Out of Print

This Time It’s Personal

by Sam Potenciano

Photos courtesy of Geloy Concepcion.

Photographer Geloy Concepcion on his career, leaving for the States, and how his latest project connected to so many all over the world.

In the first photo of the album, a woman and her son recline casually atop a concrete tomb, the shadows from which stretch out in the harsh midday sun. In another, a man backflips into grainy black and white waves next to a seaside shanty on stilts. Yet another: department store ladies working in tandem to disassemble a mannequin, bisecting it in order to stuff its limbs into a pair of skinny jeans. When the crude flash of the film camera goes off, one of them casts a questioning side-eye at the lens.

“Is it for us? Is it like a game about looking for the right composition or the perfect light? Is it about meeting people? Hearing stories? Telling stories? Or is it just about being alone? I don’t know. Why do you do it?”

︎

Three years ago, Geloy Concepcion made the difficult decision to step away from his career as a budding photographer in Manila to join his wife, Bea, in California, where she and her family had been living for over 10 years.

“Sobrang malaking desisyon ‘yan,” he shares. “Nagpakasal kami, nagka-baby kami, tapos parehas kaming nagdesisyon. ‘Yung naisip ko noon, ‘yung photography naman, kasama mo kahit saan. ‘Yun lang, kailangan mong iwan ‘yung career mo. Start from zero ka na naman.”

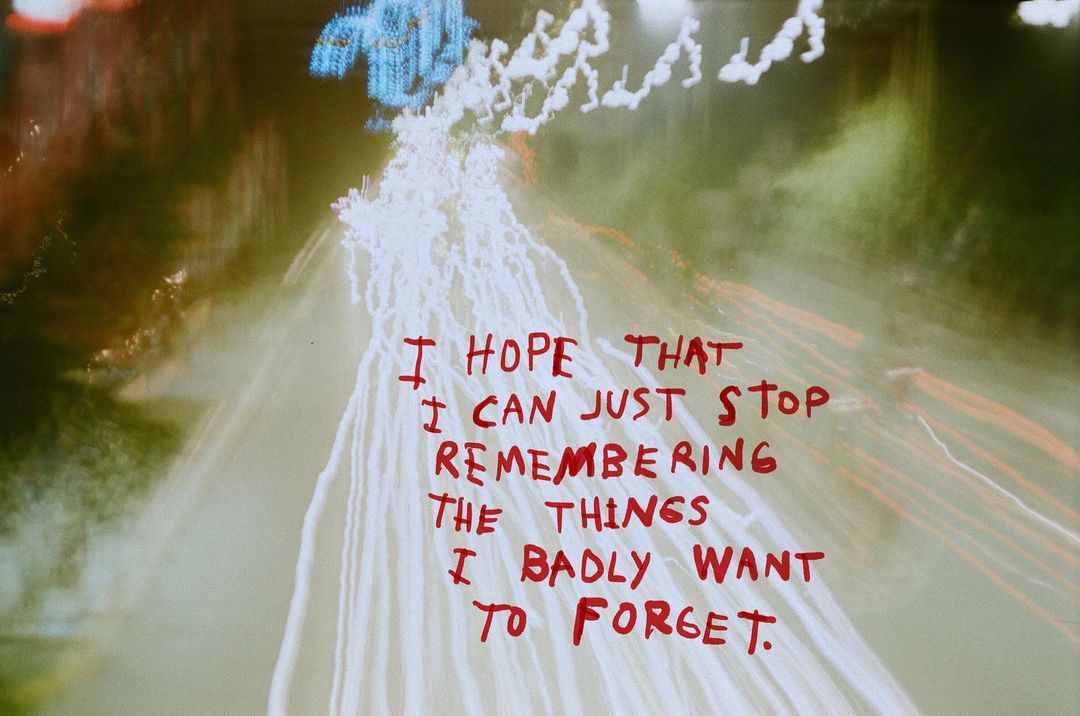

From Geloy’s ongoing project #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid

From Geloy’s ongoing project #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid

In the very beginning, starting from zero looked like this: an art student discovering photography apprehensively. “Noon, ‘yun talaga ‘yung akala kong magiging trabaho ko: pintor o illustrator o tattoo artist. Basta lahat tungkol sa drawing. Wala talaga akong kahit anong feeling kapag nakakakita ako ng camera,” Geloy shares.

Apart from borrowing a friend’s camera to complete a mandatory photography class at UST, he says he never felt compelled to pursue it until he began searching for a medium that could fully capture the stories that he came across during his time as a street artist.

“Mahilig talaga ako makipagkwentuhan,” he says. “Noong lumalabas kami para mag-street art, ang dami kong nami-meet at ang daming kwento. Hangga’t hindi ako na-satisfy sa mural lang. Naghanap ako ng ibang medium na mas intimate ‘yung usapan. Gusto ko ‘yung tao-tao talaga. Kasi ‘yung street art, ‘pag nagpe-paint kami, marami kami, tropa-tropa. ‘Pag nagshoo-shoot ako, mag-isa talaga ako.”

He credits fellow photographer Geric Cruz with opening him up further to the possibilities of portraiture. “Naaalala ko noon, nung street photography pa ginagawa ko, parang nababaduyan ako sa portraits. Parang ‘Ano ‘yan? Ganyan lang ‘yan?’ Sobrang hindi ko siya iniisip na gawin,” he laughs. “Si Geric, ‘yung best friend ko, siya ‘yung mas nagpo-portrait noon. ‘Yung nakita ko sa kanya, mas specific or mas micro ‘yung kwento kapag portraits. Dalawa lang kayong nag-uusap. Parang sentimental siya na paglalakbay. Personal siya.”

Geloy’s distinctive style of portraiture (“Ang sinasabi ng iba, ‘raw.’”) recalls the work of Robert Frank, the midcentury documentary photographer whose in-the-moment, snapshot-style photographs flew against the meticulously composed aesthetic of his time. Like Frank, Geloy’s work favors the highly personal over the glamorous—something which he has learned to work to his advantage.

“Hindi kasi ako nag-iilaw eh—kaya konti din ‘yung mga editorial assignment ko noon. Kumbaga, ‘yung ibang editor lang din ‘yung nakakaintindi sa akin. ‘‘Yun yung trip niya, eh! Ayaw niyang mukhang artista ‘yung artista. Dapat mukha lang taga-diyan.’ Kunwari ‘pag may ka-shoot akong artista, tapos may na-feel na ako para sa kaniya, trabaho lang ako... Mas maganda ‘pag nag-uusap talaga kayo.”

Assignments for high-profile publications such as VICE, Esquire, Town & Country, and CNN Philippines slowly but surely began trickling in. “‘Yun na ‘yung ikinabubuhay ko. Five years na akong nagshoo-shoot ng portraits,” he says, almost in disbelief.

Apart from borrowing a friend’s camera to complete a mandatory photography class at UST, he says he never felt compelled to pursue it until he began searching for a medium that could fully capture the stories that he came across during his time as a street artist.

“Mahilig talaga ako makipagkwentuhan,” he says. “Noong lumalabas kami para mag-street art, ang dami kong nami-meet at ang daming kwento. Hangga’t hindi ako na-satisfy sa mural lang. Naghanap ako ng ibang medium na mas intimate ‘yung usapan. Gusto ko ‘yung tao-tao talaga. Kasi ‘yung street art, ‘pag nagpe-paint kami, marami kami, tropa-tropa. ‘Pag nagshoo-shoot ako, mag-isa talaga ako.”

He credits fellow photographer Geric Cruz with opening him up further to the possibilities of portraiture. “Naaalala ko noon, nung street photography pa ginagawa ko, parang nababaduyan ako sa portraits. Parang ‘Ano ‘yan? Ganyan lang ‘yan?’ Sobrang hindi ko siya iniisip na gawin,” he laughs. “Si Geric, ‘yung best friend ko, siya ‘yung mas nagpo-portrait noon. ‘Yung nakita ko sa kanya, mas specific or mas micro ‘yung kwento kapag portraits. Dalawa lang kayong nag-uusap. Parang sentimental siya na paglalakbay. Personal siya.”

Geloy’s distinctive style of portraiture (“Ang sinasabi ng iba, ‘raw.’”) recalls the work of Robert Frank, the midcentury documentary photographer whose in-the-moment, snapshot-style photographs flew against the meticulously composed aesthetic of his time. Like Frank, Geloy’s work favors the highly personal over the glamorous—something which he has learned to work to his advantage.

“Hindi kasi ako nag-iilaw eh—kaya konti din ‘yung mga editorial assignment ko noon. Kumbaga, ‘yung ibang editor lang din ‘yung nakakaintindi sa akin. ‘‘Yun yung trip niya, eh! Ayaw niyang mukhang artista ‘yung artista. Dapat mukha lang taga-diyan.’ Kunwari ‘pag may ka-shoot akong artista, tapos may na-feel na ako para sa kaniya, trabaho lang ako... Mas maganda ‘pag nag-uusap talaga kayo.”

Assignments for high-profile publications such as VICE, Esquire, Town & Country, and CNN Philippines slowly but surely began trickling in. “‘Yun na ‘yung ikinabubuhay ko. Five years na akong nagshoo-shoot ng portraits,” he says, almost in disbelief.

“Ano ba ‘yung ikukuwento ko? Ano ‘yung sasabihin ko? Saan galing ‘yung boses ko?”

This steady stream of professional success most memorably found him trading and capturing stories in the company of both his own personal heroes (he recounts shooting behind-the-scenes of a Lav Diaz film where John Lloyd Cruz invited him to get into a van next to Ely Buendia and Dong Abay) and foes (another assignment involved portraits of a politician whose family’s regime had victimized his own father-in-law). The totality of these experiences and the stories that they allowed him to tell, he expresses utmost appreciation for.

“Nag-enjoy talaga ako kasi ang dami kong na-meet. ‘Yun ‘yung pinakapaborito ko, ‘yung makilala ang mga tao,” he reminisces. “Maraming instances na hanggang ngayon, naiisip ko pa rin. ‘Ba’t ako nandyan? Anong ginagawa ko diyan?’ Biruin mo—paano kami magkakakilala ni Erwin Romulo ‘pag nandoon lang ako sa amin? Kung saan-saan ka talaga nadadala ng kamera... Sa tingin ko, kung wala akong kamera, nandoon pa rin ako sa amin.”

Which takes us back to his decision to risk it all by starting over in America. “Siyempre, nasa isip ko na pagdating ko, itutuloy ko lang ‘yung ginagawa ko. Magme-message ako sa mga editor, ‘tatrabaho kaagad ako,” he says. What ended up happening was far beyond what he could have anticipated. Due to delays in the immigration process, he wasn’t allowed to legally seek any form of work for two years.

But rather than be discouraged by this major setback, Geloy admits that this total pause in his career ended up being the silver lining that he needed to reconnect with himself as an artist.

“Doon ako bumalik sa photography na mas personal. Kumbaga hindi na siya para sa ibang tao,” he realizes. “Sa Pilipinas, naging complacent din ako na mayroon na akong mga shoot, so hindi na ako gumawa ng mga personal work. Dito, parang na-pull ako ulit pabalik. Naalala ko noong nag-uumpisa pa lang ako, kailangan kong mag-build ulit ng mga koneksyon. Maganda ‘yung break na ‘yan at mahirap. Pero mas gusto ko siya kaysa sa kung nagtrabaho ako kaagad.”

Free from the constraints of having clients to please, editors to answer to, and most of all, time away from his art, Geloy began turning inward rather than out to rediscover his own voice. He explains that—while in the Philippines, he had the freedom to pick and choose from the many issues his work could speak for—in America, the story that he was most drawn to was his own.

“Ano ba ‘yung ikukuwento ko? Ano ‘yung sasabihin ko? Saan galing ‘yung boses ko?” he questioned. “Pagdating ko dito, mas malaki na ‘yung rine-represent ko. Tungkol sa immigrants na siya. Kaya ‘yun ‘yung unang ginawa ko. Tungkol sa bahay, sa pamilya ko, sa lahat ng nangyayari sa amin. ‘Yung natutunan ko, kuwento pa rin siya. At maraming tao na ganoon din ‘yung kuwento nila.”

The strange thing was that while the subject of his work (which he continued to share on social media) shifted increasingly towards the interior—the beautiful monotony of baptisms and showers, and naps on the couch with his wife and daughter—his following only continued to grow.

“Nag-enjoy talaga ako kasi ang dami kong na-meet. ‘Yun ‘yung pinakapaborito ko, ‘yung makilala ang mga tao,” he reminisces. “Maraming instances na hanggang ngayon, naiisip ko pa rin. ‘Ba’t ako nandyan? Anong ginagawa ko diyan?’ Biruin mo—paano kami magkakakilala ni Erwin Romulo ‘pag nandoon lang ako sa amin? Kung saan-saan ka talaga nadadala ng kamera... Sa tingin ko, kung wala akong kamera, nandoon pa rin ako sa amin.”

Which takes us back to his decision to risk it all by starting over in America. “Siyempre, nasa isip ko na pagdating ko, itutuloy ko lang ‘yung ginagawa ko. Magme-message ako sa mga editor, ‘tatrabaho kaagad ako,” he says. What ended up happening was far beyond what he could have anticipated. Due to delays in the immigration process, he wasn’t allowed to legally seek any form of work for two years.

But rather than be discouraged by this major setback, Geloy admits that this total pause in his career ended up being the silver lining that he needed to reconnect with himself as an artist.

“Doon ako bumalik sa photography na mas personal. Kumbaga hindi na siya para sa ibang tao,” he realizes. “Sa Pilipinas, naging complacent din ako na mayroon na akong mga shoot, so hindi na ako gumawa ng mga personal work. Dito, parang na-pull ako ulit pabalik. Naalala ko noong nag-uumpisa pa lang ako, kailangan kong mag-build ulit ng mga koneksyon. Maganda ‘yung break na ‘yan at mahirap. Pero mas gusto ko siya kaysa sa kung nagtrabaho ako kaagad.”

Free from the constraints of having clients to please, editors to answer to, and most of all, time away from his art, Geloy began turning inward rather than out to rediscover his own voice. He explains that—while in the Philippines, he had the freedom to pick and choose from the many issues his work could speak for—in America, the story that he was most drawn to was his own.

“Ano ba ‘yung ikukuwento ko? Ano ‘yung sasabihin ko? Saan galing ‘yung boses ko?” he questioned. “Pagdating ko dito, mas malaki na ‘yung rine-represent ko. Tungkol sa immigrants na siya. Kaya ‘yun ‘yung unang ginawa ko. Tungkol sa bahay, sa pamilya ko, sa lahat ng nangyayari sa amin. ‘Yung natutunan ko, kuwento pa rin siya. At maraming tao na ganoon din ‘yung kuwento nila.”

The strange thing was that while the subject of his work (which he continued to share on social media) shifted increasingly towards the interior—the beautiful monotony of baptisms and showers, and naps on the couch with his wife and daughter—his following only continued to grow.

Early on, Geloy admits a sense of surrealness or even a bit of discomfort when he started getting more high-profile projects in Manila. “Maraming instances na hanggang ngayon, naiisip ko pa rin. ‘Ba’t ako nandyan? Anong ginagawa ko diyan?’” he says.

“Nagulat ako na sumabog talaga ‘yan. Hindi ko inaasahan,” says Geloy of the success of #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid. It was a personl project that has transformed into something that’s more inclusive. “Nung tumagal, naisip ko, hindi na ‘to sa akin. Sa totoo lang, hindi ko siya inaangkin. Para na siyang community.”

I ask whether he was surprised that something so personal could still resonate with an audience from around the world—let alone one that had never even met him nor his family. “Alam mo sobrang weird talaga. Gulat ako na kahit personal lang siya sa akin, kagaya ng picture ng asawa o anak ko, okay lang. Ganoon pa rin ba ‘yung pakiramdam ng mga tao sa mga ibang picture ko? Sabi ng nanay ko sa akin, ‘Honest ka siguro, kaya pinagkakatiwalaan ka ng mga tao.’”

Despite this, towards the tail end of this two-year hiatus, he says he finally reached a breaking point. “Wala pa rin ‘yung work permit ko. Medyo nasa brink na ako. Naisip ko na ayoko na mag-photography. Pahinga muna ako. Napunta ako sa stage na ‘yan nung January,” he says. “Tapos biglang naalala ko na may ginawa akong poll sa Instagram nung November. Nagtanong ako: ‘Ano ‘yung gusto mong sabihin na hindi mo masabi?’”

Having filed away the many responses to that poll, it dawned on him that this could be the basis for a project that served a dual purpose. First as a platform for people to voice their confessions anonymously, and second as a way to make use of his old photos that he had deemed unusable. By vandalizing his own images with the handwritten words of others, the collaborative #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid was born.

The unexpected timing of which also happened to propel it to instant online renown. “Nagulat ako na sumabog talaga ‘yan. Hindi ko inaasahan. Tapos sumakto siya sa pandemic... Dahil nasa bahay lang ‘yung mga tao at panay isip lang sila... Siguradong nagkaroon ng epekto iyan,” he reflects.

“Noong una, project ko pa siya. Sa end ko, gusto ko rin magpakita ng iba kong litrato, bukod sa mag-provide ng safe space. Pero nung tumagal, naisip ko, hindi na ‘to sa akin. Sa totoo lang, hindi ko siya inaangkin. Para na siyang community.”

Despite this, towards the tail end of this two-year hiatus, he says he finally reached a breaking point. “Wala pa rin ‘yung work permit ko. Medyo nasa brink na ako. Naisip ko na ayoko na mag-photography. Pahinga muna ako. Napunta ako sa stage na ‘yan nung January,” he says. “Tapos biglang naalala ko na may ginawa akong poll sa Instagram nung November. Nagtanong ako: ‘Ano ‘yung gusto mong sabihin na hindi mo masabi?’”

Having filed away the many responses to that poll, it dawned on him that this could be the basis for a project that served a dual purpose. First as a platform for people to voice their confessions anonymously, and second as a way to make use of his old photos that he had deemed unusable. By vandalizing his own images with the handwritten words of others, the collaborative #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid was born.

The unexpected timing of which also happened to propel it to instant online renown. “Nagulat ako na sumabog talaga ‘yan. Hindi ko inaasahan. Tapos sumakto siya sa pandemic... Dahil nasa bahay lang ‘yung mga tao at panay isip lang sila... Siguradong nagkaroon ng epekto iyan,” he reflects.

“Noong una, project ko pa siya. Sa end ko, gusto ko rin magpakita ng iba kong litrato, bukod sa mag-provide ng safe space. Pero nung tumagal, naisip ko, hindi na ‘to sa akin. Sa totoo lang, hindi ko siya inaangkin. Para na siyang community.”

The striking visual effect of #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid is at once unflinching and emotionally raw, yet still comforting and strangely familiar. “Dahil anonymous siya, ‘pag nabasa mo, walang mukha. Pwedeng inimbento ko lang siya, or [nanggagaling ito sa] lahat ng tao. Pwede siyang lahat tayo or wala sa atin,” Geloy says. “Sa tingin ko ‘yan ‘yung kagandahan ng anonymity. Hindi mo nabo-box sa isang mukha. Mas fluid siya. Pwedeng ikaw siya, pwedeng ako, pwedeng nanay mo. Hindi mo kilala ang nagsulat.”

This fluidity extends to the overall form of the project itself. Having begun partly as a medium for his unseen work, it has since evolved to include images submitted by strangers, to possibly, in the future, forgotten photos found at thrift stores. The open-ended nature of this work-in-progress is something that speaks to Geloy on a personal level.

“Maraming nagme-message sa akin na nakakatulong at liberating siya. Pero para sa akin, liberating din siya para sa proseso ko—na pwede pala akong mag-produce ng work na wala akong material. Hindi lang ako na-box sa pagiging photographer. Natutunan ko na mas kailangan kong isipin ‘yung dahilan o purpose kaysa sa idea ng photography.”

![]()

At the end of our Zoom call (mid-day in Manila, close to bedtime in California), Geloy apologizes again for not getting back to me sooner. His schedule is understandably hectic. At his day job as a dishwasher at the cafe his wife’s family owns, he’s on his feet for eight hours, lifting his weight in tableware and running his fingers to the bone over a hot sink. He says he enjoys the newfound physical discipline that this job has given him. “Ang problema lang, meron akong scoliosis. So minsan pagod na ako, gusto ko na umupo—pero baka ma-fire ako, eh!” he laughs.

The few after-hours he has are spent working through the many submissions for #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid, finding ways to incorporate them into photographs, answering questions for the occasional journalist, and having dinner with his wife and daughter.

Narra, a constant fixture in his work since the day she was born, just recently turned three. “Noong unang dumating ako dito, birthday ng anak ko,” he reflects. “Parang kaming magkasing edad dito sa States. Parang sabay kami pinanganak.” ︎

This fluidity extends to the overall form of the project itself. Having begun partly as a medium for his unseen work, it has since evolved to include images submitted by strangers, to possibly, in the future, forgotten photos found at thrift stores. The open-ended nature of this work-in-progress is something that speaks to Geloy on a personal level.

“Maraming nagme-message sa akin na nakakatulong at liberating siya. Pero para sa akin, liberating din siya para sa proseso ko—na pwede pala akong mag-produce ng work na wala akong material. Hindi lang ako na-box sa pagiging photographer. Natutunan ko na mas kailangan kong isipin ‘yung dahilan o purpose kaysa sa idea ng photography.”

“Dito, parang na-pull ako ulit pabalik,” says Geloy. “Naalala ko na noong nag-uumpisa palang ako, kailangan ko mag-build ulit ng mga koneksyon.”

At the end of our Zoom call (mid-day in Manila, close to bedtime in California), Geloy apologizes again for not getting back to me sooner. His schedule is understandably hectic. At his day job as a dishwasher at the cafe his wife’s family owns, he’s on his feet for eight hours, lifting his weight in tableware and running his fingers to the bone over a hot sink. He says he enjoys the newfound physical discipline that this job has given him. “Ang problema lang, meron akong scoliosis. So minsan pagod na ako, gusto ko na umupo—pero baka ma-fire ako, eh!” he laughs.

The few after-hours he has are spent working through the many submissions for #ThingsYouWantedToSayButNeverDid, finding ways to incorporate them into photographs, answering questions for the occasional journalist, and having dinner with his wife and daughter.

Narra, a constant fixture in his work since the day she was born, just recently turned three. “Noong unang dumating ako dito, birthday ng anak ko,” he reflects. “Parang kaming magkasing edad dito sa States. Parang sabay kami pinanganak.” ︎

Sam Potenciano is a former magazine editor and stylist currently doing creative odd jobs in Manila.