Out of Print

The Tender Eye of JL Javier

by Toni Potenciano

Images courtesy of JL Javier.

Banner image by Reymart Cerin.

International Photography Award winner JL Javier talks about photojournalism, self-doubt, and finding meaning in the practice of photography.

I ask photographer JL Javier as we ended our final interview. It’s a cheat question, absurd to even ask — even borders on rude.

Here’s the deal with surviving the pandemic in Manila: You’re at least somewhat miserable. Maybe you were for some time now. Either you haven’t gone anywhere or seen anyone for a year and a half, or; you risk your life everyday by going out to work, exposed to all the dangers of this inhospitable city because you have no choice: Risk Covid-19 or die of hunger.

Is anybody truly happy these days? If imagining a future is impossible, then it makes sense why all of us hold on to the past a little more tenderly. We ration one happy memory and spread it out thinly — a balm to soothe and last us another month, week, a day.

JL pauses before he speaks. “Siguro ‘yung last is ‘yung [photo I took] sa Baseco Beach of these kids doing backflips out of nowhere.”

He tells me about the time he went out last March to cover the city under lockdown as staff photographer for CNN Philippines Life. That day, while in the general vicinity of the city of Manila, he took the opportunity to check out Baseco Beach in Tondo.

The coastal compound of Baseco is home to at least 59,000 informal settlers, making it one of the largest slums in Metro Manila. It used to be a dockyard for ships until 1964, when it was acquired by the Romualdez family – a direct kin of Imelda Marcos, wife of former president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos – and renamed to Bataan Shipping and Engineering Company or BASECO.

When the Marcoses fell from power, Baseco was sequestered by President Corazon Aquino, shortly after many urban poor communities resettled into the area.

It gained notoriety in the 2000s both here and abroad when residents made merchandise of their own kidneys just to get by.

The Health Department declared Baseco Beach’s waters “unsafe for swimming” due to the high levels of coliform, but residents still flocked by the thousands. “I cannot afford to bring my kids to expensive beach resorts so we decided to swim in Manila Bay. We brought food and drinks,” reads a quote from a March 2021 report by the Philippine Star.

The black and white photoset JL brought home from Baseco that day is entitled “Neverland.” The first photo features three boys. In the background, a boy with bleached hair is smiling; the second one is holding a plate — his mouth full of rice as he gazes up almost suspiciously at the third boy who is suspended in the air mid-backflip.

It’s a picture of pure joy, captured on camera by a tender and observant eye. This is the mark of JL’s photography: Deeply sensitive to the richness of humanity. His photos emanate care and respect for his subjects with an eye for intimate details.

The Health Department declared Baseco Beach’s waters “unsafe for swimming” due to the high levels of coliform, but residents still flocked by the thousands. “I cannot afford to bring my kids to expensive beach resorts so we decided to swim in Manila Bay. We brought food and drinks,” reads a quote from a March 2021 report by the Philippine Star.

The black and white photoset JL brought home from Baseco that day is entitled “Neverland.” The first photo features three boys. In the background, a boy with bleached hair is smiling; the second one is holding a plate — his mouth full of rice as he gazes up almost suspiciously at the third boy who is suspended in the air mid-backflip.

It’s a picture of pure joy, captured on camera by a tender and observant eye. This is the mark of JL’s photography: Deeply sensitive to the richness of humanity. His photos emanate care and respect for his subjects with an eye for intimate details.

A photo from JL’s photoset “Neverland,” shot in Baseco Beach.

The 26-year-old JL isn’t some hobbyist. His commercial works include portraits of local celebrities like Gaya sa

Pelikula darlings Ian and Paolo Pangilinan. He shot a few international faces like Riverdale heartthrob Cole Sprouse and the late Anthony Bourdain. Beyond star-studded casts, JL took photos of Filipino artists and politicians, including Kidlat Tahimik, Senator Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa, and Vice President Leni Robredo.

But JL is also a recognized photojournalist. He recently won first prize in one of six categories of the prestigious International Photography Awards for his work “Aquarium” — a scene from the Zapote Public Market in Las Piñas City.

“It was nice to see people on the beach in a pandemic. Hindi lang ‘yung feeling of taking pictures but also of just being there.” JL says about Neverland, before laughing a little. “I’m at a fucking beach, in a pandelulu.”

“It was just a quiet day ... It made me think about growing up—about being in Manila. It’s so hard to live here. It’s nice to see or share in spaces of peace that other people carve out,” he finishes.

“Sorry, what the fuck! Bakit ako naiiyak?” JL says with a laugh, wiping a tear.

But JL is also a recognized photojournalist. He recently won first prize in one of six categories of the prestigious International Photography Awards for his work “Aquarium” — a scene from the Zapote Public Market in Las Piñas City.

“It was nice to see people on the beach in a pandemic. Hindi lang ‘yung feeling of taking pictures but also of just being there.” JL says about Neverland, before laughing a little. “I’m at a fucking beach, in a pandelulu.”

“It was just a quiet day ... It made me think about growing up—about being in Manila. It’s so hard to live here. It’s nice to see or share in spaces of peace that other people carve out,” he finishes.

“Sorry, what the fuck! Bakit ako naiiyak?” JL says with a laugh, wiping a tear.

“It made me think about growing up—about being in Manila. It’s so hard to live here. It’s nice to see or share in spaces of peace that other people carve out...”

JL is an only child, the son of a flight attendant and a policeman. He graduated with a Fine Arts Degree in a graphic design-focused course while pursuing photography on the side. While he occasionally enjoys designing, JL tells me photography is a different kind of thrill.

“Hindi siya parang kapag nagde-design ka or nag-i-illustrate na you’re conjuring something from nothing,” JL says. “Photographs are already there. It’s your task to find it and that is so fun and fulfilling.”

His earliest memory of taking photography seriously was when he applied for the college newspaper’s photo staff. “Ewan ko kung anong sumapi sa akin to think na kaya ko ‘yon. Then I got in and it was validating to have people around me who kind of let me know that I was onto something,” JL recalls.

JL spent his first year of college joining photography groups, grabbing every opportunity to hone his craft. He credits his early training to Shutterpanda (now Atlas Studios), an events photography studio that covered large events like debuts and weddings.

“[Event coverage] taught me how to pay attention,” JL says. “When you’re covering events, you’re a fly on the wall… Everything unfolds around you, you just have to take photos.”

JL’s first professional project came in his second year, when he filled in for a photographer for a Young Star photoshoot. “First raket ko ‘yon,” JL recalls. “I was so nervous, kasi andoon pa si Raymond [Ang]. But I guess he liked my work because he gave me more projects and tuloy na from there.”

Raymond Ang, then editor-in-chief of Young Star, remembers their first encounter well. “A photographer we booked for a shoot cancelled the night before so we were scrambling to find a replacement,” says Raymond over email. “Since the shoot was for a story on college kids, I figured we could give someone new a chance and asked my intern for any friends who were photographers.” JL showed up the next day.

Raymond had low expectations, considering that JL was young and had no experience. “After a few snaps, I realized this kid had real talent, a real eye,” Raymond writes. “You could already see where that eye could take him. Then we just never stopped working together.”

When JL graduated, his first job was at the now defunct Rogue Magazine — a stint he calls an over-extended internship. He shadowed art director Patrick Diokno during shoots up until he was given his own assignments.

“Naalala ko ‘yung difficulty ko doon sa shift from taking portraits, to speaking to people and telling them what to do in a photo,” JL recalls. He wasn’t comfortable telling someone what to do, where to look. He didn’t know how to put them at ease.

“I would [ask the writer], “Pwede bang kausapin mo siya? Mag-usap nalang kayo, pipicturan ko nalang ‘yung nangyayari,” JL says. But he knew if he was going to become a better photographer, he had to be confident enough to make his subjects feel comfortable. So, JL learned the way he always did: Through observation.

“I followed the examples of the people around me, watching Patrick shoot, watching Raymond talk to other people,” JL says. “I really tried to absorb everything. I knew it mattered in my work.”

JL recalls a particular instance while at a shoot. He was sitting down next to stylist David Milan who commented on JL’s work. “I don’t know what was the bigger conversation but we landed on my photos … then sabi ni Milan na okay ‘yung work ko pero parang kailangan ko pang makaranas ng heartbreak.”

“I was like, why would you say that? But a few years later I understood. I won’t go into details, but around 2016 to 2019, I had a second coming of age. I got into several relationships, some break-ups, and I messed my life up so badly at some points that I thought that was it. I was also in the throes of my depression. In 2015 or 2016, doon ko nalaman na may depression pala ako.”

What changed? I asked. JL says he isn’t exactly sure, but the change felt drastic. Years in the trenches gave him a deeper sort of empathy, as if a third eye opened up to reveal a wider spectrum of emotions. It taught him what to look for and how to translate that on camera.

“I was somehow more attuned to the personness of a person,” JL says.

“Hindi siya parang kapag nagde-design ka or nag-i-illustrate na you’re conjuring something from nothing,” JL says. “Photographs are already there. It’s your task to find it and that is so fun and fulfilling.”

His earliest memory of taking photography seriously was when he applied for the college newspaper’s photo staff. “Ewan ko kung anong sumapi sa akin to think na kaya ko ‘yon. Then I got in and it was validating to have people around me who kind of let me know that I was onto something,” JL recalls.

JL spent his first year of college joining photography groups, grabbing every opportunity to hone his craft. He credits his early training to Shutterpanda (now Atlas Studios), an events photography studio that covered large events like debuts and weddings.

“[Event coverage] taught me how to pay attention,” JL says. “When you’re covering events, you’re a fly on the wall… Everything unfolds around you, you just have to take photos.”

JL’s first professional project came in his second year, when he filled in for a photographer for a Young Star photoshoot. “First raket ko ‘yon,” JL recalls. “I was so nervous, kasi andoon pa si Raymond [Ang]. But I guess he liked my work because he gave me more projects and tuloy na from there.”

Raymond Ang, then editor-in-chief of Young Star, remembers their first encounter well. “A photographer we booked for a shoot cancelled the night before so we were scrambling to find a replacement,” says Raymond over email. “Since the shoot was for a story on college kids, I figured we could give someone new a chance and asked my intern for any friends who were photographers.” JL showed up the next day.

Raymond had low expectations, considering that JL was young and had no experience. “After a few snaps, I realized this kid had real talent, a real eye,” Raymond writes. “You could already see where that eye could take him. Then we just never stopped working together.”

When JL graduated, his first job was at the now defunct Rogue Magazine — a stint he calls an over-extended internship. He shadowed art director Patrick Diokno during shoots up until he was given his own assignments.

“Naalala ko ‘yung difficulty ko doon sa shift from taking portraits, to speaking to people and telling them what to do in a photo,” JL recalls. He wasn’t comfortable telling someone what to do, where to look. He didn’t know how to put them at ease.

“I would [ask the writer], “Pwede bang kausapin mo siya? Mag-usap nalang kayo, pipicturan ko nalang ‘yung nangyayari,” JL says. But he knew if he was going to become a better photographer, he had to be confident enough to make his subjects feel comfortable. So, JL learned the way he always did: Through observation.

“I followed the examples of the people around me, watching Patrick shoot, watching Raymond talk to other people,” JL says. “I really tried to absorb everything. I knew it mattered in my work.”

JL recalls a particular instance while at a shoot. He was sitting down next to stylist David Milan who commented on JL’s work. “I don’t know what was the bigger conversation but we landed on my photos … then sabi ni Milan na okay ‘yung work ko pero parang kailangan ko pang makaranas ng heartbreak.”

“I was like, why would you say that? But a few years later I understood. I won’t go into details, but around 2016 to 2019, I had a second coming of age. I got into several relationships, some break-ups, and I messed my life up so badly at some points that I thought that was it. I was also in the throes of my depression. In 2015 or 2016, doon ko nalaman na may depression pala ako.”

What changed? I asked. JL says he isn’t exactly sure, but the change felt drastic. Years in the trenches gave him a deeper sort of empathy, as if a third eye opened up to reveal a wider spectrum of emotions. It taught him what to look for and how to translate that on camera.

“I was somehow more attuned to the personness of a person,” JL says.

︎

The next biggest shift in JL’s career was becoming staff photographer for CNN Philippines Life. At the newsroom’s infancy, features editor Don Jaucian and Raymond Ang, who was publisher at the time, decided they should take on a photographer. JL was their first choice.

“Go-to photographer na namin si JL as well kasi sobrang versatile: portraits, fashion shoots, interiors,” Don says.

One of Don’s most memorable photos by JL for CNN Philippines Life was from their coverage of preparations for the 2018 State of the Nation Address when former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (GMA) — the president who faced impeachment four times — was elected Speaker of the House, one of the highest positions in the land.

It’s a photo of GMA at the rostrum, hands cupped over her mouth as she calls out to supporters, cheering and taking photos from below. On the second level to the right is the dictator’s daughter, senator Imee Marcos who is flashing the famous “V” sign for a selfie with an attendee.

“Go-to photographer na namin si JL as well kasi sobrang versatile: portraits, fashion shoots, interiors,” Don says.

One of Don’s most memorable photos by JL for CNN Philippines Life was from their coverage of preparations for the 2018 State of the Nation Address when former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (GMA) — the president who faced impeachment four times — was elected Speaker of the House, one of the highest positions in the land.

It’s a photo of GMA at the rostrum, hands cupped over her mouth as she calls out to supporters, cheering and taking photos from below. On the second level to the right is the dictator’s daughter, senator Imee Marcos who is flashing the famous “V” sign for a selfie with an attendee.

Former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo at the 2018 State of the Nation Address as elected Speaker of the House.

Former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo at the 2018 State of the Nation Address as elected Speaker of the House.

Don observed a shift in JL’s photos in 2020. Back then, he felt JL just shot in fulfillment of an assignment. “Now, his work allowed him a bit of authority and independence over the photographs he shoots,” Don says. “I think dala na din ito ng sense na responsibility niya na maglabas ng ganitong trabaho during this difficult time in history.”

“He ended up being a photojournalist na talaga—and I think not just because of the nature of work but because he really leaned into it,” Don says. “Iba talaga yung kuha ni JL lalo na pag nasa labas siya, shooting something that documents the time that we live in.”

“Napaka-hasa nung mata ng pagkuha, ‘yung attention to the subtle details that make the photograph come alive, na hindi lang siya drama.”

He once shot portraits of women who lost husbands and sons to President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war. He accompanied writer Portia Ladrido to cover the stories of Muslims living in Maharlika Village in Taguig. Despite the risks, JL went out to cover some of the most tumultuous events in Manila during 2020. He covered the Grand Mañanita against the Anti-Terror Law, the protest decrying the ABS-CBN closure, and the Pride rally at Mendiola, capturing the exact moment police arrested twenty activists without warrant.

It’s different, he tells me, when you’re taking a photo of a celebrity versus people you’d interview on the street. Preparing for a corporate shoot is more methodical: JL wakes up early, arrives early. He prepares a list of layouts and locations when applicable.

“For the photojournalistic stories, ‘yun ‘yung may very rough images in my head of what I want na that almost never, very rarely, happen,” JL tells me. “Because when you’re out, kung ano ‘yung nandyan, ‘yun na. Gusto ko rin ‘yun. Gusto ko rin na binabato sarili ko and just seeing what I can find.”

Yet, despite everything — the International Photo Award and the years of creating fantastic work, documenting some of the most important national events — JL is reluctant to call himself a photojournalist, being genuinely afraid his photography is an act of violence against his subjects.

“I’m a privileged, [upper class] cis-man, and I’m taking these photos of people who struggle on the margins. Who am I to tell these stories?” he tells me. “Okay lang ba na ako?”

“He ended up being a photojournalist na talaga—and I think not just because of the nature of work but because he really leaned into it,” Don says. “Iba talaga yung kuha ni JL lalo na pag nasa labas siya, shooting something that documents the time that we live in.”

“Napaka-hasa nung mata ng pagkuha, ‘yung attention to the subtle details that make the photograph come alive, na hindi lang siya drama.”

He once shot portraits of women who lost husbands and sons to President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war. He accompanied writer Portia Ladrido to cover the stories of Muslims living in Maharlika Village in Taguig. Despite the risks, JL went out to cover some of the most tumultuous events in Manila during 2020. He covered the Grand Mañanita against the Anti-Terror Law, the protest decrying the ABS-CBN closure, and the Pride rally at Mendiola, capturing the exact moment police arrested twenty activists without warrant.

It’s different, he tells me, when you’re taking a photo of a celebrity versus people you’d interview on the street. Preparing for a corporate shoot is more methodical: JL wakes up early, arrives early. He prepares a list of layouts and locations when applicable.

“For the photojournalistic stories, ‘yun ‘yung may very rough images in my head of what I want na that almost never, very rarely, happen,” JL tells me. “Because when you’re out, kung ano ‘yung nandyan, ‘yun na. Gusto ko rin ‘yun. Gusto ko rin na binabato sarili ko and just seeing what I can find.”

Yet, despite everything — the International Photo Award and the years of creating fantastic work, documenting some of the most important national events — JL is reluctant to call himself a photojournalist, being genuinely afraid his photography is an act of violence against his subjects.

“I’m a privileged, [upper class] cis-man, and I’m taking these photos of people who struggle on the margins. Who am I to tell these stories?” he tells me. “Okay lang ba na ako?”

JL Javier repeatedly talks about how he hates his work. It isn’t just to deflect praise, but a deep distrust of himself and his work. JL looks at his photos and sees deficiencies. He thinks about what’s missing and what could be better.

“I always ask this question na did I exert enough, try enough? Siguro masyado ko ring kino-compare ‘yung sarili ko,” JL admits, calling it a kind of self-sabotage. “I’m just constantly comparing myself to my peers. Siguro, I don't trust my point of view enough.”

“So, do you think there needs to be a struggle to create good work?” I ask.

Yes, JL says. “You have to put in the work talaga.”

In September of this year, 2021, JL tested positive for asymptomatic Covid-19. He was one week into his home isolation when we had our first conversation. He didn’t catch it from his work on the field, he tells me.

“I felt like I successfully dodged it for so long then biglang nag-positive ako,” JL tells me. “I felt so helpless kasi wala na nga akong ginagawa at nasa bahay lang ako. Nahawa lang ako dahil may ibang tao [sa household] nagka-Covid.”

On the fourth day of his isolation, he wrote on his personal blog about how he felt punished and if he had to suffer, his suffering ought to mean something. “If I were to be trapped in this sad room with nothing but my self-pity then I may as well be productive,” he writes. “Which is why I took all these photos.”

JL’s fourteen-day quarantine came to an end when I asked him how he felt about the progress of his personal project. “Sabi ni [photographer] Geric Cruz, photography can be a way to meditate, to process,” he says. “I wanted to understand my feelings about my isolation in the language of my photos.”

“I was really hoping [to] photograph something profound or revelatory, but puro picture lang ng pusa ko, pictures of more or less the same thing because, obviously, I was confined within the same space for over two weeks.”

Even in the absence of earth-shattering revelations, JL says he didn’t emerge from isolation disappointed. It was one of the rare times he took photos for nobody but himself. “Sobrang sa akin lang ito,” says JL.

He’s referring to another point of the conversation that kept coming up: How present should a photographer be in a photograph?

“The photographer has everything to do with the photograph,” he tells me. Their personality, experiences, and history are all part of the creative practice of photography. The photograph is a space where the photographer and the subject encounter one another. With a “tacit hope that a third party, the viewer, will be able to register the traces of that previous encounter,” writes Teju Cole in his essay on portrait photography.

But what happens when you’re photographing someone you don’t like or agree with? I ask, recounting his portraits of controversial figures like Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. — namesake and son of the former dictator, who somehow has the audacity to run for president in 2022.

“Hindi ko alam kung nira-rationalize ko, pero iniisip ko kung dapat ba hinampas ko na siya noong shoot? Dapat ba binatukan ko na siya on the spot? But looking back, I did those photos for the service of a story that was bigger than mine,” he says. “‘Yung kay Bongbong, it was this moment in history na nagfa-file siya ng protest niya kay Leni [Robredo].”

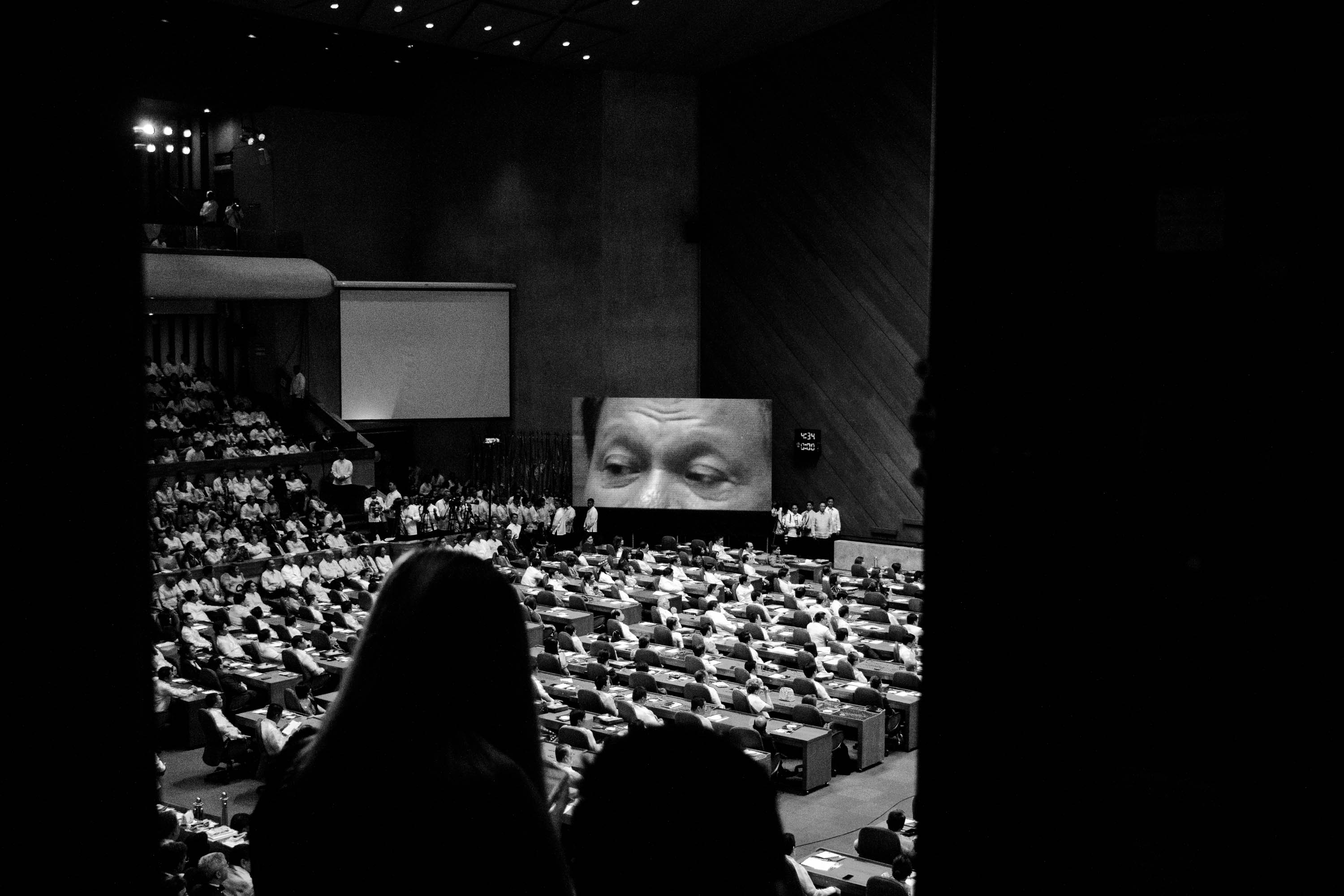

JL puts an effort into making a photograph his own, despite his self- doubt and duty to present a clear photo of one reality, wrestling it from the hands of sterile documentation. He tells me about a photo he took at the 2017 State of the Nation Address. He was stuck at Batasan, assigned to cover the event.

“I hated being there. I hated [listening] to Duterte,” JL says. He was seated in the balcony, far away from the rostrum, the center of all the action. But all of a sudden, either by mistake or design, Duterte’s eyes flashed on the projector screen, zoomed in so close you could almost make out his pores. Immediately, JL took a photo - a hall full of people as Duterte’s eyes gleaned over the crowd.

“I felt like this is both my story, my experience, and what was literally happening. I was able to frame both my story and the story that I was there to tell,” JL says.

“Siguro, that's what I’ve also been trying hard to find — the balance of how much I am going to involve myself in the photos and the story. How much do I impose my own story on the image?” he tells me.

“I believe I’ll always be present in the pictures I take. It’s just the matter of the balance of my story and the story I have to tell. Maybe there’s a way the story I want to tell is the bigger story.”

“I always ask this question na did I exert enough, try enough? Siguro masyado ko ring kino-compare ‘yung sarili ko,” JL admits, calling it a kind of self-sabotage. “I’m just constantly comparing myself to my peers. Siguro, I don't trust my point of view enough.”

“So, do you think there needs to be a struggle to create good work?” I ask.

Yes, JL says. “You have to put in the work talaga.”

In September of this year, 2021, JL tested positive for asymptomatic Covid-19. He was one week into his home isolation when we had our first conversation. He didn’t catch it from his work on the field, he tells me.

“I felt like I successfully dodged it for so long then biglang nag-positive ako,” JL tells me. “I felt so helpless kasi wala na nga akong ginagawa at nasa bahay lang ako. Nahawa lang ako dahil may ibang tao [sa household] nagka-Covid.”

On the fourth day of his isolation, he wrote on his personal blog about how he felt punished and if he had to suffer, his suffering ought to mean something. “If I were to be trapped in this sad room with nothing but my self-pity then I may as well be productive,” he writes. “Which is why I took all these photos.”

JL’s fourteen-day quarantine came to an end when I asked him how he felt about the progress of his personal project. “Sabi ni [photographer] Geric Cruz, photography can be a way to meditate, to process,” he says. “I wanted to understand my feelings about my isolation in the language of my photos.”

“I was really hoping [to] photograph something profound or revelatory, but puro picture lang ng pusa ko, pictures of more or less the same thing because, obviously, I was confined within the same space for over two weeks.”

Even in the absence of earth-shattering revelations, JL says he didn’t emerge from isolation disappointed. It was one of the rare times he took photos for nobody but himself. “Sobrang sa akin lang ito,” says JL.

He’s referring to another point of the conversation that kept coming up: How present should a photographer be in a photograph?

“The photographer has everything to do with the photograph,” he tells me. Their personality, experiences, and history are all part of the creative practice of photography. The photograph is a space where the photographer and the subject encounter one another. With a “tacit hope that a third party, the viewer, will be able to register the traces of that previous encounter,” writes Teju Cole in his essay on portrait photography.

But what happens when you’re photographing someone you don’t like or agree with? I ask, recounting his portraits of controversial figures like Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. — namesake and son of the former dictator, who somehow has the audacity to run for president in 2022.

“Hindi ko alam kung nira-rationalize ko, pero iniisip ko kung dapat ba hinampas ko na siya noong shoot? Dapat ba binatukan ko na siya on the spot? But looking back, I did those photos for the service of a story that was bigger than mine,” he says. “‘Yung kay Bongbong, it was this moment in history na nagfa-file siya ng protest niya kay Leni [Robredo].”

JL puts an effort into making a photograph his own, despite his self- doubt and duty to present a clear photo of one reality, wrestling it from the hands of sterile documentation. He tells me about a photo he took at the 2017 State of the Nation Address. He was stuck at Batasan, assigned to cover the event.

“I hated being there. I hated [listening] to Duterte,” JL says. He was seated in the balcony, far away from the rostrum, the center of all the action. But all of a sudden, either by mistake or design, Duterte’s eyes flashed on the projector screen, zoomed in so close you could almost make out his pores. Immediately, JL took a photo - a hall full of people as Duterte’s eyes gleaned over the crowd.

“I felt like this is both my story, my experience, and what was literally happening. I was able to frame both my story and the story that I was there to tell,” JL says.

“Siguro, that's what I’ve also been trying hard to find — the balance of how much I am going to involve myself in the photos and the story. How much do I impose my own story on the image?” he tells me.

“I believe I’ll always be present in the pictures I take. It’s just the matter of the balance of my story and the story I have to tell. Maybe there’s a way the story I want to tell is the bigger story.”

A projection of President Rodrigo Duterte at the

2017 State of the Nation Address.

Tina Campt, a black feminist scholar, in her book Listening to Images posits that images, particularly photographs, aren’t mute, but quiet. They solicit a form of listening and, on occasion, an investigation. Images invite the viewer to engage with the story a photo tries to tell.

“Every time I feel down or lost about my work, I look at photos of artists I admire,” citing the work of photographers Joseph Pascual, Geric Cruz, Czar Kristoff, as well as collage artist Jel Suarez.

“May mga photos na exclamation point and then may photos na ellipses,” says JL. “‘Yung work nila Joseph and Geric, they’re very powerful but so quiet, deep, and loaded. Ang yaman ng photos nila. I always strive for that.”

“Hindi ko alam kung naa-achieve ko siya. I don’t think so, pero sobrang gusto ko siyang makamit,” JL finishes.

When I get on a phone call with Geric Cruz, he tells me he’s happy about JL’s journey as a photographer. “Sobrang natutuwa ako sa trajectory niya,” he says. “Kilala ko lang siya as a portrait photographer, but when he started shooting for CNN sobrang natuwa ako. He’s fully experiencing photography.”

When I ask Geric what he means by this, he goes back to how a photographer experiences the world. Life is rich, difficult, and wonderful, and we all only get to live it once. Photographers are lucky, he says, because photographs are a way to capture and preserve a little bit of this life — an aid to memory and a chance at longevity.

“Nagsho-shoot si JL ng artista, frontliner, lahat. That’s the perfect thing na pwede mo ibigay sa isang photographer,” Geric tells me. “Nandoon ka para tumingin, nakikita mo lahat, and you experience everything.”

But a photograph is more than just an experience — it is specifically the experience of a photographer. Like any craft, photography requires practice and repetition, but a large part of it is profoundly personal. It requires perspective and intuition, an eye that can discern the images hidden from plain sight.

“Ang corny ‘man sabihin na may magic talaga,” Geric tells me. “You take a photo and you feel may kumausap sa’yo. Like it’s meant to be.”

Growing up an only child meant JL had to find ways to entertain himself and create joy through his own means. “Noong bata ako, I [drew] treasure maps for myself kasi wala akong kalaro,” JL tells me. “I would draw the map na may mga landmarks pa sa village namin.”

This is how JL describes the feeling of taking photographs outside. Left to his own devices, JL draws his own map, studies each landmark and embarks on an adventure to find the hidden treasure. Everytime he finds it — the perfect shot — words aren’t enough.

“It’s this weird and pure joy of [finding] something,” JL tells me. “It’s nothing big — just a quiet feeling of happiness, something I can call mine and maybe share with others … Anyone could have seen it pero this is my experience of it. I found this.”

“Even when I’m covering events or taking pictures of people, I think, ‘What is there to find here?’” ︎

“Every time I feel down or lost about my work, I look at photos of artists I admire,” citing the work of photographers Joseph Pascual, Geric Cruz, Czar Kristoff, as well as collage artist Jel Suarez.

“May mga photos na exclamation point and then may photos na ellipses,” says JL. “‘Yung work nila Joseph and Geric, they’re very powerful but so quiet, deep, and loaded. Ang yaman ng photos nila. I always strive for that.”

“Hindi ko alam kung naa-achieve ko siya. I don’t think so, pero sobrang gusto ko siyang makamit,” JL finishes.

When I get on a phone call with Geric Cruz, he tells me he’s happy about JL’s journey as a photographer. “Sobrang natutuwa ako sa trajectory niya,” he says. “Kilala ko lang siya as a portrait photographer, but when he started shooting for CNN sobrang natuwa ako. He’s fully experiencing photography.”

When I ask Geric what he means by this, he goes back to how a photographer experiences the world. Life is rich, difficult, and wonderful, and we all only get to live it once. Photographers are lucky, he says, because photographs are a way to capture and preserve a little bit of this life — an aid to memory and a chance at longevity.

“Nagsho-shoot si JL ng artista, frontliner, lahat. That’s the perfect thing na pwede mo ibigay sa isang photographer,” Geric tells me. “Nandoon ka para tumingin, nakikita mo lahat, and you experience everything.”

But a photograph is more than just an experience — it is specifically the experience of a photographer. Like any craft, photography requires practice and repetition, but a large part of it is profoundly personal. It requires perspective and intuition, an eye that can discern the images hidden from plain sight.

“Ang corny ‘man sabihin na may magic talaga,” Geric tells me. “You take a photo and you feel may kumausap sa’yo. Like it’s meant to be.”

Growing up an only child meant JL had to find ways to entertain himself and create joy through his own means. “Noong bata ako, I [drew] treasure maps for myself kasi wala akong kalaro,” JL tells me. “I would draw the map na may mga landmarks pa sa village namin.”

This is how JL describes the feeling of taking photographs outside. Left to his own devices, JL draws his own map, studies each landmark and embarks on an adventure to find the hidden treasure. Everytime he finds it — the perfect shot — words aren’t enough.

“It’s this weird and pure joy of [finding] something,” JL tells me. “It’s nothing big — just a quiet feeling of happiness, something I can call mine and maybe share with others … Anyone could have seen it pero this is my experience of it. I found this.”

“Even when I’m covering events or taking pictures of people, I think, ‘What is there to find here?’” ︎

Toni Potenciano is a writer and strategist for And A Half.