Out of

PJ Policarpio cuts through the noise

by Carina Santos

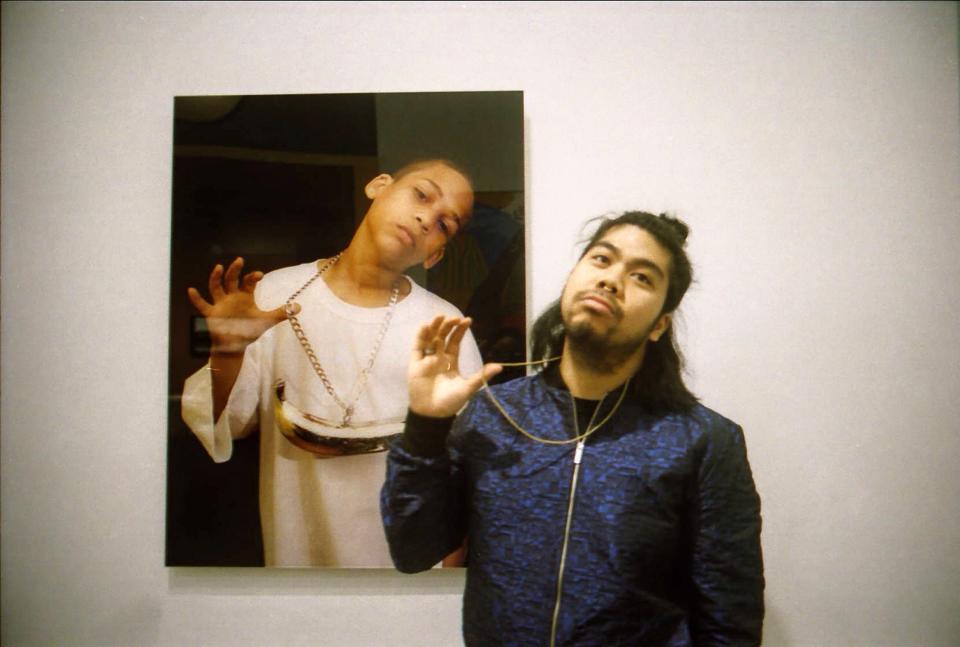

Photos courtesy of PJ Policarpio.

Museum educator and curator PJ Policarpio speaks about community, gathering, and the task of re-writing art history away from white Eurocentrism, one voice at a time.

PJ Gubatina Policarpio is a museum educator, curator, and community organizer, among other things. He moved to the U.S. in his early teens and has worked in institutions such as the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Contemporary Jewish Museum. Currently, he works on youth-based initiatives at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco as the manager of youth development. He has lectured extensively and through his projects, aims towards multicultural dialogues that put intersectional minority communities at the forefront of the conversations.

With Emmy Catedral, PJ also founded the Pilipinx American Library (PAL), “a bi-coastal, mobile, non-circulating library that celebrates print histories and collects narratives by writers, poets, artists, and scholars across the diaspora.” Through PAL, they invoked Al Robles’ sentiment: “We dreamt of a place to gather.” The current global situation, where many have been discouraged to meet and gather has seemingly posed a threat to this idea—at least in a physical sense—and has proven to make this goal a little harder to reach.

But, speaking with PJ over yet another Zoom meeting has opened my eyes to the possibility of connection despite the absence of physical presence, and has encouraged a sense of community that is built across oceans, something that is created through choosing deliberately and meaningfully the voices you want to cut through the noise.

︎

Out of Print: Hi, PJ. How was your weekend?

PJ Policarpio: Good, good. I teach in the morning, so I was doing that, but now, I’m taking a break to eat, make some coffee…

Thanks for taking the time!

Yeah, I’m so glad we could connect. This was probably the best and fastest way, because I was in between so many projects and so many things. It’s probably better just to chat. Plus, it will be more friendly, and less kind of formal, I think.

Yeah, I was reading through what I sent you, and thought “Oh, this is probably too much to ask over email.”

I know! And we’ve followed each other for so long, so you probably know so much already. [Laughs]

Yes! I mean, I’ve always wanted to speak to you about the work that you do, because it’s always been interesting to me, so I’m really happy we can get to do that right now. So, what have you been up to? It seems like every time I talk to you, you’re always doing something else, or that you’ve wrapped another project.

I know, I know. So, right now, I’m working at the Fine Arts Museum here in San Francisco. So, I work around our youth initiative for teens, all the way to 24-year-olds. We work around internships and young professionals around that. So, that’s kind of like my full-time job. Right now, we’re working from home because San Francisco is still under Covid restrictions.

And then a few other things have come up, which includes curating a group show of grad fellows at the Headlands [Centre for the Arts], which offers a year-long fellowship for recently graduated MFA students from the top six art schools in the Bay Area. So I’m really excited because I’m doing virtual studio visits with them. I’ve been doing that for the last three weeks, so this weekend is my last one with them to do a kind of initial visit or conversation around their artwork. And then I’m doing another one in March.

I have some time in between to kind of organize everything, and then the exhibition opens in May. It’s still an in-person exhibition, which is really exciting. But right now, I’m just talking to them about what it has been like to make art under such an extraordinary time and moment, you know. A year that has been unlike any other year so far. As part of their award, they each get a studio space at the Headlands, and they have access to work and also to this whole community. The community part of it kind of it disappears, because we’re discouraged from gathering, so I’m interested in how that changes their work, their processes, the materials that they use.

From the conversations I’ve been having, it’s really been feeling isolating, so people have been turning towards intimate gestures and an economy in materials, thinking less and less about materials and less and less about making big and monumental things. But really, making things that you can carry, things that are close to the body. Those are the initial threads that I’ve been getting from the artists.

PJ Policarpio: Good, good. I teach in the morning, so I was doing that, but now, I’m taking a break to eat, make some coffee…

Thanks for taking the time!

Yeah, I’m so glad we could connect. This was probably the best and fastest way, because I was in between so many projects and so many things. It’s probably better just to chat. Plus, it will be more friendly, and less kind of formal, I think.

Yeah, I was reading through what I sent you, and thought “Oh, this is probably too much to ask over email.”

I know! And we’ve followed each other for so long, so you probably know so much already. [Laughs]

Yes! I mean, I’ve always wanted to speak to you about the work that you do, because it’s always been interesting to me, so I’m really happy we can get to do that right now. So, what have you been up to? It seems like every time I talk to you, you’re always doing something else, or that you’ve wrapped another project.

I know, I know. So, right now, I’m working at the Fine Arts Museum here in San Francisco. So, I work around our youth initiative for teens, all the way to 24-year-olds. We work around internships and young professionals around that. So, that’s kind of like my full-time job. Right now, we’re working from home because San Francisco is still under Covid restrictions.

And then a few other things have come up, which includes curating a group show of grad fellows at the Headlands [Centre for the Arts], which offers a year-long fellowship for recently graduated MFA students from the top six art schools in the Bay Area. So I’m really excited because I’m doing virtual studio visits with them. I’ve been doing that for the last three weeks, so this weekend is my last one with them to do a kind of initial visit or conversation around their artwork. And then I’m doing another one in March.

I have some time in between to kind of organize everything, and then the exhibition opens in May. It’s still an in-person exhibition, which is really exciting. But right now, I’m just talking to them about what it has been like to make art under such an extraordinary time and moment, you know. A year that has been unlike any other year so far. As part of their award, they each get a studio space at the Headlands, and they have access to work and also to this whole community. The community part of it kind of it disappears, because we’re discouraged from gathering, so I’m interested in how that changes their work, their processes, the materials that they use.

From the conversations I’ve been having, it’s really been feeling isolating, so people have been turning towards intimate gestures and an economy in materials, thinking less and less about materials and less and less about making big and monumental things. But really, making things that you can carry, things that are close to the body. Those are the initial threads that I’ve been getting from the artists.

Carlos [Villa] was really at the forefront of multiculturalism in the ‘70s, and the ‘80s, and the ‘90s. His primary questions were really around “where are we?” as a people. What are we celebrating?

Can you tell me a bit more about the Carlos Villa retrospective you’re working on as well?

Carlos is such a towering figure, not just in Filipino-American art history, but in American art history in general, specifically in the Bay Area, where he was really part of the community. He was an educator for a long time, an art teacher, a mentor, a leading organizer, an activist. He was making work and had an active studio practice, but he also organized events, gatherings and symposiums, where people could think about multiculturalism.

One of his premiere contributions was Other Sources, which was this pioneering 1970s exhibition that really took social practice even before there was social practice, taking this idea that artists could work with communities, this idea that gathering and eating is, on its own, a creative practice. That’s something that is so relevant. So, he is somebody that I kind of really look up to, and in a way, saw a map, even though I only really knew of him, you know, really closely in the last maybe five years.

So, there is going to be a major retrospective of all of the aspects of his work at the Asian Art Museum, in collaboration with San Francisco Art Institute, which was his domain where he taught for the longest time. That will also travel, but because of Covid, that will get pushed back a little.

For this project, I’m working with a great team of other curators, other thinkers, some of whom are Carlos’ mentees and students, to come up with a public program, so we’re kind of really thinking about how we can continue the conversations that Carlos Villa started around multiculturalism, what we call “diversity”, and equity issues. Carlos was really at the forefront of this in the ‘70s, and the ‘80s, and the ‘90s. His primary questions were really around “where are we?” as a people. What are we celebrating? You know, the issues that artists of colors face. And he was asking this in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s.

So, with the programming, I wanted to revisit the same issues, but also think about how we can look forward. What can we work on together? There is a strong sense of solidarity. Carlos’ work—his curatorial work, if we can say that—he always included Latino artists, other Asian American artists. You know, he worked with Ruth Asawa, who is having such a great moment, which is so long overdue. And so many other artists, Black artists in the ‘70s… He had such a multiperspective kind of approach, and he always advocated for diversity, greater appreciation for artists of color, and art that stems from specific experiences outside of the margins, against Eurocentric, white art history.

The art history that he was interested in and that he promoted was that of a multicultural art history that included experiences from multiple people, and also America’s experiences, and so I just saw a deep parallel in that practice, with my own practice, so I was really excited to be a part of it. Right now we are kind of just organizing what kinds of programs do we have, what kind of conversations, and voices do we want to hear. I’ve tried not to overextend myself. I’ve learned in the last few years to only accept work that I’m already really excited about.

Yeah, you seem really excited about this. [Laughs] And I actually really wish I could see it. I can’t believe we don’t really get to learn about people like him. Like you, you’ve been involved in the arts for so long, and you’ve only really managed to do a deep dive, like you said, around five years ago. That’s insane.

Yeah! And I grew up in the Bay Area. It’s not in the art history courses or books.

Carlos is such a towering figure, not just in Filipino-American art history, but in American art history in general, specifically in the Bay Area, where he was really part of the community. He was an educator for a long time, an art teacher, a mentor, a leading organizer, an activist. He was making work and had an active studio practice, but he also organized events, gatherings and symposiums, where people could think about multiculturalism.

One of his premiere contributions was Other Sources, which was this pioneering 1970s exhibition that really took social practice even before there was social practice, taking this idea that artists could work with communities, this idea that gathering and eating is, on its own, a creative practice. That’s something that is so relevant. So, he is somebody that I kind of really look up to, and in a way, saw a map, even though I only really knew of him, you know, really closely in the last maybe five years.

So, there is going to be a major retrospective of all of the aspects of his work at the Asian Art Museum, in collaboration with San Francisco Art Institute, which was his domain where he taught for the longest time. That will also travel, but because of Covid, that will get pushed back a little.

For this project, I’m working with a great team of other curators, other thinkers, some of whom are Carlos’ mentees and students, to come up with a public program, so we’re kind of really thinking about how we can continue the conversations that Carlos Villa started around multiculturalism, what we call “diversity”, and equity issues. Carlos was really at the forefront of this in the ‘70s, and the ‘80s, and the ‘90s. His primary questions were really around “where are we?” as a people. What are we celebrating? You know, the issues that artists of colors face. And he was asking this in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s.

So, with the programming, I wanted to revisit the same issues, but also think about how we can look forward. What can we work on together? There is a strong sense of solidarity. Carlos’ work—his curatorial work, if we can say that—he always included Latino artists, other Asian American artists. You know, he worked with Ruth Asawa, who is having such a great moment, which is so long overdue. And so many other artists, Black artists in the ‘70s… He had such a multiperspective kind of approach, and he always advocated for diversity, greater appreciation for artists of color, and art that stems from specific experiences outside of the margins, against Eurocentric, white art history.

The art history that he was interested in and that he promoted was that of a multicultural art history that included experiences from multiple people, and also America’s experiences, and so I just saw a deep parallel in that practice, with my own practice, so I was really excited to be a part of it. Right now we are kind of just organizing what kinds of programs do we have, what kind of conversations, and voices do we want to hear. I’ve tried not to overextend myself. I’ve learned in the last few years to only accept work that I’m already really excited about.

Yeah, you seem really excited about this. [Laughs] And I actually really wish I could see it. I can’t believe we don’t really get to learn about people like him. Like you, you’ve been involved in the arts for so long, and you’ve only really managed to do a deep dive, like you said, around five years ago. That’s insane.

Yeah! And I grew up in the Bay Area. It’s not in the art history courses or books.

Gina Apostol doing a reading at the Pilipinx American Library.

“...there’s still this inability to mourn together and be together. I think all of those things taught me to center people in my curatorial practice, in my teaching practice, in all my ways of working. Just to be human.”

How has the situation affected how you’ve been working? Just from hearing what you’ve been involved in. A lot of it seems collaborative, and engages communities, so I’m wondering how that’s gone for you.

A lot of my work is deeply collaborative, and I’d like to, if I can, work with people I really admire and respect. And the pandemic has for the most part allowed folks to meet without having to travel, so a lot of that has been cut off, but it’s also really helped me to think about narrowing down that I’m personally excited about and inspired by, and think that I’d have a great voice for. And if I don’t say yes to those three things, then I’d rather focus on rest and my wellbeing.

But, also in terms of an approach, I think that it’s really hard to think about so much professionally… you know, “What do I want to have accomplished this year?” “What do I want to curate this year?” “What do I want to work on?” These things, I didn’t actively seek out, they kind of invited me to be a part of, but you know, I’m not kind of in that zone of being productive all the time.

Last year, a few moments right after the outbreak, I was asked to kind of write and reflect how this has influenced my curatorial practice. And I said, I’m not really thinking about all of these things. I was worried about the impact that the pandemic had, disproportionately, on Black and brown communities, marginalized communities… Anti-Asian racism was really happening, and at the same time, Filipinx and healthcare workers were at the frontlines of this work, and they were more susceptible to this virus. Just looking at where the outbreaks were happening, one of them was a neighborhood that I used to live in in New York, Woodside. It’s a working class, migrant, immigrant neighborhood.

There’s a hospital there—there’s a Jollibee there, if that helps you visualize. It’s the epicenter of Filipino-American life. That’s where you go to get your Filipino grocery, to get your boxes shipped. There’s a Goldilocks, a Red Ribbon, and that was badly hit. That’s where people were dying in numbers, and so, I was like… I can’t think about art! I can’t think about curating. I can’t think about which artist is really interesting right now. I really couldn’t think in that sphere. And I really was in a more personal way, attached to that neighborhood and what it taught me, and kind of that ethos of that neighborhood.

Seeing this place that you love kind of be destroyed by this virus and nobody seeming to care. On top of that, there’s anti-Asian racism, so that was a priority. I took my time. I can’t force myself to be like, “Oh, there has to be a show about coronavirus!” Or you know, who’s making interesting art about the virus.

So it put things in perspective, and showed me what’s more important. So that’s why those projects—especially the Carlos Villa project… it felt really important to share his voice. Because he was so community-driven. He was so multicultural.

![]()

I do find it interesting that we were talking about the absence or the overhaul of what “community” means and how we can’t actually meet each other right now, and how you’ve gravitated someone who was actively seeking it. There is a tension between that and what we can’t kind of do now, that we can’t really meet.

Yeah, I think in some ways, essentially, we can meet anybody. Like, you’re in London, I’m in San Francisco. We don’t really need to be in the same space, the same country, to connect, and that’s a tremendous opportunity, but also at the same time, you have something to protect. Now that you can meet everybody, do you want to meet everybody? [Laughs]

Yes, the possibility is there, but at the same time, how do you want to take advantage? But, it’s exhausting. I work 30 hours, 40 hours a week, and that’s screen-based. Any more than all of these projects can add more screen time, and that is kind of a part of it.

There’s also the human part. We can’t just look at this in art world terms. I’m very aware; I’ve worked in museums for a very long time, both in New York and San Francisco. I have a lot of artist friends, curator friends, but we can’t always just look at it through that lens. We really have to look at it through a human lens, knowing that people are suffering. People are dying. In a lot of ways, people haven’t mourned. I lost my grandmother last year—my dad’s mom. Not through the virus, but there’s still this inability to mourn together and be together. I think all of those things taught me to center people in my curatorial practice, in my teaching practice, in all my ways of working. Just to be human.

A lot of my work is deeply collaborative, and I’d like to, if I can, work with people I really admire and respect. And the pandemic has for the most part allowed folks to meet without having to travel, so a lot of that has been cut off, but it’s also really helped me to think about narrowing down that I’m personally excited about and inspired by, and think that I’d have a great voice for. And if I don’t say yes to those three things, then I’d rather focus on rest and my wellbeing.

But, also in terms of an approach, I think that it’s really hard to think about so much professionally… you know, “What do I want to have accomplished this year?” “What do I want to curate this year?” “What do I want to work on?” These things, I didn’t actively seek out, they kind of invited me to be a part of, but you know, I’m not kind of in that zone of being productive all the time.

Last year, a few moments right after the outbreak, I was asked to kind of write and reflect how this has influenced my curatorial practice. And I said, I’m not really thinking about all of these things. I was worried about the impact that the pandemic had, disproportionately, on Black and brown communities, marginalized communities… Anti-Asian racism was really happening, and at the same time, Filipinx and healthcare workers were at the frontlines of this work, and they were more susceptible to this virus. Just looking at where the outbreaks were happening, one of them was a neighborhood that I used to live in in New York, Woodside. It’s a working class, migrant, immigrant neighborhood.

There’s a hospital there—there’s a Jollibee there, if that helps you visualize. It’s the epicenter of Filipino-American life. That’s where you go to get your Filipino grocery, to get your boxes shipped. There’s a Goldilocks, a Red Ribbon, and that was badly hit. That’s where people were dying in numbers, and so, I was like… I can’t think about art! I can’t think about curating. I can’t think about which artist is really interesting right now. I really couldn’t think in that sphere. And I really was in a more personal way, attached to that neighborhood and what it taught me, and kind of that ethos of that neighborhood.

Seeing this place that you love kind of be destroyed by this virus and nobody seeming to care. On top of that, there’s anti-Asian racism, so that was a priority. I took my time. I can’t force myself to be like, “Oh, there has to be a show about coronavirus!” Or you know, who’s making interesting art about the virus.

So it put things in perspective, and showed me what’s more important. So that’s why those projects—especially the Carlos Villa project… it felt really important to share his voice. Because he was so community-driven. He was so multicultural.

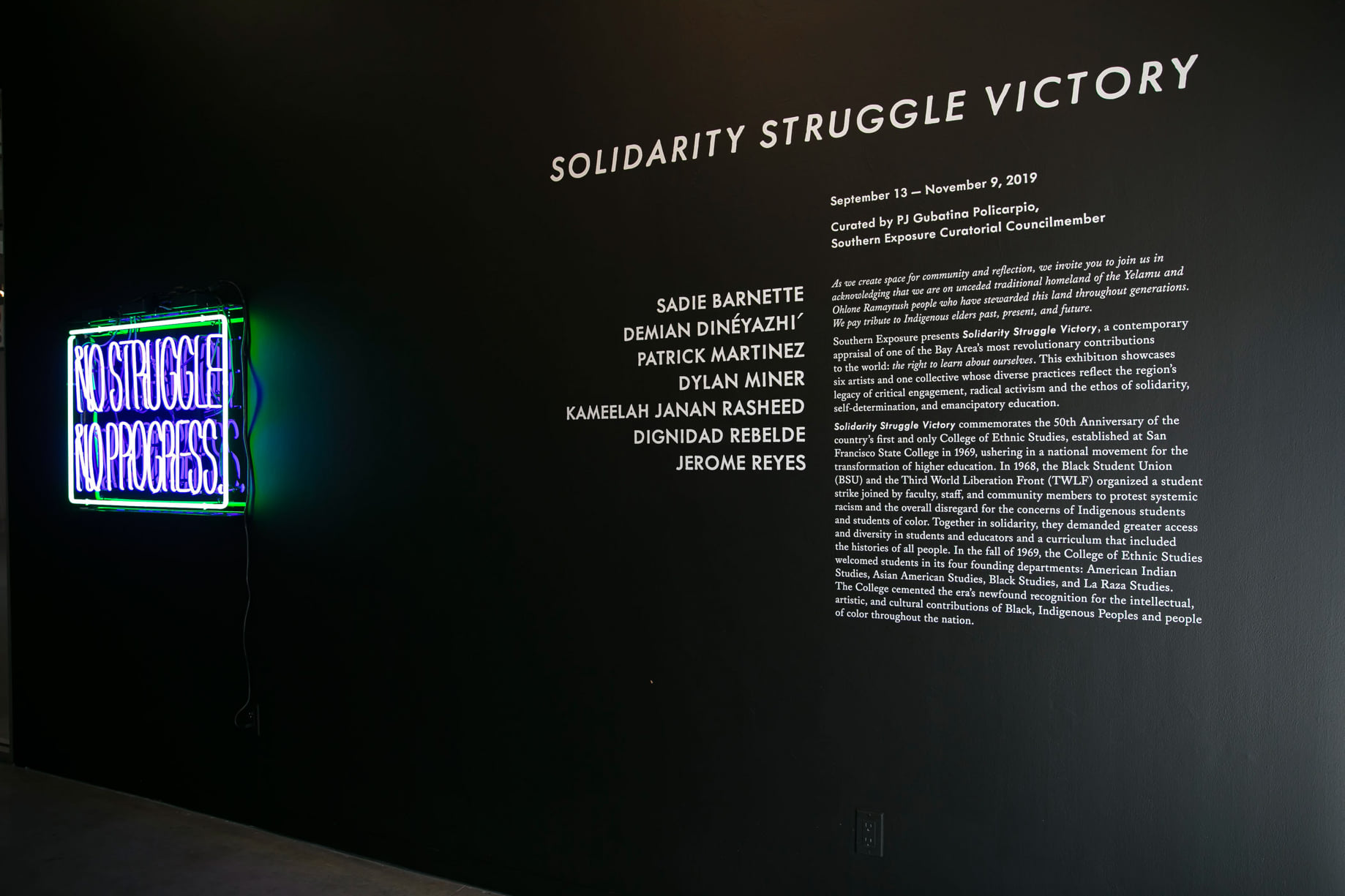

Solidarity, Struggle, Victory, one of the shows PJ curated for Southern Exposure in 2019.

I do find it interesting that we were talking about the absence or the overhaul of what “community” means and how we can’t actually meet each other right now, and how you’ve gravitated someone who was actively seeking it. There is a tension between that and what we can’t kind of do now, that we can’t really meet.

Yeah, I think in some ways, essentially, we can meet anybody. Like, you’re in London, I’m in San Francisco. We don’t really need to be in the same space, the same country, to connect, and that’s a tremendous opportunity, but also at the same time, you have something to protect. Now that you can meet everybody, do you want to meet everybody? [Laughs]

Yes, the possibility is there, but at the same time, how do you want to take advantage? But, it’s exhausting. I work 30 hours, 40 hours a week, and that’s screen-based. Any more than all of these projects can add more screen time, and that is kind of a part of it.

There’s also the human part. We can’t just look at this in art world terms. I’m very aware; I’ve worked in museums for a very long time, both in New York and San Francisco. I have a lot of artist friends, curator friends, but we can’t always just look at it through that lens. We really have to look at it through a human lens, knowing that people are suffering. People are dying. In a lot of ways, people haven’t mourned. I lost my grandmother last year—my dad’s mom. Not through the virus, but there’s still this inability to mourn together and be together. I think all of those things taught me to center people in my curatorial practice, in my teaching practice, in all my ways of working. Just to be human.

Exhibition view of Solidarity, Struggle, Victory at Southern Exposure.

Exhibition view of Solidarity, Struggle, Victory at Southern Exposure.You sent me links to the Southern Exposure project and the Notes for Tomorrow project. Were these made in response to the pandemic? I particularly liked the inclusion of poetry.

I’m part of Southern Exposure’s curatorial committee, so when the city said that, because of the restrictions, there’s no public gatherings, we came up with what we thought would be an appropriate response from the gallery, which is an on-site gallery. I thought maybe one thing we can do is something that’s more literary.

I also knew that my poet friends were struggling. A lot of them lost a lot of their source of income, so I thought one thing we could do was commission poems. So I invited five folks to create and share poetry that is either in response to or is relevant to the moment, which was last year around September to November.

We shared them in this virtual online exhibition (First Made Into Language), and then it became a real publication. We made it as a riso kind of zine. The poetry is in here, then the images are also here. So the whole exhibition is online, and is this form of like a book publication. This is something I love working in, too. This is essentially an exhibition in a form of a publication.

The ICI project was an invitation. They invited over 30 curators from all over the world in their network, to select something, and I suggested Demian [DinéYazhi’]’s work. I did very minimal work for that. I selected one work and worked with one artist. They have a beautiful design, it’s really great.

I’m part of Southern Exposure’s curatorial committee, so when the city said that, because of the restrictions, there’s no public gatherings, we came up with what we thought would be an appropriate response from the gallery, which is an on-site gallery. I thought maybe one thing we can do is something that’s more literary.

I also knew that my poet friends were struggling. A lot of them lost a lot of their source of income, so I thought one thing we could do was commission poems. So I invited five folks to create and share poetry that is either in response to or is relevant to the moment, which was last year around September to November.

We shared them in this virtual online exhibition (First Made Into Language), and then it became a real publication. We made it as a riso kind of zine. The poetry is in here, then the images are also here. So the whole exhibition is online, and is this form of like a book publication. This is something I love working in, too. This is essentially an exhibition in a form of a publication.

The ICI project was an invitation. They invited over 30 curators from all over the world in their network, to select something, and I suggested Demian [DinéYazhi’]’s work. I did very minimal work for that. I selected one work and worked with one artist. They have a beautiful design, it’s really great.

The Pilipinx American Library.

The Pilipinx American Library.“Essentially PAL was really made to engage in a gathering setting, in a collaborative, collective setting, and now that that has been discouraged, so we’re just thinking about how that project can exist other than bringing people together in one space.”

There’s so many things that are happening in the U.S. other than the pandemic.

Yeah, over the summer… George Floyd’s death, that brought on a lot of the racial reckoning in the country, and also all over the world. The diasporic Black experiences across the globe, especially with colonialism in Europe and slavery here, and so all of these unanswered questions came up. And so, it was a year that really brought all of this into the foreground.

It’s about time, but it’s also a lot all at once.

It’s a long overdue conversation. But you know, it’s interesting that it’s all at once. It’s the virus, the racism, the economic inequity happening, joblessness, and then also ecological things happening. So, they all decided to come out.

I wonder if it’s because we’re all plugged in, so we’re all aware of what’s happening.

We’re all at home.

Yeah, it’s kind of looking to connect, and like you said, collectively mourn something, or also be enraged by something.

Exactly. How is it over there? How are these conversations happening in London?

I’m really surprised. It’s very diverse, but the U.K. is also still very conservative, but in a “polite” way, kind of.

Brexit was also happening! And conservatism, and anti-immigration.

Yeah, so many things were happening.

It’s so interesting to see diasporic folks, and you’re like, “Oh, we have different issues in the Philippines, but here and in the U.K., there are also different issues.

I guess you’re also updated with the stuff that’s happening back home. Do you still have family there?

My dad’s side, my uncles and aunts and their families. But on my mom’s side, almost all of my cousins are here.

It just feels like a lot to think about all at once and yeaah, I can understand why a lot of people aren’t in the mindset of being productive and doing work. I was going to ask about PAL (Pilpinx American Library). Is that still going on?

Yes! It’s just been on a long pause, just because it’s been, well, you know. Everything is kind of closing down, but also my collaborator, Emmy [Catedral], is in New York. We try to collaborate, but also, we figure there’s many other sources. I’m hopeful that it can kind of emerge again in some way or form. We’re looking to publish a series of texts that we commissioned, so it may come in a book form. Essentially PAL was really made to engage in a gathering setting, in a collaborative, collective setting, and now that that has been discouraged, so we’re just thinking about how that project can exist other than bringing people together in one space. I’m hoping to publish a series of commissioned texts from two years ago, to finally just kind of put it in archive form.

I think archives ebb and flow as needed, so I’m looking forward to seeing what the next version will be or how it will continue, and also, curious.︎

Yeah, over the summer… George Floyd’s death, that brought on a lot of the racial reckoning in the country, and also all over the world. The diasporic Black experiences across the globe, especially with colonialism in Europe and slavery here, and so all of these unanswered questions came up. And so, it was a year that really brought all of this into the foreground.

It’s about time, but it’s also a lot all at once.

It’s a long overdue conversation. But you know, it’s interesting that it’s all at once. It’s the virus, the racism, the economic inequity happening, joblessness, and then also ecological things happening. So, they all decided to come out.

I wonder if it’s because we’re all plugged in, so we’re all aware of what’s happening.

We’re all at home.

Yeah, it’s kind of looking to connect, and like you said, collectively mourn something, or also be enraged by something.

Exactly. How is it over there? How are these conversations happening in London?

I’m really surprised. It’s very diverse, but the U.K. is also still very conservative, but in a “polite” way, kind of.

Brexit was also happening! And conservatism, and anti-immigration.

Yeah, so many things were happening.

It’s so interesting to see diasporic folks, and you’re like, “Oh, we have different issues in the Philippines, but here and in the U.K., there are also different issues.

I guess you’re also updated with the stuff that’s happening back home. Do you still have family there?

My dad’s side, my uncles and aunts and their families. But on my mom’s side, almost all of my cousins are here.

It just feels like a lot to think about all at once and yeaah, I can understand why a lot of people aren’t in the mindset of being productive and doing work. I was going to ask about PAL (Pilpinx American Library). Is that still going on?

Yes! It’s just been on a long pause, just because it’s been, well, you know. Everything is kind of closing down, but also my collaborator, Emmy [Catedral], is in New York. We try to collaborate, but also, we figure there’s many other sources. I’m hopeful that it can kind of emerge again in some way or form. We’re looking to publish a series of texts that we commissioned, so it may come in a book form. Essentially PAL was really made to engage in a gathering setting, in a collaborative, collective setting, and now that that has been discouraged, so we’re just thinking about how that project can exist other than bringing people together in one space. I’m hoping to publish a series of commissioned texts from two years ago, to finally just kind of put it in archive form.

I think archives ebb and flow as needed, so I’m looking forward to seeing what the next version will be or how it will continue, and also, curious.︎

Carina Santos is an artist and writer.