Out of Print

Melissa Miranda Wants to Build a Movement

by Liz Yap

Photos courtesy of Melissa Miranda.

Portraits by Andrew Imanaka.

The Filipinx-American owner of Musang in Seattle, Washington talks about identity, contributing to Bon Appetit, and why her success needs to be inclusive.

Musang was a dream years in the making, though Melissa took a circuitous journey to get there. Born and raised in Seattle to Filipinx immigrants, she grew up surrounded by a large extended family and the many traditions that came with it—and of course, the food. Melissa affectionately recalls many childhood afternoons spent watching her dad make adobong pusit, sarciado, paksiw, pinakbet. A detour to Italy for culinary school, however, meant that she initially considered opening an Italian restaurant. But she soon realized that wherever life took her—whether she was studying in Florence or hustling as a chef in New York—she’d find herself cooking Filipinx food whenever she was homesick. Spurred by a growing curiosity and a desire to strengthen her connection to her heritage, she began traveling back home to the Philippines every year. She’d stay for months or weeks at a time, renting an apartment in Mandaluyong, and reconnecting with friends, family, and family of friends—gaining a more profound understanding of the food, the culture, and what it meant to be Filipinx along the way.

“I think I always wanted to cook Filipinx food, but I didn’t think that we could because we were never given much space for it,” she says. Coming back to Seattle after years spent away from her hometown, she started asking herself why she’d spent most of her culinary career cooking everyone else’s food but her own. “It was so important for me to realize that, wait, Mel, you don’t have to cook Italian food. You don’t have to cook Asian, Korean, or French food. You can cook your own food and tell your own story. It was that moment of looking around and not seeing what I wanted represented here. Then it became really important to me to find a way to share that.”

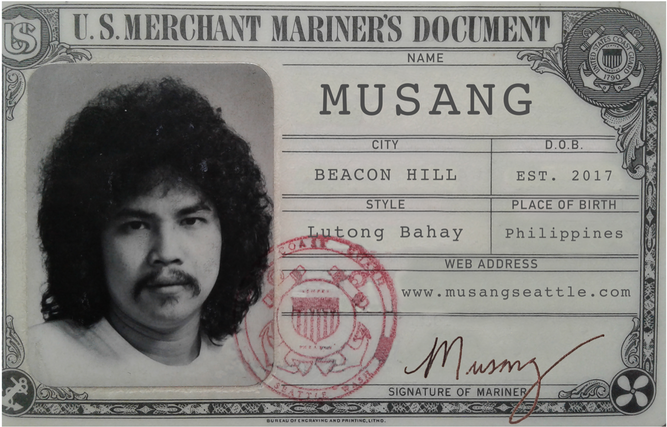

Musang, named after Melissa’s dad, began as a series of pop-ups that ran for years. When it was time to build a brick-and-mortar restaurant, they turned to their community for support, raising $91,000 through a wildly successful Kickstarter campaign and receiving a grant from the city. They found a beautiful old Craftsman home in Beacon Hill to turn into a place of their own. “When you walk into the restaurant, it feels like you’re going to your lola’s house. There’s art done by Filipinx-Americans here, little touches that remind you of home. It feels elegant but still homey, which is the goal for us.”

Now here was the dream, fully realized. Then, as every story in 2020 goes: the pandemic hit. In March, as COVID-19 began to spread in the U.S., Melissa knew she had to put the safety of her team and their community first, and made the difficult decision to shut down even before any official city or state mandates. Grappling with grief and wondering about the future of the restaurant they had worked so hard to build, she decided to turn her anguish into action. Melissa and her sous chef Jonnah Ayala transformed Musang into a community kitchen, making the commitment to cook for food-insecure families and those in need. For months, they operated seven days a week, providing 200 meals a day—a community effort that was completely donation-based.

However difficult navigating the pandemic has been, Melissa says it has given them a lot of time to reflect on how they want to show up, how to take care of their community, and how to eventually change the business model of this industry. Community-driven, not chef-driven, is how she describes what they do. She’s building a different kind of restaurant, one that abandons the toxic structures and systems prevalent in the industry for a workplace that feels closer to a family, one that truly takes care of its people and puts them front and center. She is fervent in her belief that Musang can be more than just a restaurant, that it can be a community space, maybe even a movement. It’s clear that food is just one avenue through which she finds opportunities to bring people together and effectively drive change.

As Seattle started opening up again in late 2020, Musang began doing takeout but kept the community kitchen in operation. At the end of the year, they were awarded Best Restaurant of the Year by Seattle Met. Being on the cover of the magazine meant something deeper to her as well: “My nieces got to see a brown Filipinx woman in her tattooed glory on a magazine cover, and that’s inspiring. I never saw that, because that wasn’t the standard of beauty for Filipinxs when I was growing up. It’s been an inspiring journey, because it’s more than the food. It’s about highlighting our stories, giving back, and inspiring the next generation of what we’re capable of.”

Here, Melissa talks about growing up Filipinx-American, joining Bon Appetit as a contributor, and why she really hates the word chef.

The following was conducted over Zoom and has been edited for publication.

“Especially within our culture, there’s certain expectations of how we need to act. You’re supposed to be quiet, you’re not supposed to take up so much space. No tattoos.”

Liz Yap: Hi Melissa! Thank you so much for talking to me today. You had a long and colorful journey before you opened Musang. Did you always know that you wanted to cook for a living?

Melissa Miranda: No. [Laughs.] I actually went to the University of Washington and I have a degree in sociology. I thought I was going to get into social work, but in college I started working in the front of house as a hostess, as a server. I met a lot of really incredible people that I never would have met in regular life. It opened my eyes to this different kind of education that can exist that’s not just academic: through people, through communication, through friendship. I was inspired by one of my co-workers to study abroad in Italy when I was in college, and I fell in love with the culture and the food. When I graduated, I worked for a couple of years but there was something missing. So I found myself back in Florence. I taught English and I found a culinary school. I talked to my parents and I said, this is where I’m thinking I’m going, I know it’s not like a doctor or an engineer or what you had hoped for me to be, but I hope you can support me because this is something I’m so passionate about. Growing up, I really loved cooking. And then when I started culinary school, it just clicked and I felt this is where I needed to be, this is where my passion lies.

What did you end up doing after culinary school?

I stayed in Florence for five years. I cooked in a lot of different restaurants there, learned the language, started developing my philosophy of how I wanted to approach food. It was about freshness, seasonality, using what’s available to come up with flavors that are reminiscent of our culture and food. I have a friend named Romina who’s Filipinx-Italian, and we would play around with dishes. We’d add artichoke hearts to our kare-kare, sometimes we’d make adobo with grapes and red wine. It was fun to adapt to where we were to try and cook the food that we knew.

After my time in Italy, I ended up moving to New York. I had the opportunity to open a restaurant in Brooklyn, I went corporate, I worked as a sous chef for a friend of mine from Seattle. I did my first pop-up with Maharlika, which was a really cool experience. What I learned in New York was the hustle. I had to think outside the box and quickly learn management skills because most of the people on my team were male. As a woman and a woman of color, how do you assert yourself, how do you communicate well, how do you gain people’s trust?

After a few years in New York, I felt really homesick, because I’m so close to my family. I felt it was time to come back to Seattle. I came back thinking I was going to open an Italian restaurant, but obviously Italian food is very saturated here. One day, I was driving down the neighborhood my dad first immigrated to, Beacon Hill. It was a historically Filipinx neighborhood that had Filipinx restaurants and they had all closed. So I was inspired to start doing Filipinx pop-ups. Every month, the menu would change. We wanted to give people more of an idea of what Filipinx food was beyond chicken adobo, pancit, and lumpia—to educate people that there’s so many more ingredients and dishes to it.

What was the reaction like?

People started getting really excited. We built this word-of-mouth following and sold out of every pop-up that we had. There were a lot of younger Filipinxs bringing their parents, a lot of older Filipinxs being so proud and excited to see their food represented in a way that wasn’t the usual turo-turo.

Our food is based on what we can find that’s in season. For example, in the restaurant now, we’re doing spring laing but with pea vines and coconut cream, which is very different for some of the older Filipinxs that come in here, but they love the idea that it’s very fresh, very local. And that’s how the theme worked with the pop-ups in the beginning. It might not look like a traditional Filipinx dish that you would see, but when you taste it, you’d have that Ratatouille moment because the flavors were still there. I think that really set us apart.

Melissa Miranda: No. [Laughs.] I actually went to the University of Washington and I have a degree in sociology. I thought I was going to get into social work, but in college I started working in the front of house as a hostess, as a server. I met a lot of really incredible people that I never would have met in regular life. It opened my eyes to this different kind of education that can exist that’s not just academic: through people, through communication, through friendship. I was inspired by one of my co-workers to study abroad in Italy when I was in college, and I fell in love with the culture and the food. When I graduated, I worked for a couple of years but there was something missing. So I found myself back in Florence. I taught English and I found a culinary school. I talked to my parents and I said, this is where I’m thinking I’m going, I know it’s not like a doctor or an engineer or what you had hoped for me to be, but I hope you can support me because this is something I’m so passionate about. Growing up, I really loved cooking. And then when I started culinary school, it just clicked and I felt this is where I needed to be, this is where my passion lies.

What did you end up doing after culinary school?

I stayed in Florence for five years. I cooked in a lot of different restaurants there, learned the language, started developing my philosophy of how I wanted to approach food. It was about freshness, seasonality, using what’s available to come up with flavors that are reminiscent of our culture and food. I have a friend named Romina who’s Filipinx-Italian, and we would play around with dishes. We’d add artichoke hearts to our kare-kare, sometimes we’d make adobo with grapes and red wine. It was fun to adapt to where we were to try and cook the food that we knew.

After my time in Italy, I ended up moving to New York. I had the opportunity to open a restaurant in Brooklyn, I went corporate, I worked as a sous chef for a friend of mine from Seattle. I did my first pop-up with Maharlika, which was a really cool experience. What I learned in New York was the hustle. I had to think outside the box and quickly learn management skills because most of the people on my team were male. As a woman and a woman of color, how do you assert yourself, how do you communicate well, how do you gain people’s trust?

After a few years in New York, I felt really homesick, because I’m so close to my family. I felt it was time to come back to Seattle. I came back thinking I was going to open an Italian restaurant, but obviously Italian food is very saturated here. One day, I was driving down the neighborhood my dad first immigrated to, Beacon Hill. It was a historically Filipinx neighborhood that had Filipinx restaurants and they had all closed. So I was inspired to start doing Filipinx pop-ups. Every month, the menu would change. We wanted to give people more of an idea of what Filipinx food was beyond chicken adobo, pancit, and lumpia—to educate people that there’s so many more ingredients and dishes to it.

What was the reaction like?

People started getting really excited. We built this word-of-mouth following and sold out of every pop-up that we had. There were a lot of younger Filipinxs bringing their parents, a lot of older Filipinxs being so proud and excited to see their food represented in a way that wasn’t the usual turo-turo.

Our food is based on what we can find that’s in season. For example, in the restaurant now, we’re doing spring laing but with pea vines and coconut cream, which is very different for some of the older Filipinxs that come in here, but they love the idea that it’s very fresh, very local. And that’s how the theme worked with the pop-ups in the beginning. It might not look like a traditional Filipinx dish that you would see, but when you taste it, you’d have that Ratatouille moment because the flavors were still there. I think that really set us apart.

You often emphasize that Musang is community-driven, not chef-driven. Can you share more about what that means to you?

Oftentimes, in this industry, you only know the name of the chef, but you don’t know the faces of the people behind it. For me, it’s not about my story, it’s not about my food. It’s about our food. The way we build menus is together as a team. Everyone has an opinion, everyone has something to say. It’s important to me that they get to develop the skills necessary to become a good leader so that maybe one day when they open up their own restaurant, they can do it in a different way. It’s not just about one voice, it’s about all our voices—how we represent our community and how we serve, how we feed people, how we curate experiences here. It’s not about me wanting the credit; absolutely not, I would rather be hiding behind the curtain. But I also know the platform I now have means making sure I can create a sustainable future for my people and hopefully the next generation too, and creating more opportunities because that’s what we need here.

Was this always something that you had envisioned doing when you were given the opportunity to strike out on your own? Was it based on your own experiences in other restaurant kitchens?

What a lot of my restaurant experiences taught me were the ways I didn’t want to operate. I saw a lot of racism, a lot of misogyny, a lot of sexism. That kitchen and restaurant culture can be very toxic. I experienced a lot of that. When I started doing my pop-ups, I saw that there could be a different way. I’ve had some great mentors and I’ve tried to model them in how they’d lead their teams. When I opened Musang, I made a conscious and intentional decision to do it my way and just try it. The investment in growth within my whole team has paid off and there’s a sense of camaraderie that’s developed. It has been really incredible to see over this past year. There’s some cooks with so much trauma from places they were at before, that when they came here, it felt so strange for them to be treated with respect and treated as an equal. But now that they’ve experienced the benefits of it, it’s been so beautiful.

Oftentimes, in this industry, you only know the name of the chef, but you don’t know the faces of the people behind it. For me, it’s not about my story, it’s not about my food. It’s about our food. The way we build menus is together as a team. Everyone has an opinion, everyone has something to say. It’s important to me that they get to develop the skills necessary to become a good leader so that maybe one day when they open up their own restaurant, they can do it in a different way. It’s not just about one voice, it’s about all our voices—how we represent our community and how we serve, how we feed people, how we curate experiences here. It’s not about me wanting the credit; absolutely not, I would rather be hiding behind the curtain. But I also know the platform I now have means making sure I can create a sustainable future for my people and hopefully the next generation too, and creating more opportunities because that’s what we need here.

Was this always something that you had envisioned doing when you were given the opportunity to strike out on your own? Was it based on your own experiences in other restaurant kitchens?

What a lot of my restaurant experiences taught me were the ways I didn’t want to operate. I saw a lot of racism, a lot of misogyny, a lot of sexism. That kitchen and restaurant culture can be very toxic. I experienced a lot of that. When I started doing my pop-ups, I saw that there could be a different way. I’ve had some great mentors and I’ve tried to model them in how they’d lead their teams. When I opened Musang, I made a conscious and intentional decision to do it my way and just try it. The investment in growth within my whole team has paid off and there’s a sense of camaraderie that’s developed. It has been really incredible to see over this past year. There’s some cooks with so much trauma from places they were at before, that when they came here, it felt so strange for them to be treated with respect and treated as an equal. But now that they’ve experienced the benefits of it, it’s been so beautiful.

You recently joined Bon Appetit as a contributor after they rebooted their video programming slate. How did the opportunity come about?

Marcus Samuelsson had a show called No Passport Required and he came to Seattle to film an episode here. I was put in touch with his producers and I took this position of showing him that there is incredible Filipinx food in Seattle and an incredibly stronger Filipinx community. A lot of my good friends own restaurants and cafes here—there’s a famous bakeshop, there’s Archipelago, there’s Barkada—and they’re all young, driven, Filipinx individuals trying to take up space for our food. So he filmed an episode here and it was beautiful. It showed the faces of our community, the different ways we’re approaching Filipinx food.

Marcus and I were able to make a strong connection, because he really believed in what I was doing and saw the community-building aspect in it. We would check in on each other, he’d check in on the progress of building the restaurant. And then he was named the global ambassador of Bon Appetit when they had the relaunch with Dawn [Davis] and Sonia [Chopra]. He emailed me and he said, I think you would be a really great fit for what we’re trying to do.

And it was a difficult decision. I was reading all about the inequalities that were happening at Bon Appetit, and there’s that fear of... you don’t want to just be another brown face that is being used for your story. I’m also hugely shy, or I can get really nervous, but I also know that I can be very relatable and it’s a very authentic version of who I am and I’m coming to terms with that. I can’t hide in the kitchen anymore.

But you’re such a natural in front of the camera.

That’s funny. If you’d seen the videos I did earlier on, I was terrible. But one of my best friends, Elmer, he’s my assistant for the videos. He’s always in the background, telling me to smile or to laugh. It makes it easier.

It takes practice, I guess.

I think so, just being comfortable with who you are. So I went through the interview process and I was very frank, asking all these questions. How are we being paid? Will I have direction over what recipes I get to share? I don’t want to be just this Filipinx who’s being used for her story. And they’ve been very supportive. The first two episodes came out and it was kind of like a trial. But I feel being able to see the words adobong pusit pancit on Bon Appetit and it’s not, like, squid ink pasta, it means so much. Ginataang alamasag—like, what the fuck? I can’t believe it. What it means to our people, you know? That our food can look beautiful. Our food can be represented and showcased. That was what made me decide to be in Bon Appetit. It’s not for fame because I definitely want to shy away from that. It’s more about being able to have a platform to share our food, for people to be proud of our food, to not be ashamed of our food, to stop putting Western cultures and other cuisines before our food. And that’s been a huge driving factor in what I’ve been sharing and how I’ve been sharing it.

I really appreciate the way that Bon Appetit has captured me. Some of the videos are really funny. They’re quirky and I’m awkward and my personality really comes out. I’m so glad that they kept that. I’m not molding myself to be a TV personality. You’re just there and you’re hanging out with me as we would. People who know me and have seen the videos love it because it’s me. The reach is great and it’s been very inspiring. I’m getting messages now from people in the Philippines, young Filipinx cooks that are just so proud. It’s mind-blowing for me. I think I’m still processing it all.

I thought the chicken afritada video was so lovely because you were tearing up at the end, plating it and talking about your lola.

A rollercoaster of emotions!

But it’s wonderful to see you representing yourself so authentically.

Thank you. In your younger years, I feel like you’re always trying to prove something. That might have just been me, but especially within our culture, there’s certain expectations of how we need to act. You’re supposed to be quiet, you’re not supposed to take up so much space. No tattoos.

Dalagang Pilipina.

When I was younger, I was more quiet, less outspoken. For now, I’m embracing my whole self. I’ve had some really beautiful, strong women in my life that have inspired me, too. And I’ve done a lot of work with therapy and self-growth within that, which is also very taboo in our culture, but I also advocate that with my team. To be able to connect to people, you have to accept that you need to be vulnerable, and that’s very difficult. But in that vulnerability, your true, honest, authentic self comes out. With the Bon Appetit videos, I’ve just accepted that I’m really dorky, or I’ll make funny jokes, and that’s okay because that’s who I am.

So ultimately, has your experience with BA been positive so far? Are you happy you decided to go for it?

I am, and it comes with the weight, too. You put yourself in a vulnerable position to be criticized. But I realized that the impact of me being on Bon Appetit would be far greater than the criticisms. Just being able to have that platform to see our names on the screen like that, to be able to share stories and share ingredients, knowing that a lot of people now have these Filipinx pantry staples in their house makes me very excited.

Like Knorr seasoning. Gotta have that Knorr.

Yes! Or Silver Swan, or Datu Puti. And people are doing it. People are making these dishes, you know. I never thought the rich white lady across the street would be making this food but she is, and that’s a win in my book.

Melissa with her Musang team.

You cook with so much joy, and you have such a joyful presence. When I watch your videos, it’s so lighthearted and I really feel the love you put into what you make. I was wondering if that’s your overall approach to cooking.

Thank you. I think it is. For me, how I approach food and how I want my team to approach food is: how are they connected to this dish? Does it speak to them? Are they excited about it? Because it’s not just about me putting a dish on the menu, it’s about them putting a dish on the menu. At the end of the day, all of us are just here to nourish people. We’ve had people come in here and cry because the food makes them remember a moment in their childhood and they’re so moved by it. All of us here are just trying to make something that can connect in a way that is far more important than the name attached to it.

I really hate the word “chef.” I really, truly do. There’s so much trauma for me that comes with the word chef. It makes me think of toxic masculinity and white male culture. I know it’s a form of respect, but I think in some ways it gets lost because who you are as an individual doesn’t stand out any longer. A lot of cooks are just cogs in the system so that the chef can get all the recognition. They do all the work but the chef gets everything. It’s not about the food anymore, right? It becomes more about the name and the personality. You don’t feel the heart or the passion.

What do they call you in the restaurant kitchen? Do they call you Mel? Ate Mel?

They call me Ate Mel. They call me Mother. Two of the people on my team actually grew up in the Philippines. Jonnah, who’s now the chef de cuisine here, came here when she was 19. JP came here when he was 10. It’s really beautiful because they speak Tagalog together so we still hear Tagalog in the kitchen. Bryant, who works with me in front of house, went to La Salle and came here when he was older. They bring a different kind of energy—the jokes, the sense of humor. The other cooks are Filipinx too, but Filipinx-American. It’s beautiful to watch it all come together because both the Filipinx and Filipinx-American experiences are so important and the fact that we can bridge that gap, which I think is so necessary to bridge, is also so beautiful here. They get to introduce their childhood memories too. I’m introduced to dishes that I never grew up with. Some of them are Ilokano, I’m Tagalog, JP’s from Pampanga; we’re able to showcase so much more and that’s very cool.

Everyone brings something to the table.

Yeah. And everyone is addressed with kindness and love and you can feel that in the food.

Thank you. I think it is. For me, how I approach food and how I want my team to approach food is: how are they connected to this dish? Does it speak to them? Are they excited about it? Because it’s not just about me putting a dish on the menu, it’s about them putting a dish on the menu. At the end of the day, all of us are just here to nourish people. We’ve had people come in here and cry because the food makes them remember a moment in their childhood and they’re so moved by it. All of us here are just trying to make something that can connect in a way that is far more important than the name attached to it.

I really hate the word “chef.” I really, truly do. There’s so much trauma for me that comes with the word chef. It makes me think of toxic masculinity and white male culture. I know it’s a form of respect, but I think in some ways it gets lost because who you are as an individual doesn’t stand out any longer. A lot of cooks are just cogs in the system so that the chef can get all the recognition. They do all the work but the chef gets everything. It’s not about the food anymore, right? It becomes more about the name and the personality. You don’t feel the heart or the passion.

What do they call you in the restaurant kitchen? Do they call you Mel? Ate Mel?

They call me Ate Mel. They call me Mother. Two of the people on my team actually grew up in the Philippines. Jonnah, who’s now the chef de cuisine here, came here when she was 19. JP came here when he was 10. It’s really beautiful because they speak Tagalog together so we still hear Tagalog in the kitchen. Bryant, who works with me in front of house, went to La Salle and came here when he was older. They bring a different kind of energy—the jokes, the sense of humor. The other cooks are Filipinx too, but Filipinx-American. It’s beautiful to watch it all come together because both the Filipinx and Filipinx-American experiences are so important and the fact that we can bridge that gap, which I think is so necessary to bridge, is also so beautiful here. They get to introduce their childhood memories too. I’m introduced to dishes that I never grew up with. Some of them are Ilokano, I’m Tagalog, JP’s from Pampanga; we’re able to showcase so much more and that’s very cool.

Everyone brings something to the table.

Yeah. And everyone is addressed with kindness and love and you can feel that in the food.

While she named her restaurant Musang after her dad, Melissa says that it’s her mom who’s been her biggest supporter. “My mom is the biggest cheerleader. I sometimes feel bad because my dad gets all the shine because it’s named after him, but it’s my mom who is the backbone of everything through the support and financial help she’s given me throughout my life.”

You’re very close to your parents and you named Musang after your dad. Can you tell us more about him?

My dad is a big personality. He’s gregarious, he’s funny, he’s loud, he’s like a big kid. He makes people feel warm and loved. He drove a black Mustang, but the “t” fell off, so he became Musang. And he’s a cat, he’s a wild cat. He’s super cool, he dresses really well, he’s like a ladies’ man. Everyone calls him Musang. Anywhere we’d go—the park, the movies, Chinatown—he knew everyone and everyone knew him. “Psst, Musang! Musang!” And I’d be like, is he the mayor? Why do people know him? He’s just so friendly.

My dad was always the one cooking Filipinx food in the house growing up, and he introduced that to me at a young age. He’s a big fisherman and he loves making his own daing. I was always with him, because my mom was working a lot too. When he was cooking, I’d want to help but I think he didn’t really want me there, so he’d give me the hardest jobs. I’d clean squid and it was so gross, but I did it. And I was always rolling lumpia for all the parties because my hands were little and I could roll fast.

I wanted to name the pop-up and the space after him, to honor him and what he taught me. On one trip to the Philippines, I went to visit coffee farms in Benguet with my friend Carmel who’s the founder of Kalsada Coffee. I was having a lot of back issues because of the line of work I’m in. They told me to see this healer who lived in the village. She saw my tattoos and asked in their dialect, why doesn’t she have a musang tattoo? When I heard it, it was a full-circle moment—in a place so far away, she’d mentioned my dad’s nickname. That memory is really profound.

It solidified my decision to name the space after my dad. It’s not about me; it’s about his story, the community that he created, and what Musang can mean for everyone else here. It’s kind of beautiful. There’s a cat in our logo, designed by a Filipinx artist. My dad’s first tattoo was the cat. And now he has lots of tattoos too. [Laughs.]

Did you get matching ones?

Yeah. And a lot of people on my team have it too.

Can you tell us more about what your childhood was like?

I was very fortunate. My mom has a lot of siblings that live here in Washington state, and her parents also live here, so I was really lucky to have a lot of cousins growing up. I’m an only child but I have a half-brother that I met later on in life. Family was always such a huge part of my growing up. I was very lucky to be surrounded by the food, the culture, the traditions, the hospitality.

Often, when Filipinos go abroad, there’s that idea of assimilation that needs to happen for success, and that came a lot from my mom. My mom was a nurse and she just really wanted to make sure that I was successful. My father is still very much Filipinx—and my mom is too—but my dad still has his accent. Growing up, he always reminded me of who I am: your blood is Filipinx, your skin color is Filipinx. Whereas my mom, when my dad would speak to me in Tagalog, she would tell him to speak to me in English. Sadly, I can’t speak Tagalog but I can understand it, which I think is the story of a lot of Filipinx-Americans here. But I was always surrounded by Filipinx food. It was always Filipinx food first, and then every other cuisine second. My baon would always be Filipinx food. Growing up, I had to reconcile with the fact that kids would make fun of my food, but I’m so grateful that my parents made sure I always had good lunches. A lot of my memories are attached to those meals.

How supportive have your parents been of your culinary career so far? Do they visit Musang often?

My mom is the biggest cheerleader. I sometimes feel bad because my dad gets all the shine because it’s named after him, but it’s my mom who is the backbone of everything through the support and financial help she’s given me throughout my life. When I had my pop-up in New York, she flew out for that. When I cooked at the James Beard House, she flew out for that. She’s always here for every single major life event. My dad too, but my mom has always really been the one supporting me and cheering me on. They’re both retired now, so it’s really cute when they come in because it’s like their home, too. The team loves them, my mom calls everyone her children.

Like, “Anak, halika dito!”

Yeah! They love it. They love her and my dad. My dad’s like the kid in the kitchen trying to disrupt everything. He’s like, “I’m Musang, I’m hungry!” [Laughs.] It really feels like a family here.

My dad is a big personality. He’s gregarious, he’s funny, he’s loud, he’s like a big kid. He makes people feel warm and loved. He drove a black Mustang, but the “t” fell off, so he became Musang. And he’s a cat, he’s a wild cat. He’s super cool, he dresses really well, he’s like a ladies’ man. Everyone calls him Musang. Anywhere we’d go—the park, the movies, Chinatown—he knew everyone and everyone knew him. “Psst, Musang! Musang!” And I’d be like, is he the mayor? Why do people know him? He’s just so friendly.

My dad was always the one cooking Filipinx food in the house growing up, and he introduced that to me at a young age. He’s a big fisherman and he loves making his own daing. I was always with him, because my mom was working a lot too. When he was cooking, I’d want to help but I think he didn’t really want me there, so he’d give me the hardest jobs. I’d clean squid and it was so gross, but I did it. And I was always rolling lumpia for all the parties because my hands were little and I could roll fast.

I wanted to name the pop-up and the space after him, to honor him and what he taught me. On one trip to the Philippines, I went to visit coffee farms in Benguet with my friend Carmel who’s the founder of Kalsada Coffee. I was having a lot of back issues because of the line of work I’m in. They told me to see this healer who lived in the village. She saw my tattoos and asked in their dialect, why doesn’t she have a musang tattoo? When I heard it, it was a full-circle moment—in a place so far away, she’d mentioned my dad’s nickname. That memory is really profound.

It solidified my decision to name the space after my dad. It’s not about me; it’s about his story, the community that he created, and what Musang can mean for everyone else here. It’s kind of beautiful. There’s a cat in our logo, designed by a Filipinx artist. My dad’s first tattoo was the cat. And now he has lots of tattoos too. [Laughs.]

Did you get matching ones?

Yeah. And a lot of people on my team have it too.

Can you tell us more about what your childhood was like?

I was very fortunate. My mom has a lot of siblings that live here in Washington state, and her parents also live here, so I was really lucky to have a lot of cousins growing up. I’m an only child but I have a half-brother that I met later on in life. Family was always such a huge part of my growing up. I was very lucky to be surrounded by the food, the culture, the traditions, the hospitality.

Often, when Filipinos go abroad, there’s that idea of assimilation that needs to happen for success, and that came a lot from my mom. My mom was a nurse and she just really wanted to make sure that I was successful. My father is still very much Filipinx—and my mom is too—but my dad still has his accent. Growing up, he always reminded me of who I am: your blood is Filipinx, your skin color is Filipinx. Whereas my mom, when my dad would speak to me in Tagalog, she would tell him to speak to me in English. Sadly, I can’t speak Tagalog but I can understand it, which I think is the story of a lot of Filipinx-Americans here. But I was always surrounded by Filipinx food. It was always Filipinx food first, and then every other cuisine second. My baon would always be Filipinx food. Growing up, I had to reconcile with the fact that kids would make fun of my food, but I’m so grateful that my parents made sure I always had good lunches. A lot of my memories are attached to those meals.

How supportive have your parents been of your culinary career so far? Do they visit Musang often?

My mom is the biggest cheerleader. I sometimes feel bad because my dad gets all the shine because it’s named after him, but it’s my mom who is the backbone of everything through the support and financial help she’s given me throughout my life. When I had my pop-up in New York, she flew out for that. When I cooked at the James Beard House, she flew out for that. She’s always here for every single major life event. My dad too, but my mom has always really been the one supporting me and cheering me on. They’re both retired now, so it’s really cute when they come in because it’s like their home, too. The team loves them, my mom calls everyone her children.

Like, “Anak, halika dito!”

Yeah! They love it. They love her and my dad. My dad’s like the kid in the kitchen trying to disrupt everything. He’s like, “I’m Musang, I’m hungry!” [Laughs.] It really feels like a family here.

From left to right: Melissa cooking at the studio with Amelia Franada; Melissa with the Kasama Space team: Kristina Capulong, Karen Leann Kirsch, and Andrew Imanaka.

There’s Musang, but you also have so much more on your plate. Musang Little Wildcats, your Filipinx cooking classes and kits for kids, is a really cute concept. How did this side project come about?

Stemming off of Musang not being a restaurant but a community space, there’s so much more that we can accomplish besides just educating people on food. Little Wildcats is a project with Marizel and Amelia who’s my pastry chef here. The idea was born when I took my cousin’s two kids to the children’s museum here in Seattle. My cousin is half-Filipinx, so her kids are a quarter-Filipinx. At the museum, there’s a little area where they have a Filipinx sari-sari store. It’s really, really cute. So the kids came and they were like, “Wow, this is so cool!” And I asked them, “Did you guys know that you’re Filipinx?” And they were like, what’s that? And I was like, what?! And I got so mad. [Laughs.] Their mom and I had this beautiful, heartfelt conversation. She was so sad because her dad, my mom’s brother, never passed it on to her. Her mom was Chilean and that side kind of took more prominence than the Filipino side.

So we thought it would be a really great idea to start introducing kids’ classes so that it was a way —not just for the kids but also the parents—to be able to connect to their heritage. I think a lot of Filipinx-Americans have that same experience where their parents didn’t teach them about their food, so they’re looking for that connection. We’ve been doing monthly meal kits that you can preorder and pick up, and they have all the ingredients you need to make a recipe. At the Kasama Space, we film an educational video that comes with the kit and you can cook along with. We’ve just been doing basics, a lot of foundational recipes, because we know that a lot of parents who are buying the kits want to learn those: afritada, sopas, lumpiang sariwa, pinakbet. The feedback has been really incredible and we hope to bring back in-person classes once it’s safer.

You mentioned Kasama Space, and you’ve also got Musangtino’s. Can you tell us more about these projects?

Jeffrey Santos is my partner for Musangtino’s—we grew up together and we reconnected when the pop-ups started. It was a way for us to figure out how we can do quick Filipinx food not as a full-service dining experience like Musang, but more a fast-casual concept at farmers’ markets or similar places. We started partnering with breweries here and we’re doing our own take on burgers and spaghetti, our own take on Jollibee, but like, better. [Laughs.] It’s a more fun atmosphere, people love them, we sell out. Maybe we’ll turn it into a brick-and-mortar in a couple years.

Kasama Space is a studio space dedicated to providing a way for BIPOC folks in our community to share their stories through food. We want to be able to create a more equal playing field because there’s not a lot of studio spaces that our community has access to. Kristina, my partner there, was one of the first people to help me with my pop-ups. She and I have worked together for years, she comes from a food and production background. We just want to be able to have a space where we can film videos; my BA videos and all of the Musang team videos are shot there. My team is starting to share recipes, so we also put that on our YouTube channel so they can start getting comfortable in that kind of role, because I wish someone gave me that opportunity. We film the Little Wildcats videos there too. We share the space with other chefs, so we can share their stories and they can share their stories too.

What excites you about Filipinx-American cooking and how do you think it has evolved?

It’s just really beautiful for these young cooks and leaders to feel like they can have a voice. I look at people like Lou Boquila in Philadelphia, Paolo Dungca in D.C., Francis Ang in San Francisco—there’s so much young talent that finally feels like they can. There’s a way that’s been paved. We’re gonna do it, and we’re gonna do it in all the ways. It’s important for us to look at all the entry and access points of how we can show what Filipino food is, from turo-turo and lutong bahay to modern Filipinx cooking and beautifully plated, exciting gastronomic experiences. It shows the talent and understanding of what we’ve learned from all these other people. What excites me the most is seeing how people are interpreting their own versions of what is Filipinx and paying respect to that and really trying to unlearn that “mine is better than yours” or “that’s not Filipinx” mentality. And they’re having the confidence to just be able to share that.

The Filipinx community in America is incredible. I talk to all of these chefs from all over the country. I check in with Carlo [Lamagna] from Portland, I check in with Chad [Valencia] from Lasa in L.A. I think it’s important for this next generation, for our future, for us to connect and not try and compete. We always say, it’s community, not competition. I truly believe that, because the only way our food can truly achieve the success that we hope for is if we all support each other.

That’s really what excites me. All these collaborations that are occurring with these young professionals from all over the country really wanting to expand the food. I love how in each city, it’s adapted to what is available. What Lasa cooks in L.A. is so different from what we cook here in Seattle by the produce that’s available by the season. Seeing the different takes is so inspiring. There’s so much that we’ve learned that we can apply to our own food and it’s really incredible to see.

I don’t know if you’ve heard of The Dusky Kitchen, but she’s a Filipinx-American baker and she had a pop-up in New York this weekend. She made kare-kare cookies.

Oh my god.

It was a peanut butter cookie with bagoong caramel on top and an annatto sugar coating. It blew my mind. I feel like you don’t usually see this kind of creativity in the Philippines, where food often conforms to a Western palate and uses ingredients that aren’t usually available there.

Yes! And the access to things like kamias or calamansi, things that we can’t get here, is taken for granted. My biggest takeaway from my time in the Philippines was that lack of progression in Filipinx cuisine. But a kare-kare cookie, that makes me so happy. It’s very interesting to see sometimes because there is this gap between Filipinxs and Filipinx-Americans, but at the end of the day we’re all trying to just share that story of what it means to be Filipinx and what our food tastes like.

Stemming off of Musang not being a restaurant but a community space, there’s so much more that we can accomplish besides just educating people on food. Little Wildcats is a project with Marizel and Amelia who’s my pastry chef here. The idea was born when I took my cousin’s two kids to the children’s museum here in Seattle. My cousin is half-Filipinx, so her kids are a quarter-Filipinx. At the museum, there’s a little area where they have a Filipinx sari-sari store. It’s really, really cute. So the kids came and they were like, “Wow, this is so cool!” And I asked them, “Did you guys know that you’re Filipinx?” And they were like, what’s that? And I was like, what?! And I got so mad. [Laughs.] Their mom and I had this beautiful, heartfelt conversation. She was so sad because her dad, my mom’s brother, never passed it on to her. Her mom was Chilean and that side kind of took more prominence than the Filipino side.

So we thought it would be a really great idea to start introducing kids’ classes so that it was a way —not just for the kids but also the parents—to be able to connect to their heritage. I think a lot of Filipinx-Americans have that same experience where their parents didn’t teach them about their food, so they’re looking for that connection. We’ve been doing monthly meal kits that you can preorder and pick up, and they have all the ingredients you need to make a recipe. At the Kasama Space, we film an educational video that comes with the kit and you can cook along with. We’ve just been doing basics, a lot of foundational recipes, because we know that a lot of parents who are buying the kits want to learn those: afritada, sopas, lumpiang sariwa, pinakbet. The feedback has been really incredible and we hope to bring back in-person classes once it’s safer.

You mentioned Kasama Space, and you’ve also got Musangtino’s. Can you tell us more about these projects?

Jeffrey Santos is my partner for Musangtino’s—we grew up together and we reconnected when the pop-ups started. It was a way for us to figure out how we can do quick Filipinx food not as a full-service dining experience like Musang, but more a fast-casual concept at farmers’ markets or similar places. We started partnering with breweries here and we’re doing our own take on burgers and spaghetti, our own take on Jollibee, but like, better. [Laughs.] It’s a more fun atmosphere, people love them, we sell out. Maybe we’ll turn it into a brick-and-mortar in a couple years.

Kasama Space is a studio space dedicated to providing a way for BIPOC folks in our community to share their stories through food. We want to be able to create a more equal playing field because there’s not a lot of studio spaces that our community has access to. Kristina, my partner there, was one of the first people to help me with my pop-ups. She and I have worked together for years, she comes from a food and production background. We just want to be able to have a space where we can film videos; my BA videos and all of the Musang team videos are shot there. My team is starting to share recipes, so we also put that on our YouTube channel so they can start getting comfortable in that kind of role, because I wish someone gave me that opportunity. We film the Little Wildcats videos there too. We share the space with other chefs, so we can share their stories and they can share their stories too.

What excites you about Filipinx-American cooking and how do you think it has evolved?

It’s just really beautiful for these young cooks and leaders to feel like they can have a voice. I look at people like Lou Boquila in Philadelphia, Paolo Dungca in D.C., Francis Ang in San Francisco—there’s so much young talent that finally feels like they can. There’s a way that’s been paved. We’re gonna do it, and we’re gonna do it in all the ways. It’s important for us to look at all the entry and access points of how we can show what Filipino food is, from turo-turo and lutong bahay to modern Filipinx cooking and beautifully plated, exciting gastronomic experiences. It shows the talent and understanding of what we’ve learned from all these other people. What excites me the most is seeing how people are interpreting their own versions of what is Filipinx and paying respect to that and really trying to unlearn that “mine is better than yours” or “that’s not Filipinx” mentality. And they’re having the confidence to just be able to share that.

The Filipinx community in America is incredible. I talk to all of these chefs from all over the country. I check in with Carlo [Lamagna] from Portland, I check in with Chad [Valencia] from Lasa in L.A. I think it’s important for this next generation, for our future, for us to connect and not try and compete. We always say, it’s community, not competition. I truly believe that, because the only way our food can truly achieve the success that we hope for is if we all support each other.

That’s really what excites me. All these collaborations that are occurring with these young professionals from all over the country really wanting to expand the food. I love how in each city, it’s adapted to what is available. What Lasa cooks in L.A. is so different from what we cook here in Seattle by the produce that’s available by the season. Seeing the different takes is so inspiring. There’s so much that we’ve learned that we can apply to our own food and it’s really incredible to see.

I don’t know if you’ve heard of The Dusky Kitchen, but she’s a Filipinx-American baker and she had a pop-up in New York this weekend. She made kare-kare cookies.

Oh my god.

It was a peanut butter cookie with bagoong caramel on top and an annatto sugar coating. It blew my mind. I feel like you don’t usually see this kind of creativity in the Philippines, where food often conforms to a Western palate and uses ingredients that aren’t usually available there.

Yes! And the access to things like kamias or calamansi, things that we can’t get here, is taken for granted. My biggest takeaway from my time in the Philippines was that lack of progression in Filipinx cuisine. But a kare-kare cookie, that makes me so happy. It’s very interesting to see sometimes because there is this gap between Filipinxs and Filipinx-Americans, but at the end of the day we’re all trying to just share that story of what it means to be Filipinx and what our food tastes like.

It’s very interesting to see sometimes because there is this gap between Filipinxs and Filipinx-Americans, but at the end of the day we’re all trying to just share that story of what it means to be Filipinx and what our food tastes like.

Similar to Filipinxs here, there’s a mindset in the Philippines that Filipinx food is not worth paying more for.

You know, it’s hard. My friend Ian [Carandang] owns Sebastian’s Ice Cream in the Philippines, and I love him because he’s the most extra beautiful, loudspoken person ever. Sometimes he’ll message me to tell me, that’s the most beautiful lumpiang sariwa I’ve ever seen, I’ve never seen it done here. And I’m like, you’re in the Philippines! I don’t understand! I think that when we talk about Filipinx food, we need to start talking about all the different entry points. We can exist on a turo-turo level, we can exist on a lutong bahay level, we should be able to introduce ourselves through these different things so that more people can see the value of who we are.

It doesn’t have to be one or the other.

It can, it should be all of it. I think people should experience all of it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Archipelago, but it’s here in Seattle and it’s run by Aaron [Verzosa] and Amber [Manuguid], and it’s an eight-seat, ten-course tasting menu that focuses on adapting Pacific Northwest flavors to Filipino cuisine. They charge $125 and there’s so many people who are like, “oh my God, it’s so expensive.” You’re not paying for the food, you’re paying for the experience. Our food can be valued that way. How do you think you can go to Le Bernardin and pay $150 and be like, “that was fabulous”? And this experience is way more intimate because they’re in front of you serving the food. There is a lot of work to be done but I think we are dedicated to making it happen.

In a way we’ve also been conditioned to think that we have to hold ourselves to a different kind of standard, at least when it comes to cooking.

I totally agree. It’s so evident with my mom now when she comes into the restaurant, and she’s like, I can’t believe there’s so many puti people here eating our food. Or when people tell me, you’ve elevated Filipinx food! I hate the word elevate in this context, because that means you never gave value to it in the first place. I think we’ve been conditioned as Filipinxs to think that our food isn’t good enough, or that it’s just lutong bahay, that’s it. It can’t be on this platform that can be celebrated. And we’ve dealt with a lot of that with the titos and the titas here who question our prices. “Why is it so expensive?” And our response is always, well, how can you pay $20 for sushi but you can’t pay $20 for your own food? You should be proud that we can price our food at that level because we think that we deserve it, we feel that we deserve it. That’s also been a part of that journey here at Musang—that extra education not just about what Filipino food tastes like, but also the value of our food and how we can be proud of it. It will take a lot of unlearning.

If you weren’t a chef, what would you be doing for a living?

I would probably be in policy or advocacy work. It’d be something I’d grow into, but it’s also something I’m very passionate about. A lot of it has to do with our Asian-American communities, especially here in Seattle. You see so much disparity, especially now with a lot of the hate that has always been occurring but is just recently getting the spotlight. How do we give people voices? How do we work towards equal pay? That’s something I’ve always been very vocal about. How can we make sure funds get allocated to businesses that deserve them, especially now? I think I’m finding a way to integrate that into my life. I’m slowly stepping away from the kitchen and the operational side of the restaurant, and trying to see how we can use the platform we’ve been able to create to advocate more for our people.

I have this vision of Musang as a movement, which is not really about Mel, right? It’s part of me making that happen. I think for me, what’s next is coming to terms and reconciling with the fact that I need to take the next step so that I can really truly represent and be a voice for the next generation. Just taking ownership. Not being afraid to hide behind myself anymore, living less in fear of the judgement of others, being loud and bold. There’s a lot more work to do, and I’m committed to making sure that work gets done. ︎

You know, it’s hard. My friend Ian [Carandang] owns Sebastian’s Ice Cream in the Philippines, and I love him because he’s the most extra beautiful, loudspoken person ever. Sometimes he’ll message me to tell me, that’s the most beautiful lumpiang sariwa I’ve ever seen, I’ve never seen it done here. And I’m like, you’re in the Philippines! I don’t understand! I think that when we talk about Filipinx food, we need to start talking about all the different entry points. We can exist on a turo-turo level, we can exist on a lutong bahay level, we should be able to introduce ourselves through these different things so that more people can see the value of who we are.

It doesn’t have to be one or the other.

It can, it should be all of it. I think people should experience all of it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Archipelago, but it’s here in Seattle and it’s run by Aaron [Verzosa] and Amber [Manuguid], and it’s an eight-seat, ten-course tasting menu that focuses on adapting Pacific Northwest flavors to Filipino cuisine. They charge $125 and there’s so many people who are like, “oh my God, it’s so expensive.” You’re not paying for the food, you’re paying for the experience. Our food can be valued that way. How do you think you can go to Le Bernardin and pay $150 and be like, “that was fabulous”? And this experience is way more intimate because they’re in front of you serving the food. There is a lot of work to be done but I think we are dedicated to making it happen.

In a way we’ve also been conditioned to think that we have to hold ourselves to a different kind of standard, at least when it comes to cooking.

I totally agree. It’s so evident with my mom now when she comes into the restaurant, and she’s like, I can’t believe there’s so many puti people here eating our food. Or when people tell me, you’ve elevated Filipinx food! I hate the word elevate in this context, because that means you never gave value to it in the first place. I think we’ve been conditioned as Filipinxs to think that our food isn’t good enough, or that it’s just lutong bahay, that’s it. It can’t be on this platform that can be celebrated. And we’ve dealt with a lot of that with the titos and the titas here who question our prices. “Why is it so expensive?” And our response is always, well, how can you pay $20 for sushi but you can’t pay $20 for your own food? You should be proud that we can price our food at that level because we think that we deserve it, we feel that we deserve it. That’s also been a part of that journey here at Musang—that extra education not just about what Filipino food tastes like, but also the value of our food and how we can be proud of it. It will take a lot of unlearning.

If you weren’t a chef, what would you be doing for a living?

I would probably be in policy or advocacy work. It’d be something I’d grow into, but it’s also something I’m very passionate about. A lot of it has to do with our Asian-American communities, especially here in Seattle. You see so much disparity, especially now with a lot of the hate that has always been occurring but is just recently getting the spotlight. How do we give people voices? How do we work towards equal pay? That’s something I’ve always been very vocal about. How can we make sure funds get allocated to businesses that deserve them, especially now? I think I’m finding a way to integrate that into my life. I’m slowly stepping away from the kitchen and the operational side of the restaurant, and trying to see how we can use the platform we’ve been able to create to advocate more for our people.

I have this vision of Musang as a movement, which is not really about Mel, right? It’s part of me making that happen. I think for me, what’s next is coming to terms and reconciling with the fact that I need to take the next step so that I can really truly represent and be a voice for the next generation. Just taking ownership. Not being afraid to hide behind myself anymore, living less in fear of the judgement of others, being loud and bold. There’s a lot more work to do, and I’m committed to making sure that work gets done. ︎

Liz Yap is a former magazine editor, writer, and brand strategist based in New York.