visual performances and the video art sections.” Jan writes over email.

“I feel like Kaput is an extension of this collaboration because it brings together different art forms into an experience.”

Each Kaput Night is different. Vargas After-Hours featured talks with the museum’s curator, followed by back-to-back sets by James Clar and Manila Animal (Kiko Escora), Badkiss (Christina Bartges), and Kevin Shaw. There have been installations and video works by Micaela Benedicto, Jao San Pedro, and Derek himself. The 5th edition of Kaput was in January 2024. The night was called “Corpcore,” a collaboration with Vancouver-based rave collective Normie Corp, with special ticket prices featuring titles like “Businesswoman Special” and “Late Inflation.”

When Derek talks about raves, there’s a physical aspect to it. How one can be pushed to their limits at a rave, but you can come out a different person. Much like life. Or a 10-day hike at Annapurna.

“Sometimes, [the rave can be] a harsh environment and it feels okay. You can also learn what life is about. For most of us, it’s like therapy in a way. You can also see it like meditation also, a way to get out of your body. I think it’s needed, so you don’t stay in one lane, one way of thinking.”

“It’s very special to me,” he begins. “[The rave] is a place where I can be most myself. I don’t know. I kind of feel it’s the most I can be myself without any inhibitions or whatever.”

The rave is a place to get inspired. To meet people from different walks of life united by the love of the rave. “You see a microcosm of society in one room,” he tells me. It’s techno hell. A love utopia. Whatever you want it to be, Derek says. “The rave really gave me that space to be free from all the expectations of what an artist can be, should be.”

But the rave was also an inspiration for Derek’s other ventures. “I like working with other people. Even when I’m researching, it still involves other people. I like bringing people together.” Derek says. “I guess it’s like the impulse of organizing a party.”

And this is Derek’s approach for his more ambitious works. He works closely with friends and collaborators who are all from different disciplines to create art in ways unexpected. “The works that are more complex are actually more collaborative. That’s also where scale comes from,” Derek says.

“Tropical Climate Forensics” required Derek to work closely with 3D artists, sound designers, and video game developers to realize. His work at MCAD and Art Fair Philippines was done with a family of paper mache artisans from Paete, as well as research from RENDER, an experimental climate change mitigation platform.

But while the rave influenced Derek’s approach to art, it took some time before he integrated actual raves into his art practice. This is what Derek attempted when he started Kaput Systems Inc. in 2022, an art and rave collective. When the UP Vargas Museum hosted a Kaput night called Vargas After-Hours in 2023, Derek saw it as validation.

“After I was able to do it in UP Vargas Museum I said sige, I'm going to put [the raves] in my CV,” Derek says with a laugh. “It kind of validated that [the rave] was actually part of my practice. People ask me ano ginagawa ko and I say I can do everything. Is it bad?”

Kaput co-founder and film producer Jan Pineda has been collaborating with Derek since 2019.

“I produced an event for then Globe Studios called .giff festival of new cinema. Derek was the curator for the audio-visual performances and the video art sections.” Jan writes over email.

“I feel like Kaput is an extension of this collaboration because it brings together different art forms into an experience.”

Each Kaput Night is different. Vargas After-Hours featured talks with the museum’s curator, followed by back-to-back sets by James Clar and Manila Animal (Kiko Escora), Badkiss (Christina Bartges), and Kevin Shaw. There have been installations and video works by Micaela Benedicto, Jao San Pedro, and Derek himself. The 5th edition of Kaput was in January 2024. The night was called “Corpcore,” a collaboration with Vancouver-based rave collective Normie Corp, with special ticket prices featuring titles like “Businesswoman Special” and “Late Inflation.”

When Derek talks about raves, there’s a physical aspect to it. How one can be pushed to their limits at a rave, but you can come out a different person. Much like life. Or a 10-day hike at Annapurna.

“Sometimes, [the rave can be] a harsh environment and it feels okay. You can also learn what life is about. For most of us, it’s like therapy in a way. You can also see it like meditation also, a way to get out of your body. I think it’s needed, so you don’t stay in one lane, one way of thinking.”

Derek’s film called “Living in a time without time,” which is part of a larger show called “winter high through the veins in search of hot weather” at Edoweird, opens with artist Mano Gonzales in bed in a dark room. Through the blanket, we see Mano’s phone light up, rousing him from his sleep. After a few minutes of watching Mano scroll through his phone, we’re taken through mesmerizing scenes. Lights change as do his outfits. The sound picks up, and we witness Mano doing push-ups and sprinting, then dancing feverishly to an endless techno beat. It’s a film with no script or lines. Only choreography, lights, and fashion—a rave.

It ends where it begins. Mano slowly slinks back to his bed in reverse. He tucks himself into bed and the room goes dark. The film loops and Mano’s phone lights up once more, and the day begins anew.

But the film is just one component of the show. To the left are four backlit panels, in what seems to be the same recycled abaca pulp that Derek used for “a warm colored liquid.” To the north of the room are Mano’s drawings on steel and paper. To the left is a terminal that runs the show’s credits, which include choreographer Shayna Laine Cua, sound designer Mario Consunji, and fashion by TOQA, all of whom are Derek’s friends.

It ends where it begins. Mano slowly slinks back to his bed in reverse. He tucks himself into bed and the room goes dark. The film loops and Mano’s phone lights up once more, and the day begins anew.

But the film is just one component of the show. To the left are four backlit panels, in what seems to be the same recycled abaca pulp that Derek used for “a warm colored liquid.” To the north of the room are Mano’s drawings on steel and paper. To the left is a terminal that runs the show’s credits, which include choreographer Shayna Laine Cua, sound designer Mario Consunji, and fashion by TOQA, all of whom are Derek’s friends.

“Living in a time without time“

“Living in a time without time“

The terminal also runs a poem that appears line by line. A few lines read: “there will be storms, the violence will unravel / but love, there is so much more than madness / the pleasures are waiting for you. / see them, be them. / the systems write itself, to be one with you.”

Sitting in the center of the room, one sees the universe that Derek has constructed since he began his art practice in earnest. The raves, the work in climate and the environment, the crossing of disciplines, and the transformational experiences that result from their collaboration.

This work feels very personal. A full-circle moment of a decade-old realization from walking through ice and stone in the moonlight for 10 days. But inherent in it is Derek’s invitation to his viewers. Armed with the knowledge that everything is connected, how do we move forward in a world that has taught us to think only of ourselves? How can we strengthen these connections? How can we be more ecological?

“The show at Edoweird is really trying to encapsulate my practice now,” Derek says. “I’m at a place where I can identify what my practice is without actually eliminating what I was experiencing back then. Who I was. What I was.”︎

![]()

Sitting in the center of the room, one sees the universe that Derek has constructed since he began his art practice in earnest. The raves, the work in climate and the environment, the crossing of disciplines, and the transformational experiences that result from their collaboration.

This work feels very personal. A full-circle moment of a decade-old realization from walking through ice and stone in the moonlight for 10 days. But inherent in it is Derek’s invitation to his viewers. Armed with the knowledge that everything is connected, how do we move forward in a world that has taught us to think only of ourselves? How can we strengthen these connections? How can we be more ecological?

“The show at Edoweird is really trying to encapsulate my practice now,” Derek says. “I’m at a place where I can identify what my practice is without actually eliminating what I was experiencing back then. Who I was. What I was.”︎

Toni Potenciano is a writer and strategist for And a Half.