Out

of Print

Isha Naguiat Can Never Leave Home

by Jonty Cruz

Photos courtesy of Isha Naguiat.

Through her art, Isha Naguiat ties her most precious memories to the realities of today.

Isha Naguiat is an artist whose work has been shown in some of the country's best galleries, from Blanc to West to Finale Art File just to name a few. She graduated cum laude from the University of the Philippines’ College of Fine Arts in 2015, and in 2017 was an artist-in-residence at Takt Artist Residency in Berlin, Germany. But for all her outward accomplishments, it is home where most of her art returns to. Not of home as brick and mortar, but of its memory and how we question it.

When I ask Isha of her earliest memories, she’s quick to point out that she’s not at all certain if it was something that really happened. She wonders if it was all just a product of her vivid imagination disguising itself as an innocent memory. Nevertheless, in her mind’s eye, she sees herself as a child dancing on top of the kitchen counter in her first home. Her childhood, she says, was spent dancing to Britney Spears, fighting with her four brothers for control of the TV remote—she’s the middle child of five as well as the only girl—and riding her bicycle around the village. It sounds like a typical childhood, but she says there was a certain emphasis placed on her of how she and her siblings were “different.” She says she was “painfully shy” and wanted nothing more than just to be at home all time. “I loved being at home so much that sometimes I would get a fleeting feeling of homesickness when I would be out, even just for a few hours,” she says, “like being tethered to the house and someone is tugging at the string. I still feel that sometimes.”

That feeling of being tethered is evident in most of Isha’s work. As an artist, she employs different mediums and ties them together to articulate a multitude of her feelings of home and memory. Old family portraits brought together through string and fabric. Childhood garments sewn with lines and passages embroidered by hand. Remnants of the past encased in silk houses. These artifacts serve as Isha’s validation and deconstruction of her memories, bringing them to the forefront in ways that both highlight and examine the past. “Memory is something that I like to talk about in my art, but I also recognize how much of memory is idealized. I found that a criticism of nostalgia is its idealizations,” she says. “Memory is malleable and every time we access those memories, sometimes, we can’t help but color them in pink as we grow older.”

Perhaps memory and the idea of home are just one and the same. What could be more nostalgic than the memory of a warm and loving home? What is home but the space where our most treasured memories nest? In a way, her art serves as tiny monuments to her memories. As JC Rosette writes for Isha’s show at Finale Art File back in 2019, “This Used to be a House”: “Naguiat juxtaposes past and present, rendering the house’s structure in flux and recalling gaps in time that led to its transfiguration,” and later goes on to say that the idea of a past home, “even in ruins, can summon the perpetual sunshine of carefree days, the insouciant crash of waves.”

For as much as Isha brings her memories and ideas of home out for the world to see, the more it ties tighter and tighter to her. If it is true that we can never really leave home, then Isha’s work is proof of what Maya Angelou believed that one will always carry “the shadows, the fears, and the dragons of home under one's skin…”

The following was conducted over email and has been edited for publication.

“I felt some pressure to turn my art degree into a ‘real job,’” says Isha when she worked at an art gallery after college. While it did give her some stability, the call to create for herself never left. “All I could think about was how much I wanted to create the works being hung in the gallery, not just hanging them.”

Out of Print: Hi Isha! When did art first come into your life?

Isha Naguiat: I was enrolled in a preschool that emphasized learning based on the multiple intelligence theory. The multiple intelligence theory categorizes nine different ways a child can learn and acquire information. Quickly, I learned that I was “art smart,” and ever since, I just leaned on to that label. I took a lot of art classes after discovering that “smart,” and it was my art teacher in grade school who inspired me to go to UP Fine Arts.

So would it be fair to say you always felt you were meant to be an artist?

I only remember saying I wanted to be an artist growing up. There were times when I considered some other career in high school, but it always came down to a career with art. However, I feel like I was sort of in denial about it for a time, too—I didn’t really fully realize that this is really the path I would be taking till a few years after college. After college, I just wanted to work in a gallery. I felt some pressure to turn my art degree into a “real job,” and when I did, all I could think about was how much I wanted to create the works being hung in the gallery, not just hanging them. It took some soul searching for me to finally realize that being an artist is a path that I’ve long since chosen.

What did you learn about the art world/community from working in a gallery?

I learned about the realities of the art world. My parents are business people so growing up, they instilled in me an entrepreneurial mindset. I had to stay away from that mindset in Fine Arts in order to focus on art that has substance. I remember professors saying that “sellability” should be the last thing on your mind when creating. Entering the art world as a gallery assistant made me realize it’s a balance. Some artists are lucky to have gallerists that back them so that they can concentrate on art making, but as an independent artist I had to learn how to do the business side of being an artist as well.

You majored in painting in U.P. May I ask what made you love painting and when/why did you transition into other mediums?

What made me love painting was the process. I loved getting lost in the zone and just spending hours with a paintbrush in hand. But I also loved stepping back and problem-solving: seeing what’s lacking and figuring out how to say what I want to say in the image.

Before entering U.P., my small high school awarded me the “Spatial Intelligence Award” during graduation. It felt good to be recognized, but once I got to Fine Arts, it was really hard. Everyone was so advanced, and I felt so dumb and out of place. During my first year, I considered transferring out of U.P. But I toughed it out, and in Junior year, we were freer to explore different mediums. In a class with Sir Jonathan Olazo, he gave us an assignment to create works for three different fictitious artists. We had to make up three artists and make up background info about them and make artworks that these “artists” would make in different styles. For one artist, I made a portrait and embroidered it on the canvas with yarn. Something clicked and I just started to use fiber more in my art works. I haven’t painted in years, and honestly, I think I lost the joy in painting, but maybe someday I can start again, even just for myself.

Would you mind sharing that experience of losing the joy in painting? And perhaps how you think you can get it back?

It’s tough because once you don’t practice a skill, you lose it. When I try to paint after not painting for a long time, it doesn’t turn out the way I want it to and so I avoid painting. It’s an endless cycle. My mind always thinks about what my peers or professors would say if I showed a certain painting or work during a critique. Sometimes I need to remind myself that I’m not in Fine Arts anymore. I don’t have to defend my work like I used to. I think I just need to get over that hump of caring what people will think and just paint for myself.

Isha Naguiat: I was enrolled in a preschool that emphasized learning based on the multiple intelligence theory. The multiple intelligence theory categorizes nine different ways a child can learn and acquire information. Quickly, I learned that I was “art smart,” and ever since, I just leaned on to that label. I took a lot of art classes after discovering that “smart,” and it was my art teacher in grade school who inspired me to go to UP Fine Arts.

So would it be fair to say you always felt you were meant to be an artist?

I only remember saying I wanted to be an artist growing up. There were times when I considered some other career in high school, but it always came down to a career with art. However, I feel like I was sort of in denial about it for a time, too—I didn’t really fully realize that this is really the path I would be taking till a few years after college. After college, I just wanted to work in a gallery. I felt some pressure to turn my art degree into a “real job,” and when I did, all I could think about was how much I wanted to create the works being hung in the gallery, not just hanging them. It took some soul searching for me to finally realize that being an artist is a path that I’ve long since chosen.

What did you learn about the art world/community from working in a gallery?

I learned about the realities of the art world. My parents are business people so growing up, they instilled in me an entrepreneurial mindset. I had to stay away from that mindset in Fine Arts in order to focus on art that has substance. I remember professors saying that “sellability” should be the last thing on your mind when creating. Entering the art world as a gallery assistant made me realize it’s a balance. Some artists are lucky to have gallerists that back them so that they can concentrate on art making, but as an independent artist I had to learn how to do the business side of being an artist as well.

You majored in painting in U.P. May I ask what made you love painting and when/why did you transition into other mediums?

What made me love painting was the process. I loved getting lost in the zone and just spending hours with a paintbrush in hand. But I also loved stepping back and problem-solving: seeing what’s lacking and figuring out how to say what I want to say in the image.

Before entering U.P., my small high school awarded me the “Spatial Intelligence Award” during graduation. It felt good to be recognized, but once I got to Fine Arts, it was really hard. Everyone was so advanced, and I felt so dumb and out of place. During my first year, I considered transferring out of U.P. But I toughed it out, and in Junior year, we were freer to explore different mediums. In a class with Sir Jonathan Olazo, he gave us an assignment to create works for three different fictitious artists. We had to make up three artists and make up background info about them and make artworks that these “artists” would make in different styles. For one artist, I made a portrait and embroidered it on the canvas with yarn. Something clicked and I just started to use fiber more in my art works. I haven’t painted in years, and honestly, I think I lost the joy in painting, but maybe someday I can start again, even just for myself.

Would you mind sharing that experience of losing the joy in painting? And perhaps how you think you can get it back?

It’s tough because once you don’t practice a skill, you lose it. When I try to paint after not painting for a long time, it doesn’t turn out the way I want it to and so I avoid painting. It’s an endless cycle. My mind always thinks about what my peers or professors would say if I showed a certain painting or work during a critique. Sometimes I need to remind myself that I’m not in Fine Arts anymore. I don’t have to defend my work like I used to. I think I just need to get over that hump of caring what people will think and just paint for myself.

As someone who works on the idea of home, what was living in Berlin like?

I loved living in Berlin. The residency was my first taste of independence and as much as I loved it, it was also really hard. I felt that string from home tugging in moments of silence. My anxiety manifested itself on my body, making my skin feel itchy. I would scratch my skin obsessively, leaving raised red marks. This continued weeks into my residency. On top of being in a new city, I was also dealing with imposter syndrome. I tend to overthink, and to calm myself down, I started to embroider a piece of fabric that was left behind by the previous occupant. This 60-inch piece of fabric became my meditation when I would get overwhelmed. I worked on the piece day by day as I adjusted to the new city little by little.

![]()

I really love how you employ embroidery in your art, could you share when your fascination with that started?

I considered a career in fashion at one point, so when it came to art making, I just automatically gravitated towards textiles. I started to take embroidery more seriously when I was doing my thesis. I used old barongs from my relatives to create fabric houses. I studied the embroideries on the barongs and figured I could probably do that. Spoiler: it’s not that easy but I began to make it my own.

Is there a particular fabric or method you’ve really gravitated towards in your art?

I’m drawn to sheer fabric, particularly piña, jusi, and organza. I used jusi a lot in my work ever since I discovered it during my thesis. I found that transferring images on to jusi was easy and its stiffness can also make it great for my fabric sculptures.

I loved living in Berlin. The residency was my first taste of independence and as much as I loved it, it was also really hard. I felt that string from home tugging in moments of silence. My anxiety manifested itself on my body, making my skin feel itchy. I would scratch my skin obsessively, leaving raised red marks. This continued weeks into my residency. On top of being in a new city, I was also dealing with imposter syndrome. I tend to overthink, and to calm myself down, I started to embroider a piece of fabric that was left behind by the previous occupant. This 60-inch piece of fabric became my meditation when I would get overwhelmed. I worked on the piece day by day as I adjusted to the new city little by little.

Hidden Uneasiness, Isha Naguiat, 2017, Thread and watercolor on canvas.

How did the idea of “the house” change or reveal itself to you during your time in Berlin?

Down the street where I lived was an Asian grocery. In moments of homesickness, I would drop 4 euros for a pack of pancit canton. (It hurts to think how much money I spent when I convert it into pesos haha). But I think during my time there, I realized that “home” may be a place, but it’s also the little things that truly make it what you miss.

Down the street where I lived was an Asian grocery. In moments of homesickness, I would drop 4 euros for a pack of pancit canton. (It hurts to think how much money I spent when I convert it into pesos haha). But I think during my time there, I realized that “home” may be a place, but it’s also the little things that truly make it what you miss.

I really love how you employ embroidery in your art, could you share when your fascination with that started?

I considered a career in fashion at one point, so when it came to art making, I just automatically gravitated towards textiles. I started to take embroidery more seriously when I was doing my thesis. I used old barongs from my relatives to create fabric houses. I studied the embroideries on the barongs and figured I could probably do that. Spoiler: it’s not that easy but I began to make it my own.

Is there a particular fabric or method you’ve really gravitated towards in your art?

I’m drawn to sheer fabric, particularly piña, jusi, and organza. I used jusi a lot in my work ever since I discovered it during my thesis. I found that transferring images on to jusi was easy and its stiffness can also make it great for my fabric sculptures.

Where were you last year during the pandemic and how did you cope being in

lockdown?

I was at home with my parents and my oldest brother during the first few weeks of lockdown. My two youngest brothers flew out to New Zealand for college a month before everything closed down, and my newlywed older brother was living with his wife in a condo. I was so used to having a full house all my life and then it was suddenly so quiet. A few weeks into lockdown, my brother and sister-in-law joined our bubble and then eventually my boyfriend moved in too. I felt some relief to have my loved ones close to me and to hear the noise of the house come alive again.

Like most people at the start of lockdown, I coped by baking and eating a lot of bread. I also tried to settle my anxiety by starting on new projects. Alongside embroidery, I took a chance and ventured on to a new medium: cyanotypes.

What was it like working on/with a new medium? What comforts or creative inspiration did it give you?

It was invigorating to be working with a new medium. I loved the experimentation you can do with cyanotypes. After working on fabrics and embroideries for a long time, working with a new medium felt like a much-needed jolt. I had zero experience with cyanotypes when I started so there was a lot of trial and error. But once I figured out what worked for me, the ideas just flowed and kept me busy. Being focused on this new medium kept me too occupied to be anxious during this time of uncertainty.

lockdown?

I was at home with my parents and my oldest brother during the first few weeks of lockdown. My two youngest brothers flew out to New Zealand for college a month before everything closed down, and my newlywed older brother was living with his wife in a condo. I was so used to having a full house all my life and then it was suddenly so quiet. A few weeks into lockdown, my brother and sister-in-law joined our bubble and then eventually my boyfriend moved in too. I felt some relief to have my loved ones close to me and to hear the noise of the house come alive again.

Like most people at the start of lockdown, I coped by baking and eating a lot of bread. I also tried to settle my anxiety by starting on new projects. Alongside embroidery, I took a chance and ventured on to a new medium: cyanotypes.

What was it like working on/with a new medium? What comforts or creative inspiration did it give you?

It was invigorating to be working with a new medium. I loved the experimentation you can do with cyanotypes. After working on fabrics and embroideries for a long time, working with a new medium felt like a much-needed jolt. I had zero experience with cyanotypes when I started so there was a lot of trial and error. But once I figured out what worked for me, the ideas just flowed and kept me busy. Being focused on this new medium kept me too occupied to be anxious during this time of uncertainty.

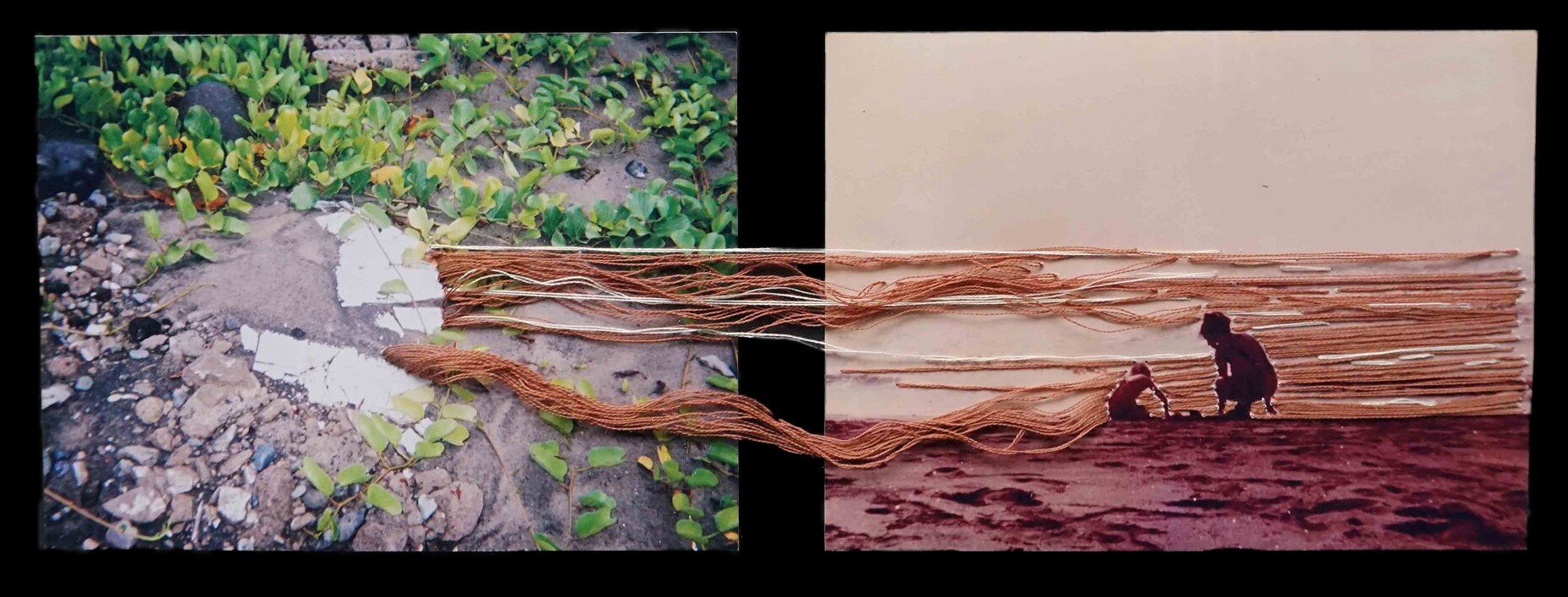

From “This Used to be a House”: Decades Apart 9, Isha Naguiat, 2019, Thread on photographs. Decades Apart I, Isha Naguiat, 2019, Thread on photographs.

From Isha Naguiat’s “In Flux” at Underground Gallery in Makati.

From Isha Naguiat’s “In Flux” at Underground Gallery in Makati.Which show that you’ve done or been a part of do you look back on or revisit the most?

I think about my last solo show, “In Flux” in Underground a lot. It opened one week before lockdown. I was really proud of how it turned out, but not a lot of people saw it in person.

Which show do you feel took the longest to put together?

My solo show, “This Used to be a House” in Finale took the longest to put together. A year before the show, I submitted a proposal inspired by a trip to the beach my family went to when I was a kid. The photos and videos I took of that beach showed remnants of a house that was slowly being reclaimed by the ocean. By the time I started working on the show, the images and videos I sent in for the proposal were 2 years old. I decided to travel back to La Union from Manila to get more material and when I arrived, there was nothing. I had to rethink everything. Eventually, I made three more trips to that beach and a lot of soul searching for me to finish the show.

I’ve always been so curious about the process of the show proposal. Could you share how that works and what do gallerists usually look for when it comes to a good proposal?

I was already part of several group shows before I started proposing for solo shows. Through those group shows, I was able to establish relationships with different galleries. I choose the galleries I think would show my kind of work and then I basically just email them my proposals and hope they take a chance on me. It’s always great to have a strong concept when proposing a show but galleries know that the concept can always evolve.

I think about my last solo show, “In Flux” in Underground a lot. It opened one week before lockdown. I was really proud of how it turned out, but not a lot of people saw it in person.

Which show do you feel took the longest to put together?

My solo show, “This Used to be a House” in Finale took the longest to put together. A year before the show, I submitted a proposal inspired by a trip to the beach my family went to when I was a kid. The photos and videos I took of that beach showed remnants of a house that was slowly being reclaimed by the ocean. By the time I started working on the show, the images and videos I sent in for the proposal were 2 years old. I decided to travel back to La Union from Manila to get more material and when I arrived, there was nothing. I had to rethink everything. Eventually, I made three more trips to that beach and a lot of soul searching for me to finish the show.

I’ve always been so curious about the process of the show proposal. Could you share how that works and what do gallerists usually look for when it comes to a good proposal?

I was already part of several group shows before I started proposing for solo shows. Through those group shows, I was able to establish relationships with different galleries. I choose the galleries I think would show my kind of work and then I basically just email them my proposals and hope they take a chance on me. It’s always great to have a strong concept when proposing a show but galleries know that the concept can always evolve.

From “Intersection/Likas” a two-man show by Isha Naguiat and Mila Bubliy. Photo by Vinly on Vinly and courtesy of Isha Naguiat.

Beyond the house, you’ve also expanded to working on the idea of place in at least two shows (Traces and Intersection/Likas), how do places work as another medium for you?

Places as a medium for me is sort of like stepping out of the house; it stops me from thinking so inwardly and start relating to my surroundings. With “Intersection/Likas” and “This Used to be a House,” I was able to touch on the climate crisis and the changing environments.

“Intersection/Likas” was a two-woman show with my collaborator, Mila Bubliy. Mila is from Germany and our collaborations are entirely done online and for this show we wanted to highlight the importance of place and its changing environments. Our projects together deal a lot about our different and shared experiences as people across the globe from each other.

What excites you most about art or being an artist in the coming months?

I think along with the dark days the pandemic has brought was a thirst for art. It excites me to see a renewed enthusiasm for supporting artists in the community. Being forced into lockdown has produced plenty of meaningful and contemplative works from artists. I’m excited to produce works for my upcoming solo show in Vinyl on Vinyl in March. The works I’m producing are a direct influence of the experimentation I did with cyanotypes and embroidery during quarantine.︎

Places as a medium for me is sort of like stepping out of the house; it stops me from thinking so inwardly and start relating to my surroundings. With “Intersection/Likas” and “This Used to be a House,” I was able to touch on the climate crisis and the changing environments.

“Intersection/Likas” was a two-woman show with my collaborator, Mila Bubliy. Mila is from Germany and our collaborations are entirely done online and for this show we wanted to highlight the importance of place and its changing environments. Our projects together deal a lot about our different and shared experiences as people across the globe from each other.

What excites you most about art or being an artist in the coming months?

I think along with the dark days the pandemic has brought was a thirst for art. It excites me to see a renewed enthusiasm for supporting artists in the community. Being forced into lockdown has produced plenty of meaningful and contemplative works from artists. I’m excited to produce works for my upcoming solo show in Vinyl on Vinyl in March. The works I’m producing are a direct influence of the experimentation I did with cyanotypes and embroidery during quarantine.︎

Jonty Cruz is a writer and creative consultant based in Manila.