Out of Print

The women behind Sari-Sari Studio offer a frank discussion on the Filipino-American diaspora and deepens this writer’s understanding of it in the process.

Here are some things that have already been written about Sari-Sari: for one, Gabriella Mozo and Marielle Sales are two first-generation Filipino American women who work in the creative industry. Marielle is a photographer and does events and digital strategy for a PR firm in New York City. Gabriella has worked in fashion design and currently works as a clothing designer. Secondly, Gabriella and Marielle didn't become friends until they moved to Brooklyn in their adulthood, despite growing up in the same city in New Jersey. Gabriella put out an ad for a roommate. Marielle replied to it, and they've been friends since

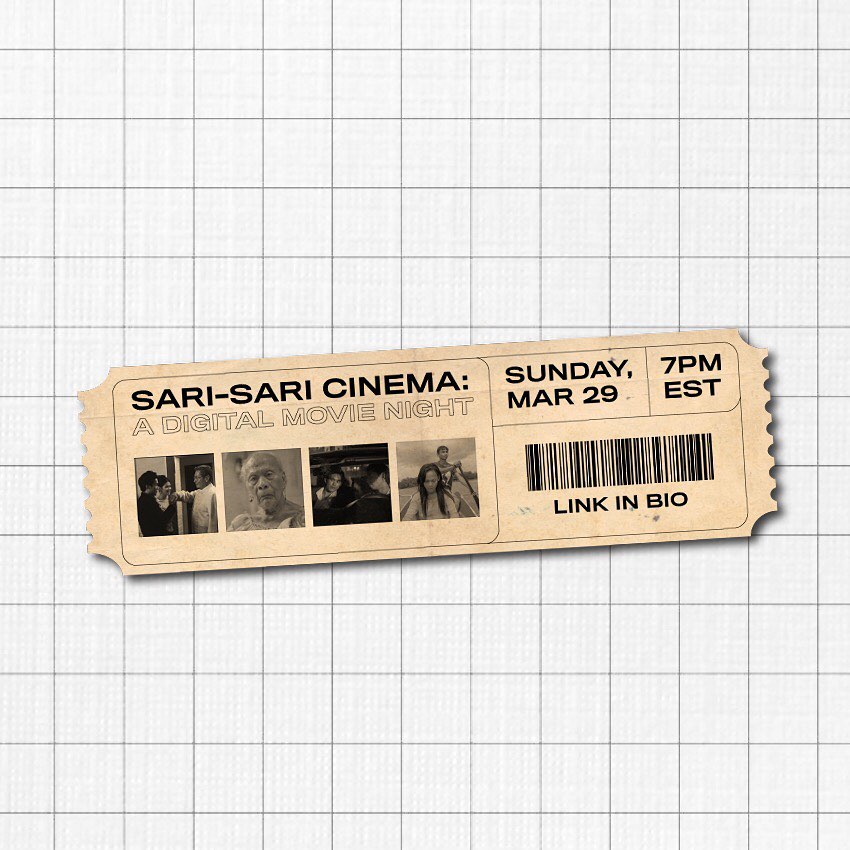

An opportunity came in 2018 where the girls could join a pop-up for an NYC community event. “We just wanted to sell stuff we had in a closet sale,” Marielle says. “We just had this group chat with a few friends who were Filipinx, and we wanted to come together to sell secondhand clothing and some other stuff. Someone in the group said, ‘Oh, we should call it Sari-Sari,’” referring to the near-ubiquitous Filipino mixed business corner store. In the context they were in, Gabriella thought the name might be confused with the more famous Indian sari. They decided to add “General Store” to it—something easily identifiable and, as Gabriella explains, something super-American. Still, this seemingly simple addition felt like a cultural handshake between Filipino and American—representative of the ideals and aesthetic for which Sari-Sari would come to be known.

After the initial pop-up's success, Gabriella and Marielle decided to run with it, to see if Sari-Sari General Store could present a modern iteration of Filipino tradition and Filipinx culture through commerce and community events. “My background is in design, and Marielle has lots of experience putting up brand activations, so we've been pretty successful in setting up these experiences for the community,” says Gabriella. Their second pop-up, Kapwa at the Canal Street Market, was more visibly upfront about their Filipino heritage as an aesthetic: from a booth that looked like a small, wooden sari-sari storefront with Filipino snacks hung up on the façade, to a mini Filipino flag held up by an empty can of Spam, to a Filipinx lineup of creatives DJ-ing and sharing art at the event. It was a celebration of their heritage and perhaps an introduction to a community of like-minded BIPOC people, especially Filipino Americans who had not yet been in touch with their roots.

Sari-Sari Studio’s Mal Tayag, Gabriella Mozo, and Marielle Sales.

Sari-Sari Studio’s Mal Tayag, Gabriella Mozo, and Marielle Sales.I had been following Gabriella, Marielle, and Sari-Sari on social media for a while, first discovering them through a Hypebae article they themselves produced, which included fellow Filipino American creatives as well as brands from the Philippines in early 2019. I had served as Brand Manager for one of the featured brands, and a couple of others were made by friends. The stuff in the feature was relatively new, so I wanted to know more about the team and how they came to include my brand in the lineup.

The shoot's treatment felt very different from any other feature I'd seen of Filipino American life. Everything was bright but with no red, yellow, and blue, typical of “Filipino pride” imagery. It was joyful, but with no images of people sitting by aluminum tubs of food. It was Filipino-esque, infused with the muted slow fashion aesthetic of the West—denim butterfly sleeves, glazed stoneware palayoks in place of terracotta, and an inabel weave in binakol print casually hung on top of white linen as the background sampayan. It was purposefully restrained, perhaps to present the Filipino identity outside the confines of moms with funny accents, plastic-covered couches, and uncles named Jun.

Filipinos who are native to the Philippines often tend to police the authentic “Filipinoness” of any Filipino American activity. I found myself falling into the same habit as I watched Sari-Sari do their thing. “It's so New York,” I told myself, after reading how Gabriella likened the Filipino Sari-Sari Store to a bodega. “That's not really what it's like.” As I drew on the imagery of tiny caged windows, I continued to think of shampoo sachets hung on window grills and televisions playing loud noontime shows. “Kulang,” I lamented. In my brief moment of cultural self-righteousness, I realized that I felt like Filipino culture was being taken out of context. In the case of the diaspora, that is really what is happening, and it is the context in which Gabriella's or Marielle's Filipinoness occurs. Though it vaguely looks like mine, the Filipino identity for Filipino Americans is not for me to define, as a Filipino living in the Philippines.

The shoot's treatment felt very different from any other feature I'd seen of Filipino American life. Everything was bright but with no red, yellow, and blue, typical of “Filipino pride” imagery. It was joyful, but with no images of people sitting by aluminum tubs of food. It was Filipino-esque, infused with the muted slow fashion aesthetic of the West—denim butterfly sleeves, glazed stoneware palayoks in place of terracotta, and an inabel weave in binakol print casually hung on top of white linen as the background sampayan. It was purposefully restrained, perhaps to present the Filipino identity outside the confines of moms with funny accents, plastic-covered couches, and uncles named Jun.

Filipinos who are native to the Philippines often tend to police the authentic “Filipinoness” of any Filipino American activity. I found myself falling into the same habit as I watched Sari-Sari do their thing. “It's so New York,” I told myself, after reading how Gabriella likened the Filipino Sari-Sari Store to a bodega. “That's not really what it's like.” As I drew on the imagery of tiny caged windows, I continued to think of shampoo sachets hung on window grills and televisions playing loud noontime shows. “Kulang,” I lamented. In my brief moment of cultural self-righteousness, I realized that I felt like Filipino culture was being taken out of context. In the case of the diaspora, that is really what is happening, and it is the context in which Gabriella's or Marielle's Filipinoness occurs. Though it vaguely looks like mine, the Filipino identity for Filipino Americans is not for me to define, as a Filipino living in the Philippines.

Marielle and Gabriella are acutely aware that many first-generation Filipino American creatives—who are trying to carve out space in industries where our culture is underrepresented—are talented and flying under the radar. Sari-Sari General Store evolving into a creative studio outfit was a natural progression to fully realize the dream of amplifying the varied and nuanced stories from creatives in the diaspora. The earliest of their work that I discovered—and perhaps their most straightforward expression of Filipino American culture—was a show on YouTube called “Drunk Tagalog” featuring two Filipinx presenters, JV Gonzales and Fraunchie. JV Gonzales is a PR practitioner from NYC whose firm focuses on Filipinx personalities. He also launched Mercado Vicente, a directory of Filipino creatives who work across different disciplines. Fraunchie is currently a Senior Designer at AT&T and also freelances as a photographer and content creator.

Watching the episode they were in, it appeared that there was a Sari-Sari Studio cinematic universe—a cast of frequent collaborators pushing for the same goal: to push Filipinx identity to the forefront of American culture, much like how their other Asian counterparts have done. Their first story, produced with a new team member, Mal Tayag, was a story called "Filipinx Is Beautiful." In the piece, Sari-Sari explored Filipinx beauty that challenged the Eurocentric ideals prized in both Filipino and American culture. Mal shares that they were inspired to do the shoot when she heard a comment from a Filipina former winner of Miss Universe, who said that the two most recent Filipina Miss Universe winners were crowned mainly for their whiteness.

It’s the pervasive latak of whiteness, as I prefer to call it—a kind of residual culture from a colonial past diluted by re-emerging consciousness of native history stifled by the Western ideals inherently valued in capitalism. This subconscious dislike of the nature of being Filipino is brought about by a cocktail of cultures that are not our own. While we have much of our own reckoning to do here at home, the clash of Eastern and Western ideals requires constant negotiation to appraise their values and form a new culture in the diaspora. “It's a lot of doing the work,” Mal says. “But also, in a lot of ways, there's a privilege to it,” Gabriella adds. She says that privilege isn’t a matter of her picking and choosing parts of either culture, but more of having the freedom to distance herself from being Filipino or American, and taking a more nuanced look at how her heritage and her lived experience work to form her Filipinx identity—a work in progress.

“Despite all of our similarities and the common experiences we have as first-generation Americans, we draw from really different realities that inform our culture and our work,” Gabriella says. While Sari-Sari's platform aims to empower and amplify all Filipinx and BIPOC makers, I think their approach to design is particular to the East Coast and, more precisely, is very New York. It’s their attention to graphic design, and typography applied thoughtfully—a take on the design aesthetic du jour: texturally minimal, Filipino words and images written in unconventional type combinations. For the sake of generalities, West Coast Filipino Americans seem to be more in-your-face about the fact that they are Filipino. In contrast, the East Coast feels more considered.

“[West Coast Filipino Americans] have a more direct line to the history,” Mal says. “Filipinos had been landing on the West Coast far earlier than when they were settling in the East Coast, and in conditions that may have had a stronger requirement to build community,” Gabriella says, adding that the East Coast isn't without its own history of the Filipino American diaspora. Still, the West Coast’s history is more in-depth and more woven into modern Western society. “On the West Coast, you can go to high school and take Tagalog as a second language subject, much like French and Spanish. You could go to universities and major in Filipino Studies, something you cannot yet do here in the northeast,” she says.

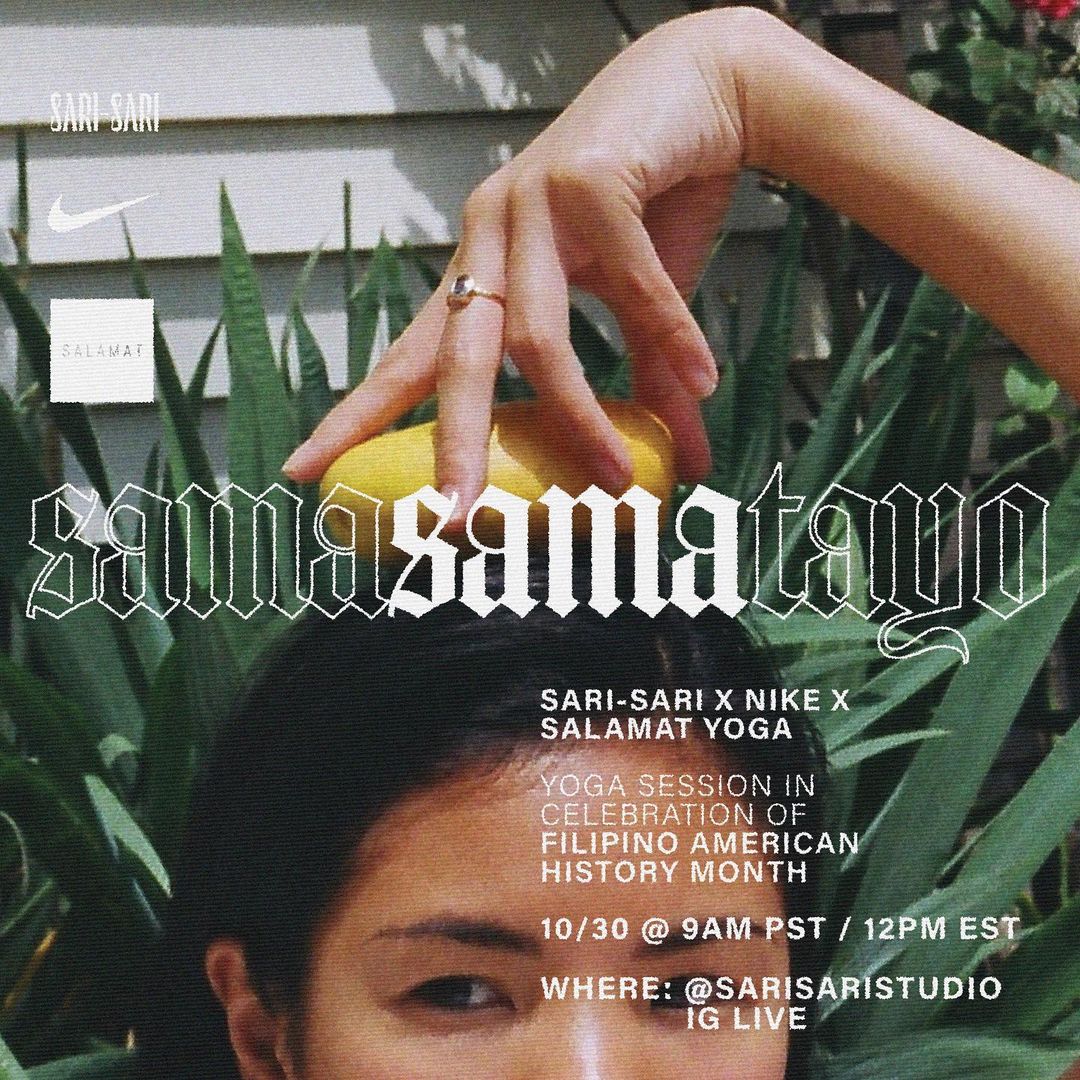

For Filipino American History Month, Sari-Sari Studio collaborated with Nike and Salamat Yoga on an online yoga session. It was a way for them to continue working with other like-minded Filipinx and BIPOC voices.

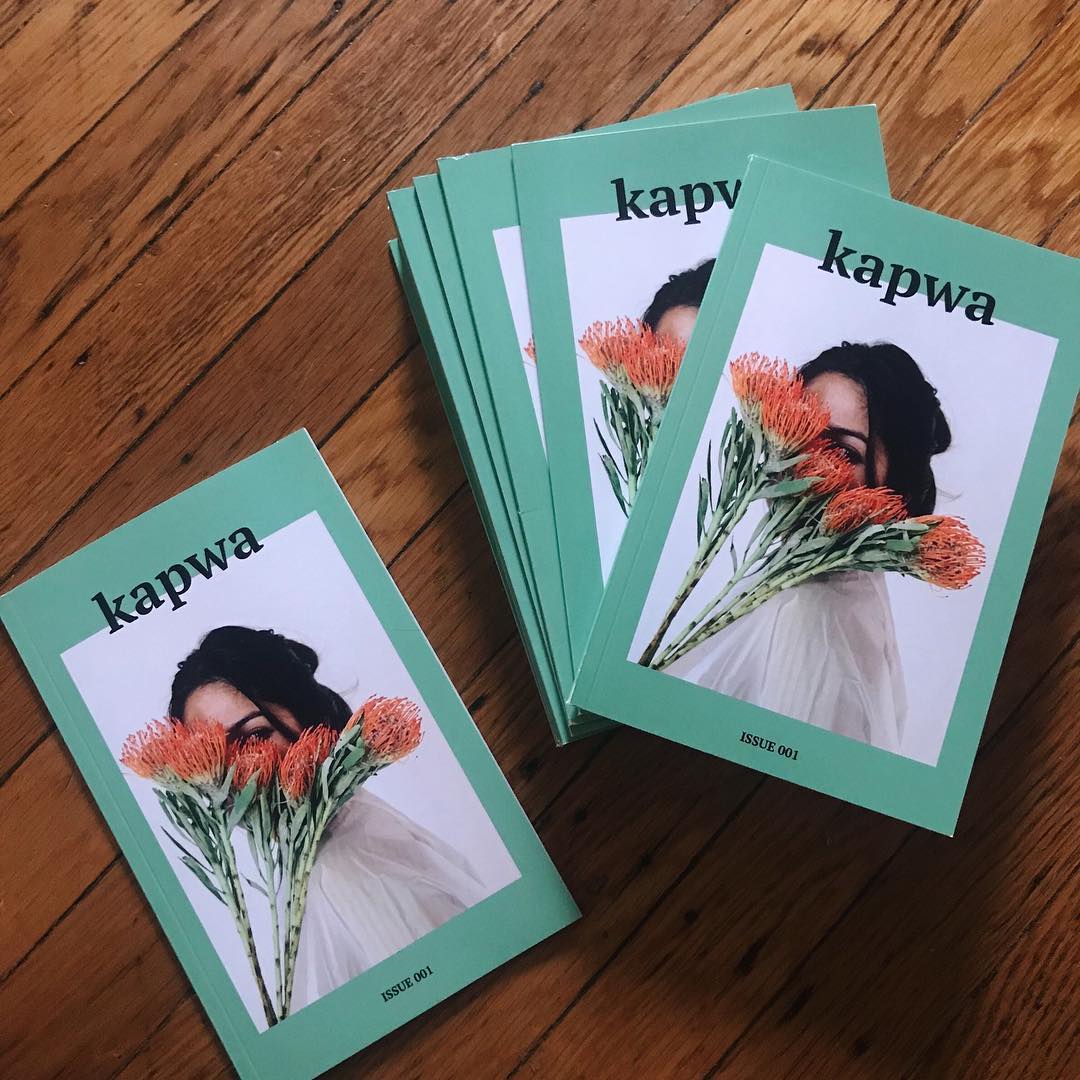

For Filipino American History Month, Sari-Sari Studio collaborated with Nike and Salamat Yoga on an online yoga session. It was a way for them to continue working with other like-minded Filipinx and BIPOC voices.Participation is central to Sari-Sari Studio, whether as a design studio or shop, or in their two new ventures, Sari-Sari Foods and Sari-Sari School. “Definitely, when we started Sari-Sari Studio, we were focused on events and activations as a direct way to interact with and get to know the community. Pre-pandemic we were doing a lot of pop-ups, dinners, art shows in NYC. Since March, we shifted our focus more on expanding our community digitally through our e-commerce store, zine, and collaborations while finding creative ways to come together to give back to our communities locally and globally,” says Marielle. I ask about their roles within Sari-Sari Studio and their designations for what each of them works on. Gabriella is the main product designer handling sustainability, design strategy, and illustration while also managing the vendors for the General Store. Marielle focuses on creative partnerships, photography, store curation, and content, and Mal handles most of the creative direction, graphic design, business strategy, and making sure all these are thoughtful and socially conscious. But at the end of the day, everything they do is a collaboration among them and the community. “From Sari-Sari General Store to the School, and to Sari-Sari Foods, our goal is to amplify these Filipinx stories and to continuously learn from the community as well,” Mal says.

Like most everyone, the pandemic and the inability to make face-to-face connections today are affected by local governments' strict guidelines on managing the spread of the virus. Similar to other brands, Sari-Sari took their activities online with the same goal of bringing together like-minded Filipinx and BIPOC creatives. “In celebration of Filipino American History Month, we did an online yoga session with Nike and Salamat Yoga, a Filipino American practitioner,” Gabriella says. “We did about one online event a week. Eventually, we burned out.”

In place of their usual events, Sari-Sari works to uplift other communities in their Filipino American periphery to spotlight different ways people are Filipinx. For example, Mal mentions, there is a group called IKAT Voices—IKAT standing for “Indigenous Knowledge, Art, and Truth”— whose mission is to amplify indigenous Filipinos' voices across America. This aspect of the work interests Mal in particular. In her work with Sari-Sari Studio, she takes a good look at how history affects heritage. “Through working with Indigenous women in Canada, and learning about colonization, I have a greater understanding of how heritage informs how we participate in culture,” she says.

Like most everyone, the pandemic and the inability to make face-to-face connections today are affected by local governments' strict guidelines on managing the spread of the virus. Similar to other brands, Sari-Sari took their activities online with the same goal of bringing together like-minded Filipinx and BIPOC creatives. “In celebration of Filipino American History Month, we did an online yoga session with Nike and Salamat Yoga, a Filipino American practitioner,” Gabriella says. “We did about one online event a week. Eventually, we burned out.”

In place of their usual events, Sari-Sari works to uplift other communities in their Filipino American periphery to spotlight different ways people are Filipinx. For example, Mal mentions, there is a group called IKAT Voices—IKAT standing for “Indigenous Knowledge, Art, and Truth”— whose mission is to amplify indigenous Filipinos' voices across America. This aspect of the work interests Mal in particular. In her work with Sari-Sari Studio, she takes a good look at how history affects heritage. “Through working with Indigenous women in Canada, and learning about colonization, I have a greater understanding of how heritage informs how we participate in culture,” she says.

“I grew up being so far removed from anything Filipino. As I got older, it was something that I was actively looking for, and I want Sari-Sari to be that space where people who feel the same way I did can find the community that reflects parts of their identity that isn't visible every day.”

At this point in the conversation, I ask, "Where does Sari-Sari see itself in five years?" I ask about big dreams. “I'd love to have a space one day where the community can gather," Gabriella says. She adds that it would be nice if Sari-Sari Studio could operate in different chapters in parts of the US or anywhere there are Filipinos in the diaspora in search of a community—at any capacity. “I grew up being so far-removed from anything Filipino. As I got older, it was something that I was actively looking for, and I want Sari-Sari to be that space where people who feel the same way I did can find the community that reflects parts of their identity that aren’t visible every day.”

A few months ago, I had seen that Sari-Sari designed a T-shirt to support the staff of a local Filipino restaurant during the pandemic. This was their first collaboration with a brand from the Philippines for people in the Philippines, and I ask if it was vital for them to regularly make more connections like these, whether with native or expatriate Filipinos. “If it happens, we'd love to. We all go to the Philippines pretty regularly, and we actively seek out new people to hang out with to see how different the new Philippines is from the Philippines our parents know,” says Gabriella.

I may have spoken for many Filipinos when I tell them that Pinoys look to their brothers and sisters in other countries to use their privilege to help with causes that affect the Philippines—in a way, to challenge Filipino Americans to deepen their connection with their motherland outside pride for jeepneys, balut, and Filipino exceptionalism. I describe a few people who have become problematic over time and ask if Sari-Sari are still comfortable with elevating these personalities as icons of Filipino culture. Mal quickly replies, “There is a way to be proud of achievements while holding these personalities accountable for any wrongdoing they commit. It also boils down to the lack of representation that we have as first and second-generation immigrants. That with any instance of displaying the Filipino identity in culture and media, we cling to it. The more Filipino identities we see represented, the easier it will be to identify with those who articulate their heritage outside the mold.” Gabriella painted a picture of the Roman Catholic immigrant who succeeds through hard work, good-old Filipino resilience, and their trademark sense of humor that smiles through the pain. It's undeniable that stories of overcoming struggle are part of the diaspora experience. But Sari-Sari Studio approaches their celebration of Filipino heritage by amplifying rich histories that present a narrative of what it means to be Filipino apart from hardship.

Wrapping up our conversation, Gabriella and I indulge each other in kwento. As we say in the Philippines, I was running out of English, and it was getting late for Gabriella, who was 12 hours behind. She asks about the article I’ll write about them, and I explain that my objective is to discover if, for Sari-Sari Studio, their Filipino identity is a guiding philosophy, aesthetic, or an outlet for their creativity. “It seems that because the work you do is always actively in progress, it's a combination of all three?” I ask. "I think one can't be without the other, especially when you're trying to really define identities that weren't so visible previously," she says.

There are parts of being Filipino American that inform their philosophy. A lot of it is in activism for better representation of the Filipinos in America, and in how they can use Sari-Sari as a platform to uplift underrepresented communities in the US. Their aesthetic aims to strike a balance between cultures—where explicit depictions of the Filipino experience are woven into Western schools of design to convey what their heritage means to them as individuals and as a community. And as for Filipino culture as an outlet, they hope that Sari-Sari Studio and its offshoots can provide a safe space for Filipino Americans to get to know each other and support collective efforts to advance what it means to be Filipino in America. It’s bayanihan; Sari-Sari Studio articulates what it means to be Filipino through their mission of building a community where Filipino and American cultures are symbiotic, working together in elevating a multitude of Filipino identities. ︎

A few months ago, I had seen that Sari-Sari designed a T-shirt to support the staff of a local Filipino restaurant during the pandemic. This was their first collaboration with a brand from the Philippines for people in the Philippines, and I ask if it was vital for them to regularly make more connections like these, whether with native or expatriate Filipinos. “If it happens, we'd love to. We all go to the Philippines pretty regularly, and we actively seek out new people to hang out with to see how different the new Philippines is from the Philippines our parents know,” says Gabriella.

I may have spoken for many Filipinos when I tell them that Pinoys look to their brothers and sisters in other countries to use their privilege to help with causes that affect the Philippines—in a way, to challenge Filipino Americans to deepen their connection with their motherland outside pride for jeepneys, balut, and Filipino exceptionalism. I describe a few people who have become problematic over time and ask if Sari-Sari are still comfortable with elevating these personalities as icons of Filipino culture. Mal quickly replies, “There is a way to be proud of achievements while holding these personalities accountable for any wrongdoing they commit. It also boils down to the lack of representation that we have as first and second-generation immigrants. That with any instance of displaying the Filipino identity in culture and media, we cling to it. The more Filipino identities we see represented, the easier it will be to identify with those who articulate their heritage outside the mold.” Gabriella painted a picture of the Roman Catholic immigrant who succeeds through hard work, good-old Filipino resilience, and their trademark sense of humor that smiles through the pain. It's undeniable that stories of overcoming struggle are part of the diaspora experience. But Sari-Sari Studio approaches their celebration of Filipino heritage by amplifying rich histories that present a narrative of what it means to be Filipino apart from hardship.

Wrapping up our conversation, Gabriella and I indulge each other in kwento. As we say in the Philippines, I was running out of English, and it was getting late for Gabriella, who was 12 hours behind. She asks about the article I’ll write about them, and I explain that my objective is to discover if, for Sari-Sari Studio, their Filipino identity is a guiding philosophy, aesthetic, or an outlet for their creativity. “It seems that because the work you do is always actively in progress, it's a combination of all three?” I ask. "I think one can't be without the other, especially when you're trying to really define identities that weren't so visible previously," she says.

There are parts of being Filipino American that inform their philosophy. A lot of it is in activism for better representation of the Filipinos in America, and in how they can use Sari-Sari as a platform to uplift underrepresented communities in the US. Their aesthetic aims to strike a balance between cultures—where explicit depictions of the Filipino experience are woven into Western schools of design to convey what their heritage means to them as individuals and as a community. And as for Filipino culture as an outlet, they hope that Sari-Sari Studio and its offshoots can provide a safe space for Filipino Americans to get to know each other and support collective efforts to advance what it means to be Filipino in America. It’s bayanihan; Sari-Sari Studio articulates what it means to be Filipino through their mission of building a community where Filipino and American cultures are symbiotic, working together in elevating a multitude of Filipino identities. ︎

Coco Quizon is a branding and marketing consultant for retail brands. Sometimes, she writes.