Out of Print

A Graphic Designer’s

Reckoning

with Race

by Jonty Cruz

Photos courtesy of Leanne Gan

For Brooklyn-based artist Leanne Gan, fulfillment came in the form of designing not for money, but for change.

Over the course of our interview, Leanne and I talk about how race has affected her life as an Asian American from discussions at home, her struggles in school, and to her work now with the American Civil Liberties Union.

“When you’re an Asian person in the context of a sea of whiteness you get so hyper focused,” Leanne says. “It got to a point where I was so anxious about everything I was doing and reading into everything people said to me. Those ‘model minority’ stuff and microaggressions seep into your psyche. It’s exhausting.”

︎

Leanne grew up in San Gabriel Valley in Los Angeles, California, which boasts one of the largest Asian American communities in the United States. She grew up surrounded by tea houses, taco trucks, and according to her, “the best Taiwanese hot pot you can ever imagine.” She had very little interest in school “but a lot of interest in KFC mashed potatoes and xiao long bao from Din Tai Fung.”

Leanne is of Filipino and Chinese descent. Her parents grew up in the same part of Manila before moving to the States, and to this day strongly identifies with the term Tsinoy. As a kid living in LA, she says she was raised with a lot more Filipino than Chinese influence. “The lechon kawali, the karaoke, and constant laughter at BBQs are a very fond memory for me and I have a lot of love for the culture I grew up with,” she says. I ask what were some of the go-to songs they’d sing at karaoke. “Celine Dion, a lot of Celine Dion,” she answers. “LeAnn Rimes and Josh Groban and my parents love Michael Bublé .” The song that everyone has sung at least once she says is Groban’s ‘You Raise Me Up’. It’s the same playlists she’d hear on the radio every time she’d visit the Philippines. That plus a certain song from One Republic that everyone seems to know. “It’s crazy! Like how is no one tired of this song yet?”

As she grew older, Leanne admits it was hard to come to terms on certain issues with her family. “I think I did really struggle with some of the conservative beliefs [they] had on gay marriage and class,” she says. She recognizes how so many issues are linked to class and how colonialism in the Philippines has affected or influenced how race is seen. “It’s very tied to the racist notion of the lighter you are the more money you’ll have.”

These are the same issues that she aims to address as a graphic designer for the ACLU. It’s a job that has come to define Leanne in some ways but also serves as validation for her and what she’s been through. “I approached my design career with the question: how do I make money?” she says. “I was a designer trying to make meaning from jobs that only cared about making money. That led to discontentment, burn out, and panic attacks caused by people who don’t care about you and only about making a profit. Working for the non-profits gave me work that I was proud of and I went to pursue that feeling.” Today Leanne works not only for the causes and issues she believes in but for those who also need help the most.

She talks more about her life growing up, her reckoning with racial discimration, and how working at the ACLU has strengthened her passion not just for design but for change.

The following was conducted via email and Zoom and has been edited for publication.

“I think when I went to college it was like you gotta get a job, you gotta get in Medicine and then I was like why do all these things? I think it inspired me to do more with my life.”

Out of Print: Hi Leanne, thanks again for agreeing to do the interview. I’m really excited to learn more about you and your work in the ACLU but before that, could you talk about life growing up? What was school like?

Leanne Gan: Hi, thanks so much for reaching out! I’ve never been an academically inclined person, which I attribute to struggling with ADHD and very little interest in academics. In some ways I’m grateful for ADHD in forcing me to pursue things that actually interested me i.e. design, rather than forcing myself to take chemistry and anatomy to make my parents happy. I did have WAY too many on-campus jobs though, which I enjoyed a lot more than actually going to classes.

For a majority of grade school, middle school, high school, my parents tried so hard to put me in a good school system. It was very intense and rigorous and the expectation was like if you had a below 4.0 GPA and didn’t have Advanced Placement classes then you’re kind of like a dummy. I had to reckon with myself being not as academically competitive and always feeling like I wasn’t as good as everyone else and being held to this standard that I couldn’t fit no matter how hard I tried.

So from a very young age it felt like it was all too hard for me and I couldn’t focus, and it would take like until 10 p.m. for me to do my homework because I couldn’t process it.

May I ask how you coped with your ADHD?

I think the nice thing about ADHD is that you can’t feign interest. Like you can’t fake being interested in something because you will lose focus instantly when it’s not interesting. Design was the first thing I felt like this is something I could focus on and that I can actively keep doing. And it all started in this screen printing class. It was this after school elective you could take. I got really, really into it and I started like a small business in school selling sweatshirts. It got me really excited because it was the first time I felt like I could do something that didn’t make me feel inadequate. It really gave me a bright hope that I would be okay after school.

Did you take up the arts in college? What was your experience and time there like?

Yeah, I ended up going to school at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington for their Physical Therapy program. After a valiant effort of trying to pass the advanced chemistry course, I dropped the major and switched to a Printmaking and Communications double major.

Tacoma was a huge culture shock to me, coming from a predominantly Asian American diaspora. In attending a very white college, I had a lot of shitty experiences with racism that included phrases like “don’t your people eat dogs,” “I’m going to call you Little China,” and a slew of other microaggressions related to Asian stereotypes.

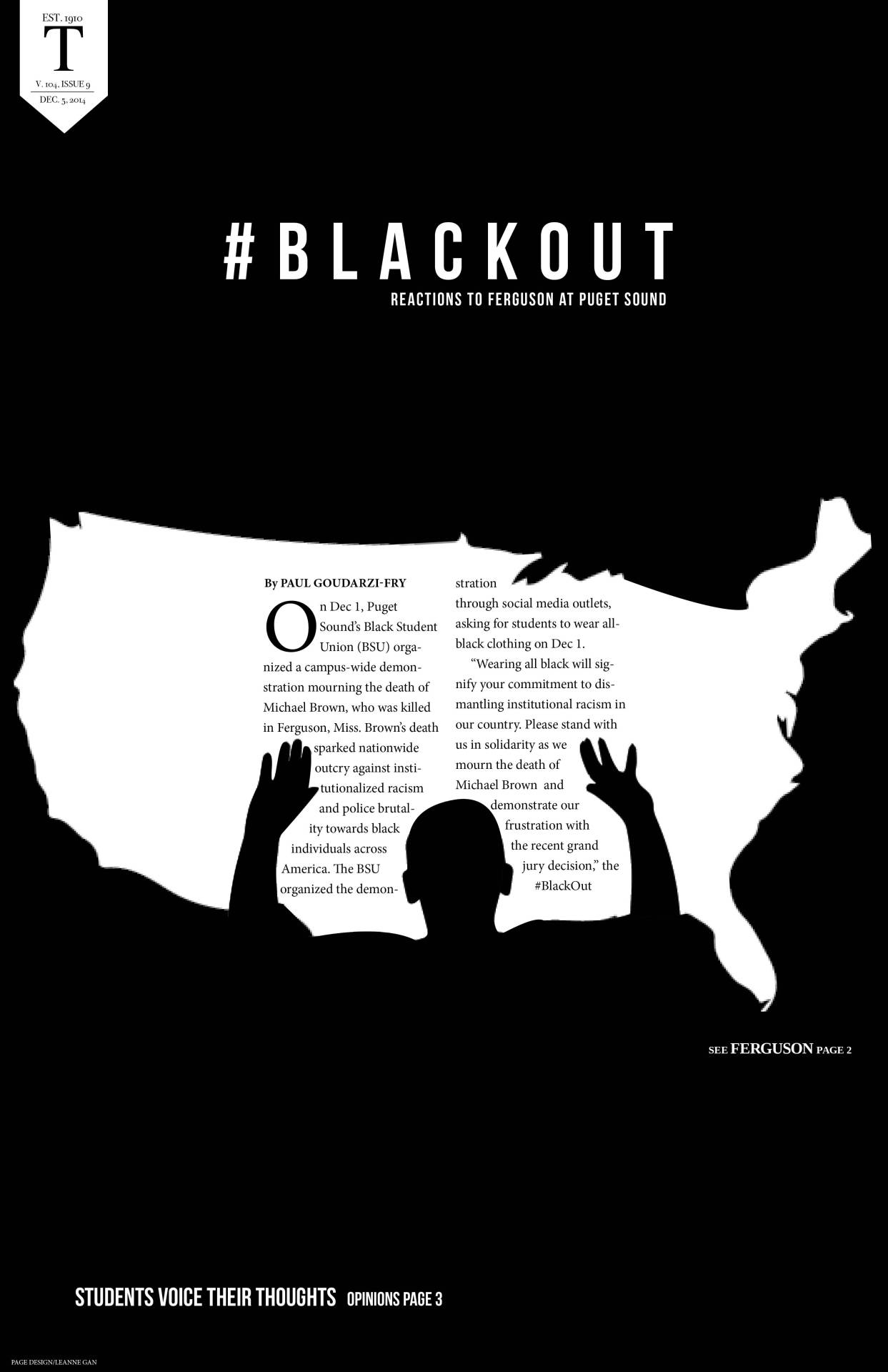

I was a sophomore when the news of Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson broke out on campus. [I was an art director] for my school newspaper at that time and I remember thinking about the pain I witnessed at vigils and protests and thinking how to create a front page cover that communicated the weight of police brutality. In that time, I realized how privileged I was to have felt protected by the police and how broken the systems of capitalism and prisons were. That reckoning shaped my interests of wanting to do more than just make money in life.

Would you mind talking about “that reckoning” more and how it shaped you?

When I say it’s a reckoning for me it’s more of [asking myself] what have I been doing? It changed what I wanted to do and what I thought was important.

I think when I went to college it was like you gotta get a job, you gotta get in Medicine and then I was like why do all these things? I think it inspired me to do more with my life. There are a lot of things wrong and I didn’t want to continue like that.

Leanne Gan: Hi, thanks so much for reaching out! I’ve never been an academically inclined person, which I attribute to struggling with ADHD and very little interest in academics. In some ways I’m grateful for ADHD in forcing me to pursue things that actually interested me i.e. design, rather than forcing myself to take chemistry and anatomy to make my parents happy. I did have WAY too many on-campus jobs though, which I enjoyed a lot more than actually going to classes.

For a majority of grade school, middle school, high school, my parents tried so hard to put me in a good school system. It was very intense and rigorous and the expectation was like if you had a below 4.0 GPA and didn’t have Advanced Placement classes then you’re kind of like a dummy. I had to reckon with myself being not as academically competitive and always feeling like I wasn’t as good as everyone else and being held to this standard that I couldn’t fit no matter how hard I tried.

So from a very young age it felt like it was all too hard for me and I couldn’t focus, and it would take like until 10 p.m. for me to do my homework because I couldn’t process it.

May I ask how you coped with your ADHD?

I think the nice thing about ADHD is that you can’t feign interest. Like you can’t fake being interested in something because you will lose focus instantly when it’s not interesting. Design was the first thing I felt like this is something I could focus on and that I can actively keep doing. And it all started in this screen printing class. It was this after school elective you could take. I got really, really into it and I started like a small business in school selling sweatshirts. It got me really excited because it was the first time I felt like I could do something that didn’t make me feel inadequate. It really gave me a bright hope that I would be okay after school.

Did you take up the arts in college? What was your experience and time there like?

Yeah, I ended up going to school at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington for their Physical Therapy program. After a valiant effort of trying to pass the advanced chemistry course, I dropped the major and switched to a Printmaking and Communications double major.

Tacoma was a huge culture shock to me, coming from a predominantly Asian American diaspora. In attending a very white college, I had a lot of shitty experiences with racism that included phrases like “don’t your people eat dogs,” “I’m going to call you Little China,” and a slew of other microaggressions related to Asian stereotypes.

I was a sophomore when the news of Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson broke out on campus. [I was an art director] for my school newspaper at that time and I remember thinking about the pain I witnessed at vigils and protests and thinking how to create a front page cover that communicated the weight of police brutality. In that time, I realized how privileged I was to have felt protected by the police and how broken the systems of capitalism and prisons were. That reckoning shaped my interests of wanting to do more than just make money in life.

Would you mind talking about “that reckoning” more and how it shaped you?

When I say it’s a reckoning for me it’s more of [asking myself] what have I been doing? It changed what I wanted to do and what I thought was important.

I think when I went to college it was like you gotta get a job, you gotta get in Medicine and then I was like why do all these things? I think it inspired me to do more with my life. There are a lot of things wrong and I didn’t want to continue like that.

Leanne’s cover for her university newspaper about the murder of Michael Brown.

Just as a tangent, I’m curious if you’ve read the book Minor Feelings?

Yes! I love it! Love it!

Your story of going into Medicine really reminded me of the idea of “the model Asian” or “the model minority” that the book talks about. Did you feel that pressure? And what are your thoughts on that idea and how that archetype was/is used to counter the protests of the African American community.

I think my issue is I’m really not a “model Asian.” I’m not good in school. I struggle with a lot of attention issues. I never got great grades. I think I had a lot of self-esteem issues that came from that. So I didn’t feel like the stereotypical Asian because I didn’t fit that stereotype. I think I also protested internally a little bit more about these model minority stereotypes because I was not that.

With assimilation, you want to distance yourself mentally from these people that you deem not as good—or whoever white people deem as not rich or not good people. It’s like what they talk about in Minor Feelings where Asian Americans align themselves with whiteness to maintain that privilege… that fake privilege.

You worked at a couple of firms and agencies before joining the ACLU. Could you share what that experience was like for you?

Sure! I worked as a creative intern after I graduated college. Outside of the generous compensation, I hated it. Corporate fashion design felt more like a formula than a process and it was a good experience in that I learned I never wanted to go this route. I moved back to LA for a family emergency and [quickly] found a job working shifts at a pie cafe in the Arts District. I also found a full-time freelance design job where I worked from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and then commuted to the pie place to work a 6-11 p.m. shift.

The freelance design job was an awful experience. My boss pitted me against this other designer to see who was faster and then fired her after a week. She positioned my screen so she could always see what I was doing, made designers sign contracts saying we could not use any of our designs at work for our portfolios, and disregarded any of my opinions with the reasoning that I was too ‘green’ or young to understand.

With two consecutive jobs and living with my parents, I built enough savings to move to New York, where I heard there were better opportunities for designers. Within the week of moving to New York, I found a job at [an agency] off of Craigslist and started work the day after my first interview. I had incredibly kind coworkers that helped me adjust to the fast paced work schedule, and I learned a lot in a very short amount of time. We were always expected to stay late for projects even though we were only being compensated for a presumed 40- hour work week. Looking for opportunities to use design to help people, I freelanced for Athlete Ally and LeAp while I worked at the agency to feel purpose in my work.

After a year of working at the agency, I was already feeling burned out and tired of using my time to make things to make hotels or tourism boards more money. I started looking for opportunities that aligned with my values and gave me a way to use design to help people. I saw the ACLU position and actually did not apply thinking I was not qualified / didn’t have a portfolio ready / thought it was too good for me. A few months later I saw the position again, and after many sessions with my therapist, decided to go for it.

Yes! I love it! Love it!

Your story of going into Medicine really reminded me of the idea of “the model Asian” or “the model minority” that the book talks about. Did you feel that pressure? And what are your thoughts on that idea and how that archetype was/is used to counter the protests of the African American community.

I think my issue is I’m really not a “model Asian.” I’m not good in school. I struggle with a lot of attention issues. I never got great grades. I think I had a lot of self-esteem issues that came from that. So I didn’t feel like the stereotypical Asian because I didn’t fit that stereotype. I think I also protested internally a little bit more about these model minority stereotypes because I was not that.

With assimilation, you want to distance yourself mentally from these people that you deem not as good—or whoever white people deem as not rich or not good people. It’s like what they talk about in Minor Feelings where Asian Americans align themselves with whiteness to maintain that privilege… that fake privilege.

You worked at a couple of firms and agencies before joining the ACLU. Could you share what that experience was like for you?

Sure! I worked as a creative intern after I graduated college. Outside of the generous compensation, I hated it. Corporate fashion design felt more like a formula than a process and it was a good experience in that I learned I never wanted to go this route. I moved back to LA for a family emergency and [quickly] found a job working shifts at a pie cafe in the Arts District. I also found a full-time freelance design job where I worked from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and then commuted to the pie place to work a 6-11 p.m. shift.

The freelance design job was an awful experience. My boss pitted me against this other designer to see who was faster and then fired her after a week. She positioned my screen so she could always see what I was doing, made designers sign contracts saying we could not use any of our designs at work for our portfolios, and disregarded any of my opinions with the reasoning that I was too ‘green’ or young to understand.

With two consecutive jobs and living with my parents, I built enough savings to move to New York, where I heard there were better opportunities for designers. Within the week of moving to New York, I found a job at [an agency] off of Craigslist and started work the day after my first interview. I had incredibly kind coworkers that helped me adjust to the fast paced work schedule, and I learned a lot in a very short amount of time. We were always expected to stay late for projects even though we were only being compensated for a presumed 40- hour work week. Looking for opportunities to use design to help people, I freelanced for Athlete Ally and LeAp while I worked at the agency to feel purpose in my work.

After a year of working at the agency, I was already feeling burned out and tired of using my time to make things to make hotels or tourism boards more money. I started looking for opportunities that aligned with my values and gave me a way to use design to help people. I saw the ACLU position and actually did not apply thinking I was not qualified / didn’t have a portfolio ready / thought it was too good for me. A few months later I saw the position again, and after many sessions with my therapist, decided to go for it.

“I think artists and designers have a unique set of skills that can help a community.”

Was there a moment or moments that led you to decide to join the ACLU?

Mike Brown’s murder in Ferguson, the constant attack of Black folks before and after Ferguson, Trump being elected into office, and my feeling powerless, a therapy session after consecutive panic attacks, [all] prompted me to make changes in my life.

What’s been the experience like so far with the ACLU?

It’s honestly been a dream. I have an incredible team of coworkers that are all motivated by the same goals. They are supportive of everything I put out and I owe a lot of my confidence in design to their encouragement.

In your own words what does the ACLU do and how do you contribute to that work or help push their goals forward?

The ACLU fights for everyone’s civil rights and works to expand those rights in the courts and minds of the public. As a designer, I get to help convey those issues visually in call to actions, protest posters, educational flyers, and more. It’s a really fun job but at times can feel tiring if there’s a barrage of bad news we’re responding to.

The ACLU handles a lot of really important and multifaceted issues and cases. What’s it been like to sort of translate all that through design?

When I design things today that convey what’s going on right now my goal usually is not to change anyone’s mind per se but to capture what’s currently happening and to also capture the feeling right. There’s a lot of intention and a lot of thinking that goes behind what you put in your composition: what does it symbolize, where do you want it to go, and how do you want people to look back on it? I want to accurately communicate what the feeling is and what the purpose is.

There is an element of restraint. The ACLU comes at it from a legal perspective and what they want is more reform than revolution if that makes sense, so I have to bring it down from where I’d like it to go at times.

What is it we want our audience to know and get behind, if there’s certain policies we want to share or what we want to change or vote on? I think that’s the incremental change we’re talking about. A lot of design for me is how do you condense complicated thoughts into one easy to get composition.

What projects have stood out for you during your time in ACLU?

There are two that really stand out to me. One was a campaign leading up to the October 8 Supreme Court arguments that decided if people could be fired for being LGBTQ with the ACLU representing Aimee Stephens and Don Zarda. I did the protest posters, the banners, and social posts leading up to this event. I got to attend the rally in front of the Supreme Court and got to chat with Aimee after the arguments which was very special to me. She passed away before hearing the decision, but she left behind an incredible win for trans people in the workplace.

The second was designing the ‘Divesting from police. Defending our protest rights.’ blog the week after the George Floyd protests began. I was so filled with rage and helplessness and it gave me some comfort to work on something that positively contributed to the chaos around me.

You worked on the ACLU’s obituary and tribute to Ruth Bader Ginsberg. What was that experience like for you and how would you describe her impact not just for Americans but women and the world?

It was a lot of pressure to design this tribute, as she’s a huge figure both to the ACLU and the country as a whole. It felt surreal when I made it and it still does after it was printed. While I don’t agree with all of her stances, I am very grateful for the many contributions she made to forward women’s rights.

Mike Brown’s murder in Ferguson, the constant attack of Black folks before and after Ferguson, Trump being elected into office, and my feeling powerless, a therapy session after consecutive panic attacks, [all] prompted me to make changes in my life.

What’s been the experience like so far with the ACLU?

It’s honestly been a dream. I have an incredible team of coworkers that are all motivated by the same goals. They are supportive of everything I put out and I owe a lot of my confidence in design to their encouragement.

In your own words what does the ACLU do and how do you contribute to that work or help push their goals forward?

The ACLU fights for everyone’s civil rights and works to expand those rights in the courts and minds of the public. As a designer, I get to help convey those issues visually in call to actions, protest posters, educational flyers, and more. It’s a really fun job but at times can feel tiring if there’s a barrage of bad news we’re responding to.

The ACLU handles a lot of really important and multifaceted issues and cases. What’s it been like to sort of translate all that through design?

When I design things today that convey what’s going on right now my goal usually is not to change anyone’s mind per se but to capture what’s currently happening and to also capture the feeling right. There’s a lot of intention and a lot of thinking that goes behind what you put in your composition: what does it symbolize, where do you want it to go, and how do you want people to look back on it? I want to accurately communicate what the feeling is and what the purpose is.

There is an element of restraint. The ACLU comes at it from a legal perspective and what they want is more reform than revolution if that makes sense, so I have to bring it down from where I’d like it to go at times.

What is it we want our audience to know and get behind, if there’s certain policies we want to share or what we want to change or vote on? I think that’s the incremental change we’re talking about. A lot of design for me is how do you condense complicated thoughts into one easy to get composition.

What projects have stood out for you during your time in ACLU?

There are two that really stand out to me. One was a campaign leading up to the October 8 Supreme Court arguments that decided if people could be fired for being LGBTQ with the ACLU representing Aimee Stephens and Don Zarda. I did the protest posters, the banners, and social posts leading up to this event. I got to attend the rally in front of the Supreme Court and got to chat with Aimee after the arguments which was very special to me. She passed away before hearing the decision, but she left behind an incredible win for trans people in the workplace.

The second was designing the ‘Divesting from police. Defending our protest rights.’ blog the week after the George Floyd protests began. I was so filled with rage and helplessness and it gave me some comfort to work on something that positively contributed to the chaos around me.

You worked on the ACLU’s obituary and tribute to Ruth Bader Ginsberg. What was that experience like for you and how would you describe her impact not just for Americans but women and the world?

It was a lot of pressure to design this tribute, as she’s a huge figure both to the ACLU and the country as a whole. It felt surreal when I made it and it still does after it was printed. While I don’t agree with all of her stances, I am very grateful for the many contributions she made to forward women’s rights.

Leanne’s “Trans People Belong” ACLU poster. Photo is from a Supreme Courty rally which she got to attend.

Leanne’s “Trans People Belong” ACLU poster. Photo is from a Supreme Courty rally which she got to attend.In recent years and especially these last several months, we’ve seen graphic designers take to Instagram and social media to push causes that matter to them. As someone who does this professionally and personally, why do you think this is an important role for graphic designers and artists and what do you think needs to be done more?

I think artists and designers have a unique set of skills that can help a community. As a designer that notices and integrates visual trends, there are a lot of opportunities to push out vital information or ideas in a way that people will notice and want to share. I don’t believe in artists that don’t want to do anything political, because doing nothing means something.

Would you say that design is a good trojan horse to get information out there?

Yeah, absolutely! I’m excited to talk about this. Design [right now] is using a ton of trends like streetwear, corporate branding, or even memes to take this very popular method of sharing things and then add very important political messaging to the subtext. It’s fun to consume. It’s fast. It’s really cool because it’s such a beautiful intersection of design and information.

I think there is a danger too, especially in social media and sharing things too much. There’s burnout. There used to be a time when people just went on social media to escape but now there’s this concept of who can escape and who can choose not to see certain content. But also I think there’s a danger in this fast quick little format of like “everything you need to know about racial justice in six slides” but you really can’t sum up everything. It leads people to believe they now know everything they need to know and don’t have to go deeper into it or don’t have to do the research. There is some danger in thinking that’s enough or just having people participate in social media and not being on the ground. So personally, I try to do what I can as a designer and go out to support the communities around me.

You also contributed work to Merch Aid in support of Cubbyhole. From how you describe the bar, it sounds so special to you. Could you talk about how it serves as a safe and memorable space for you?

I LOVE the Cubbyhole. You know how some people have that one bar, where you know the bartender and know how many minutes it would take to walk over there from work? That’s my spot. I’ve had so many first dates and birthdays there and the people are just lovely. When I used to get back from trips, I’d always want to swing by the Cubbyhole as a part of my “I’m back home” ritual.

Between your work for ACLU and Merch AId, you’ve found for yourself a way for graphic design to be a tool for community building. Why is that important and what else do you hope to do for others and social causes as a graphic designer and artist?

Designing for change, for a small bar that I wanted to support, and for campaigns that improve people's lives has brought me so much joy. I hope people find ways to support their own communities in ways that make them feel joy.

It seems the places you’ve spent in your life from LA to Tacoma and now in Brooklyn have left an impression on you. Could you talk about what living in Brooklyn / New York has done for you?

Moving to New York has been really nice. I feel like I’m not as hyper focused on my own race because I’m surrounded by other people from different cultures. It doesn’t feel like it’s focused on me being in a room with 10 other white people, like it did in Tacoma.

Do you feel like you’re most like yourself now living in New York?

Absolutely. You just meet so many different types of people and have so many opportunities to truly surround yourself with people you feel comfortable with. There are so many different types of spaces for different people. I really love hanging out in queer spaces and those spaces that really value community.

There are things like Queer Soup Night that I think are super cute where this lady named Liz [Alpern] would get three queer chefs to make three different types of soups and everyone comes in to buy and all the proceeds go to a different non-profit every event. It’s really cute to just drink soup with a bunch of other queers.

I can’t thank you enough for sharing your story, Leanne! I guess my last question would be if you’d consider working in the ACLU as your greatest success to date?

I think my greatest success is getting out of the corporate agency world and getting to use my design skills to help people. Community focused design has taught me so much about people and motivates me to get involved in helping out in whatever capacity I can.︎

I think artists and designers have a unique set of skills that can help a community. As a designer that notices and integrates visual trends, there are a lot of opportunities to push out vital information or ideas in a way that people will notice and want to share. I don’t believe in artists that don’t want to do anything political, because doing nothing means something.

Would you say that design is a good trojan horse to get information out there?

Yeah, absolutely! I’m excited to talk about this. Design [right now] is using a ton of trends like streetwear, corporate branding, or even memes to take this very popular method of sharing things and then add very important political messaging to the subtext. It’s fun to consume. It’s fast. It’s really cool because it’s such a beautiful intersection of design and information.

I think there is a danger too, especially in social media and sharing things too much. There’s burnout. There used to be a time when people just went on social media to escape but now there’s this concept of who can escape and who can choose not to see certain content. But also I think there’s a danger in this fast quick little format of like “everything you need to know about racial justice in six slides” but you really can’t sum up everything. It leads people to believe they now know everything they need to know and don’t have to go deeper into it or don’t have to do the research. There is some danger in thinking that’s enough or just having people participate in social media and not being on the ground. So personally, I try to do what I can as a designer and go out to support the communities around me.

You also contributed work to Merch Aid in support of Cubbyhole. From how you describe the bar, it sounds so special to you. Could you talk about how it serves as a safe and memorable space for you?

I LOVE the Cubbyhole. You know how some people have that one bar, where you know the bartender and know how many minutes it would take to walk over there from work? That’s my spot. I’ve had so many first dates and birthdays there and the people are just lovely. When I used to get back from trips, I’d always want to swing by the Cubbyhole as a part of my “I’m back home” ritual.

Between your work for ACLU and Merch AId, you’ve found for yourself a way for graphic design to be a tool for community building. Why is that important and what else do you hope to do for others and social causes as a graphic designer and artist?

Designing for change, for a small bar that I wanted to support, and for campaigns that improve people's lives has brought me so much joy. I hope people find ways to support their own communities in ways that make them feel joy.

It seems the places you’ve spent in your life from LA to Tacoma and now in Brooklyn have left an impression on you. Could you talk about what living in Brooklyn / New York has done for you?

Moving to New York has been really nice. I feel like I’m not as hyper focused on my own race because I’m surrounded by other people from different cultures. It doesn’t feel like it’s focused on me being in a room with 10 other white people, like it did in Tacoma.

Do you feel like you’re most like yourself now living in New York?

Absolutely. You just meet so many different types of people and have so many opportunities to truly surround yourself with people you feel comfortable with. There are so many different types of spaces for different people. I really love hanging out in queer spaces and those spaces that really value community.

There are things like Queer Soup Night that I think are super cute where this lady named Liz [Alpern] would get three queer chefs to make three different types of soups and everyone comes in to buy and all the proceeds go to a different non-profit every event. It’s really cute to just drink soup with a bunch of other queers.

I can’t thank you enough for sharing your story, Leanne! I guess my last question would be if you’d consider working in the ACLU as your greatest success to date?

I think my greatest success is getting out of the corporate agency world and getting to use my design skills to help people. Community focused design has taught me so much about people and motivates me to get involved in helping out in whatever capacity I can.︎

Jonty Cruz is a writer and creative consultant based in Manila.